Elements of Abstraction - Elizabeth Gourlay in an Interview

Apr 27, 2016

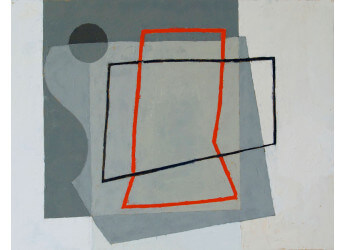

Elizabeth Gourlay considers her work a meditation on shapes and colors, sometimes comparing her studio practice to the process of composing music. Using a mixture of mediums ranging from oils to graphite to collage, Gourlay creates abstract compositions that reference an aesthetic vocabulary sublimely balanced between nature and geometry. A resident of Chester, Connecticut, Gourlay has work in four group exhibitions this month, in New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts. IdeelArt had a chance to chat with her about her practice, her exhibition calendar and her new body of work.

Elizabeth Gourlay Interview - Recent Exhibitions and Activities

IdeelArt: You’re having a busy month! This month you’re in four group shows in four different cities. When you find yourself in a time like this, when many different viewers are having the opportunity to encounter your work, do you still make time to stay active in the studio or do you prefer to be in the galleries interacting with those viewers and absorbing their reaction to your work?

Elizabeth Gourlay: This is the first time that I have had so much activity all at once. It is exciting but I am so used to giving individual shows my undivided attention, now I had to miss one opening to attend another. But once the artwork is delivered, time does become my own. While I am extremely eager to get into the studio after even a short period of activity that takes me away, I also enjoy the interaction that happens in the gallery, talking with fellow artists and friends during openings and other gallery events. Abstract art is a language, and talking with viewers, particularly artists and friends during events, builds up a sense of resilience in the new expressions we are finding.

IA: You have shows this month in idyllic, rural locations, such as The Tremaine Gallery in Lakeville, CT, as well as in densely populated urban centers, such as 1285 Avenue of the Americas Gallery, in Midtown Manhattan. What are the ways viewers in dramatically different environments have responded differently to your work?

E.G. In both cases, the audiences were visually sophisticated and seemed engaged and positive. In New York City, they generally seemed to be more vocal, asking questions and voicing opinions more readily. I think that the viewers in New York tended to go in closer to the pieces!

IA: What ways have conversations or other types of interactions with viewers affected the direction of your practice?

E.G. I try not to be influenced by viewers reactions, though, inevitably, if the response is positive towards a new direction that I am excited about in the work, then that does tend to influence me to continue exploring that path. It is always interesting to experience the difference of opinion and how and why people are drawn to different works.

Elizabeth Gourlay - Tantara 1, 2013. Monotype on paper. 40.6 x 38.1 cm.

Past and Present

IA: How is the work you’re making today different than the work you’ve made in the past?

E.G. My work, from about 1994, was very often grid-based and in a square format. It was built up in layers of washes and drawn lines. Around 2005, I began to play with much bolder geometric shape and saturated color. Since then, I have gone back and forth between bold, strong shape and color and work that is more delicate and muted, occasionally combining the two. The pieces often start in a similar way but can end very differently. Probably the largest change is the freedom that I allow myself in the process of creating.

IA: You sometimes reference meditation when discussing your work. Could you elaborate on what that word means in relation to your art? For example, do you consider the process of making the work to be meditative? Do you consider the finished product to be a potential meditative intermediary for viewers?

E.G. I do consider the process to be meditative. I do try not bringing too many ideas to the studio, perhaps a color idea or a shape idea. As I begin working, I let the inner eye, the unconscious mind, respond to the work and lead me to capture the illusive mental element that can be distant and yet so present. Usually, my best work happens when my thinking is uncluttered, when I am in tune with the work. Whether drawing directly or when layering washes, I enjoy the experience of letting the piece emerge. I cannot put it better than Paul Klee who said: “my hand is entirely the instrument of a more distant sphere.” I don’t work with any intention of creating something for the experience of another, yet I am open to their reaction and interpretation. I have had people who live with the work often say that looking at the work gives them peace, calm joy, or that the piece is grounding. So I am sure that considering the finished pieces as meditative intermediary is very valid, but I will let it be those that live with the pieces and those who are experts in mind and meditation make the best assessment. If an icon, or meditative intermediary, is an object that gives a calm joy, or a peace that is grounding, then yes I am often told that my pieces have those effects.

Elizabeth Gourlay - Kitha 4, 2014. Monotype on paper. 38.1 x 40.6 cm.

About the Process

IA: Wassily Kandinsky wrote about music and its ability to communicate emotion on an abstract level. You also make connections between music and your work. One connection you make is that your visual vocabulary of lines and colors might be interpreted to reference musical scales. What are some other ways that your process or your artworks share commonalities with musical composition?

EG: I am not consciously thinking about music or musical composition. Yet the number of people who make that connection to music is so large, there must be something to the analogy. I do listen to music, often, when I am working and I learned to play the piano as a child, so this may influence the work. I am “composing” in a way that may seem similar to musical composition, particularly in the process of playing with bars, lines and blocks of color. Shifting them around the picture plane is so similar to having notes and chords at different places around a score.

IA: Talk a little about your process, specifically the relationship you have with collage. For example, what are the ways that the process of layering paper in your work affects you differently than the process of painting?

EG: Most often, my painting process, whether on paper or linen, is very direct. Typically, I begin with drawing lines, followed by washes of color, followed by elements of shape. I try to surprise myself with a strong unexpected shape, or a color away from my usual palette. I move these around, trying to get a balance between color and form. This stage feels like a dance that is ongoing, where the formalism creeps in for a bit and where I push back against it. The decisions on whether or not to include the resulting bold intrusions is a kind of dynamic that can keep me engaged with a piece for weeks. The collage pieces start by playing with color, staining edges in ink and drawing lines onto Japanese paper and then cutting these into strips. I collage these onto the canvas or linen carefully but without a preconceived composition or structure in mind. As the piece develops, I do begin to analyze to allow the editor back into the room, to adjust color or shape until the piece feels right.

Featured Image: Elizabeth Gourlay in studio