An Interview with Jeremy Annear

Jeremy Annear (b.1949) is a highly respected and successful Abstract artist based in Cornwall, England. His work is held by the Ionian Trust and The Royal Holloway Collection among others, and he has exhibited internationally in Canada, America, Germany, France and Holland; all locations which have had their own unique influence upon his work. His most recent exhibition at Lemon Street Gallery in Truro, a joint exhibition with his wife, Judy Buxton, served as somewhat of a homecoming for the artist, for whom the Cornish landscape is a great source of inspiration and contemplation. We spoke to Jeremy about the exhibition, his career and his view of Abstraction.

Can you tell us about the recent exhibition "Twofold: in Art and Life" at Lemon Street Gallery?

Lemon Street gallery is a leading gallery in Cornwall and it’s got a very good reputation nationally. It’s on three floors and Judy, my wife, was supposed to be having an exhibition throughout the gallery, but when she felt she didn’t want to occupy all three floors, we were persuaded by Louise Jones, the gallerist, to both show. I had a solo show in the basement of the gallery, which is a beautiful white cube space, very minimal, very contemporary, it suits my work very well. I had about 30 pieces in the show.

This was the first time you shared an exhibition with your wife, was there any interaction between your works?

No, our work is really very different and probably the secret of our successful painting partnership for thirty years. I have enormous respect for Judy as an expressive figurative painter and I think she’s got an incredible eye. I come from a very different place, from a Modernist tradition with my roots back to icon painting and then Italian Quattrocento painting, so I come through that kind of image into 20th century Modernism and people like Picasso and Paul Klee. There’s a very different sensibility to the work.

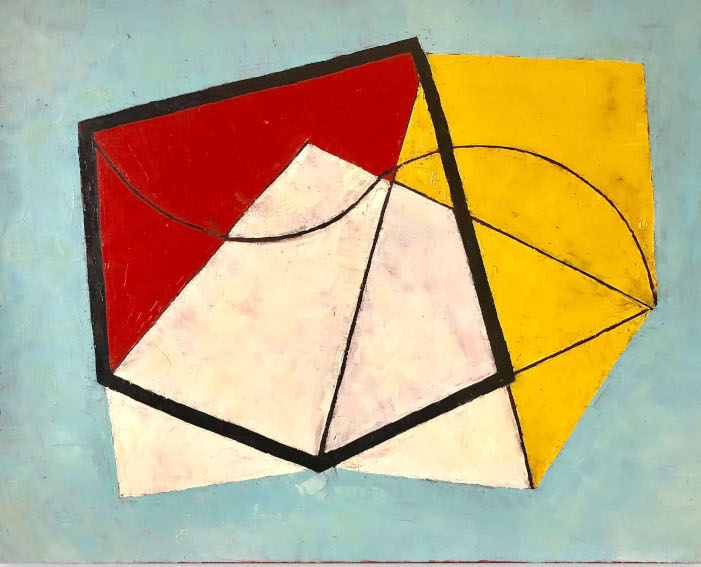

Jeremy Annear - Jazz-Line, 2016. Oil on canvas. 80 x 100 cm.

You describe a playful approach to painting: can you expand on this aspect of your practice?

I think there’s a deeper meaning to play than the generally understood sense of play – as in, if you’re playing then you’re not doing anything serious –, but I think there’s an approach, especially within creativity and thinking, where play is a light-handed approach and you recognise things like irony and metaphor and even aspects of mischief and prankishness, as in ‘the fool’ in literature. When I talk about play, I talk about it in that sense; it’s a place where you are released from a pedantic seriousness, but it has another sort of seriousness which is terribly productive.

Can you describe your experiences working and exhibiting in other countries?

I have always had a good relationship with showing work in Germany and Switzerland. I lived in Worpswede, Germany, for a year. It’s an absolutely amazing place which offers many artists, musicians and writers residences – mine was a very generous DAAD fellowship –, and it was very interesting to be in Germany, to work there and to encounter other artists, a lot of them from Eastern Europe, but a number of German artists too, and to feel that slightly overpowering sense in Germany of things having to be very well executed and very clear. The landscape reflected that because it is the reclaimed bog lands of northern Germany. It’s a lot of moorland which is reclaimed water so, although I was not near the sea, I felt as though I was sitting on the sea. It is peat bog and black dykes are cut in the landscape to tame it, creating well-ordered straight lines for miles, but at the same time the vegetation is beginning to take over and some of the order is being disordered by an unruly natural life. It’s a beautiful landscape but it took me a long time to get into it because I found it almost intimidating as it was so strict and rigid. Once I got into it I really enjoyed that. I’ve also worked extensively in Australia and in Spain and France, so I really like working in heat. I like the culture that is often around warm places: the ability to be a bit more physically free in a hot country, rather than in damp old Cornwall!

Jeremy Annear - Breaking Contour (Red Square) II, 2018. Oil on canvas. 100 x 80 cm.

Have all those different locations taken your work in different directions?

They’ve given me the ability to see work more broadly. In Germany I was very interested in the idea of collage, both philosophically and in making collage, and the idea of overlaying one concept or one idea against another idea; a layered approach to working. In Australia I was blown away by the toxic sense of a landscape that decays but renews itself, like it is tested by fire constantly. In France and, particularly, Spain, I loved the gutsy sense that the Spanish people have – it’s a hot bloody country Spain, it has that sense of slightly living in a dangerous place in terms of the politics and I like that edginess; I like the darkness that’s created by the extreme brightness: the sense of chiaroscuro. I like the reds that are created by the heat. Certain things in different countries have really had an impact on the way I work.

Why did you choose Abstraction?

The simple answer is that Abstraction chose me. The spiritual and philosophical and the big questions always attracted me even in my formative years. It has always existed in art and is to do with the why and how: the form and concept behind narrative and figuration.

Jeremy Annear - Sea Music., 2018. Oil on canvas. 60 x 40 cm.

Do you think abstract painting has had a Renaissance in recent years?

I don’t actually. I have quite strong feelings particularly about the British approach to Abstraction because I think, on the whole, the British find Abstraction very difficult. I think the British sensibility is to find narrative in things, so we have a very strong literary and music tradition in Britain but I feel that the art tradition hasn’t been so strong in terms of Abstraction. Somewhere like Germany is much more able to deal with abstract concepts and thinking. There’s a tendency, anecdotally speaking, in the art world for a photo-real, immaculately finished, perfection in art, which is not necessarily abstract but which has layers of meaning, a post-modern approach: a collage of both abstraction and figuration. I love pure abstraction although I haven’t always been a pure Abstractionist; I have probably gone through a stage of abstracting objects to what I now feel is a place of pure abstraction.

Do you ever re-work any pieces or revisit previous production?

I have come back to work and worked on it again. I never work on one piece at a time; I work on a body of work. I have a number of paintings that can be worked upon in the studio. I also think that my life as a painter is not about individual paintings, but it’s the search for the most essential statement that I can make, as simply and as minimally. My ideal painting would be a completely blank space, but a surface that was also compelling at the same time, but that’s like perfection which I know I will never attain! I suppose I am really searching for the essential of the language I speak; painting is my language and I try and find the best way of saying what I want to say as succinctly as possible.

Has there been a recent exhibition that has particularly stood out for you?

I recently saw a Louise Bourgeois exhibition in Malaga at the Picasso museum which was absolutely amazing and I really love her work. I also enjoyed a recent visit to the Miró museum in Barcelona. Braque, I’ve always regarded as my painting-father, there’s something which I find terribly compelling in his work. Looking at the life of Braque, his ups and downs of painting and the man he was: I find his life fascinating. I am a lover of Modernism, in all its guises, music architecture, and art. And I am a great lover of Brutalism in architecture and Minimalism in music.

Featured image: Jeremy Annear - Red Field V, 2012. Oil on canvas. 70 x 90 cm.