An Interview with Ellen Priest

Aug 22, 2015

Ellen Priest has made her mark on the art world with her vibrant abstract collaged paintings for over thirty years. Influenced by Cezanne from the start of her career, and jazz since the 1990s, she has sought to capture the movements and intricate rhythms of a variety of jazz compositions in vividly coloured brushstrokes. IdeelArt had the opportunity to discuss her working process, while gaining insight into her influences and her passion for music along the way.

You mention you were greatly influenced by an exhibition entitled “Cezanne: The Late Works” featuring his late watercolours at the Museum of Modern Art. Does his style still influence and permeate your works?

Oh absolutely. It’s funny; it’s one of those insights that we have when we’re young. This one stuck for me. And I could tell at the time that this was something big. At the Philadelphia Museum of Art there’s a late Cezanne landscape that whenever I need to clear my head or gain inspiration, or figure something out, I go to see it. I’ll stand in front of that landscape until I figure it out. His late work has been a constant influence, and it’s been more than thirty years. I think what it is, is that he figured out a way to handle colours, and what many people don’t realise is that your choice of placement of a particular colour is essentially drawing. Cezanne had a way of understanding how objects in spaces hover. His way of thinking appears to match my own. Shapes appear, and then they dissolve. Then they re-appear and fade away again, which gives the illusion that the painting is breathing. He’s still just as magical for me as he was when I first saw the piece.

I feel lucky, honestly. I think it speaks to the strength and brilliance of his work. To me, he was as much of a watershed as Giotto with perspective and the way he handled figures in space. My hunch is that if I could jump forward 500 years, people would still be talking about Cezanne as a watershed. That abstract expressionism that fascinated me from early on is just as strong for me now. I feel lucky that I hit it and understood it early. I simply realised what was potent for me visually.

Can you tell us about your working process? Which materials and techniques do you use?

I use paper; all of my work is on paper. The paints that I use are flash and oil. Flash, as a vinyl-based water-soluble paint, takes pigments the way watercolour and gouache do. It doesn’t turn colours slightly brown the way acrylic does. It’s very compatible with the oils. Colour-wise, it’s a little bit different but they really work together within the space. I use pencil a lot as well. The papers go from being very heavy French watercolour paper, and two weights of Canson tracing vellum. One is very heavy called Opalux, the other is thinner and both are archival. I worked a lot over the last fifteen years with a couple in Boston, Jim and Joan Wright, who are both museum conservators, and they coached me in this process. Jim taught me how to use oil paint on this kind of paper without having a problem. I’ve been doing this for a long time now, and the work seems to be holding up fine; I haven’t had any difficulties with it. I also use MSA gel as my glue, and I don’t laminate the layer pieces - I spot-glue them - and I weight them down in order to get the gel to set. It takes about a week to dry.

You mention that you spend one to five years on a given series. How do you maintain your motivation and not burn out?

My process is quite a long one but it’s quite varied. It goes all the way from the brush studies, which are my first encounters with the sounds and the movement of the music. And the brush studies last maybe thirty seconds and it progresses all the way from that to slowly building these thick, layered pieces. I don’t have trouble because the process is one that has evolved over many years and it really works for me. It’s become a language that I’m very comfortable in, although it’s always a challenge. I think also that at a certain point, one just becomes professional, and it doesn’t matter how I feel on a given day. It’s time to go to work. I swim laps, have a smoothie, and get to work. I’ve learned that if my head isn’t in it, there are a variety of things I can do to work my way in. Usually I know the day before what I need to do for the next day. When I’m trying to figure out the colour relationships, I just have to sit there and look at it, and keep swapping out the colour swatches so I can see how they behave in the space. I’ll also have the music on. So the process itself at times carries me along when my mind and my heart are not necessarily there, but I need to get there. That discipline just comes with the years.

Ellen Priest - Jazz Cubano #2 front study, 2013. Gouache on paper. 106.68 x 106.68 cm.

How do you select your content and subject matter?

Subject matter and content are very different things. Content is the end result, or the feelings you experience when you’re looking at the piece. The subject matter is the jazz. Very few abstract artists have conscious subject matter. I found very early on that I could not keep my imagery fresh without going to outside subject matter. And I struggled with that for about ten years. It finally happened when I was listening to jazz. I was on my way to Vermont to go skiing and was listening to the local NPR station, and there was a piece by Michel Camilo who’s a Dominican jazz pianist. All of a sudden, I realized that the spaces that I was seeing in my head were spaces present in his music.

That was in 1990, and I’ve been working with jazz ever since. It’s conscious subject matter. And it took me several years to develop how I would develop imagery from it. De Kooning never saw himself as an abstract painter; he was constantly looking at figures and landscapes, occasionally still life. Joan Mitchell, who’s one of my other icons, had a very long career as an abstract expressionist painter and that’s really tough. She took her inspiration from landscape and poetry. She had a number of friends that were poets, one of whom was John Ashbury, and she “illustrated” his poems. De Kooning and Mitchell are among the few who have maintained this gestural expressionism style of painting throughout the length of their careers.

How do you navigate the art world?

Not very well. I’m one of those people where I know how to be a businessperson and I’m very professional, but I don’t feel that I’m very successful on that front. It’s an area that I’m still working very hard on. The biggest hurdle for me has been that from what I can tell, people who look at a lot of art always say to me that my work is something that you have to see in person. Not only that, the work is unique. No one else is looking at or using the materials this way. Uniqueness is an asset but it’s also a liability, because it’s hard for some people to have a way to relate to what they’re seeing because they’ve never seen anything like this.

You mention that your works are greatly influenced by the rhythms and intellectual rigor of jazz music. What are you currently listening to that fuels your work?

I actually listen ahead about a year or two before I start a new project. My projects can take anywhere from a year to five years, so if I’m going to work with a particular piece for that amount of time, I’d better like it! Otherwise I’d be in big trouble if it doesn’t stick with me. I’m just finishing this Jazz Cubano series, and I tackled that because I love Afro-Cuban jazz. The rhythms are so complex that I realized the only way I could figure them out is if I broke them down into the simplest pieces—one percussion sound at a time—and then built my way back up. This has been a really fun series. I’ll finish this by the end of the fall for sure, and then I’m getting started with a CD-length composition called The River by a Chicago-based pianist and composer named Ryan Cohan.

It’s a beautiful piece and it has eight sections that are very carefully written. Between each, there is an improvised piano section—that’s symbolically the river. He had a grant to travel to Africa, and Chamber Music America, who also funded Edward Simon’s Venezuelan Suite, which I worked on for five years, funded the composition. What Ryan has done is to take African rhythms along with everything else he’s been influenced by, and make it into something that was really his own. This is a beautifully digested and innovative piece of music. It’s very intelligent and has a great deal of emotional range. What I’m finding is that I’m often attracted to things both emotionally and intellectually. I’m really looking forward to The River. That I will begin in late fall, or most certainly before the end of the year.

Ellen Priest - Jazz: Edward Simonʼs Venezuelan Suite 16, 2008. Papers, oil, flashe, pencil, MSA gel. 106.68 x 106.68 cm.

Which of your art pieces are you most proud of why?

I think the pieces I’m the happiest with are in two different groups: one would be the last few pieces in the Venezuelan Suite series, because I was able to get a level of complexity and simplicity at the same time that I was very happy with. I was finally able to finally capture the speed of the music without it getting lost. I also thoroughly enjoyed the drawings in the Jazz Cubano series. They’re so stripped down, but they have a lot of bite. Those would be the two groups I would say I’m extremely proud of. As for a specific piece, I really couldn’t say.

How do you know when a work is finished?

I think there comes a point where I’m looking at a work, and at each stage I have to make that decision. When there’s nothing more I want to do, or when it feels anything more I'd do is too much, that’s when I know it's complete. I usually wait and look at it for a while. Sometimes I’ll know what to do immediately, but sometimes it takes a bit. If there’s an area that’s not moving I’ll try to figure out a way to get it moving. Often that means I have to tweak some other part of the painting. It might not necessarily be the spot itself; it might be some other component that may need to be changed. Generally, I sleep on it for a bit. I might think it’s done, but I’ll just wait. I have to make these decisions prior to gluing. When I trim the edges of the piece, sometimes I get a surprise—and it’s not always good. Now and then I’ll put something together and it’s not what I was expecting. Sometimes after trimming the pieces, the piece may be off balance and I can lose the piece because it no longer shows the range of emotion it once did.

What does having a physical space to make art in mean for your process, and how do you make your space work for you?

I have an old house, a three-story from the 1890s, or what we call a twin. I have three stories of North light and I’m on a corner. So I have tremendous amounts of light. I use the whole first floor for my studio except for my kitchen. On the second floor I have my office and living area, and on the third floor is where my gluing and storage room are. So I really have not only adequate, but also good space, and it’s made all the difference in the world. Having permanent ample space has been a godsend for my work. Being able to settle in and get it to work properly has been amazing. Sometimes I think I could use more space, but I have enough space!

Ellen Priest - Jazz Cubano #27: Arturo and Elio, Thinking Out Loud, 2016. Papers, oil, flashe, pencil, MSA gel. 81.23 x 81.23 cm.

What speaks to you when you see an abstract piece?

To me, abstraction (when it’s good) has clarity of thinking that really appeals to me. It can be colour, it can be black and white, it can be very full of imagery or it can be a single form floating in the field. But there’s just a quality of thinking that’s crisp. One of my favourite contemporary artists of all time is sculptor Martin Puryear. I once walked into a retrospective of his works at the MoMA, and it took my breath away. The same show was being presented in Washington D.C. and I rearranged my entire schedule to go and see it again. He’s brilliant; his work has such a purity of form and thinking. His work has references to vehicles, animals, boats. Abstraction can make references to the real world, and still be abstract. Your eyes use the same cues to get around in the world that they use to look at abstract art. Our eyes figure this out early on in life. We’re using those same tools to look at abstract art, but we aren’t aware of it. There’s something about abstraction that builds on our understanding of the world.

Are you involved in any upcoming shows or events? Where and when?

I’m in talks with Saint Peter’s Church in Manhattan, which is where I showed this past spring— I’m hoping to show another project there, which is about The River. Aside from that, I may have a local show here in Wilmington, Delaware this fall on the Jazz Cubano series.

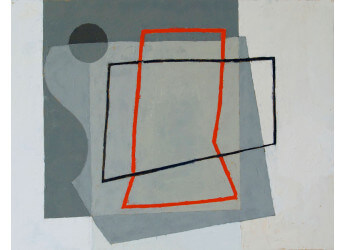

Featured image: Ellen Priest - Jazz: Thinking Out Loud, Reaching for Song 31, 2011. Papers, oil, flashe, pencil, MSA gel. 81.3 x 119.4 cm.