Interview With American Abstract Painter Dana Gordon

May 18, 2017

New paintings by Dana Gordon are on view at Sideshow Gallery in Brooklyn until 4 June 2017. We recently had a chance to catch up with Gordon and talk to him about this exciting new body of work.

IdealArt: In his catalogue essay for your current exhibition at Sideshow Gallery in Brooklyn, James Panero refers to your new body of work as “something different,” and advocates for the position that it represents a substantial change of direction for you. How do you respond to that assessment?

Dana Gordon: I agree, except that I don’t see it as a change of direction. I see it as the same direction, just the next developments; substantial new developments.

IA: Please share your thoughts about the relationship you had with improvisation while you were making these paintings.

DG: I see the whole process of painting as improvisation. I think of something to do, I try it out, and it works or it doesn’t. Then I again respond to what is there. I keep improvising until it feels finished. What I chose to do can be based more, or less, on the recent past of my work, the older past of my work, other art, other things of any sort that I have seen, thought, felt or experienced, and all of the above -- and often it is something that just pops into my mind and I try it out. Of course, there are always unconscious reasons for things that “just pop into” your mind. I try to let my unconscious guide my work, because there is much more in the unconscious than in the consciousness. This is done via visual response to the unconscious impetus, not via psychological or literary analysis. I think one has to practice this kind of response in order to get it naturally and fully, because the general course of education is to erase it from your abilities, though it is primary and primal. It is also a broad experience of visual art denied by much academic criticism. This is because these writers simply do not understand, or see, the visual and explain everything in art through literary, political, or literal approaches. There are of course writers who do understand the visual. It is hard to write about.

IA: The works in this show convey to me a sense that they emerged out of some kind of negotiation. What feelings of conflict and/or cooperation did you experience during the process of their creation?

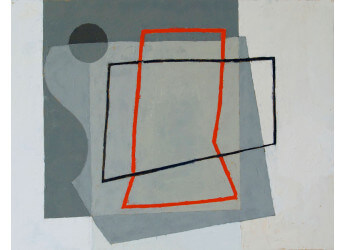

DG: Conflict or cooperation didn’t come into play -- at least not in my conscious experience. I suppose there is always a kind of negotiation – in the sense of: if I put this over here, and that over there, will it be better, or if I put it differently. I’m always weighing how well different things work. There is also an ultimate negotiation, I guess you could call it, when you have to decide between whether to keep a beautiful, amazing part of the picture, or sacrifice it in order to make the painting as a whole better. This is a frequent occurrence. Perhaps your question arises from the fact that all these paintings are divided in half vertically. And they apparently use several different kinds of abstract techniques. I found it interesting to have what could appear to be two paintings in a painting. And that I have made these two into one. And, really, three. There is each side and there is the whole. Perhaps there are really four: each side, the whole of the two sides, and the whole of the two sides and the one. Earlier in my career I made films that had parts that talked to each other, literally as well as figuratively and conceptually. There’s a film still of this in the catalog. James Panero referred in the catalog to “similar tensions, with a grid overlaying a free form design” and “triangles with hard edges balanced against wild lines.” As to using varied abstract techniques, I see them as all part of my inheritance as an artist. I can use or do what I want. There is a strong tendency in abstract art, especially since WWII, to reduce one’s work to one simple aspect of the visual, as reduced as possible. Why not use a lot of visual techniques instead of just one? Using varied technique and complex space is typical of the old masters, though it is hidden by the seamlessness of the depicted scene, the story.

Dana Gordon - Unruly Subjects, 2015-2017, 72 x 120 inches, oil and acrylic on canvas, © the artist

Dana Gordon - Unruly Subjects, 2015-2017, 72 x 120 inches, oil and acrylic on canvas, © the artist

IA: Is there a difference between conflict and cooperation?

DG: I’d say they are opposites. Of course, conflict resolution can result in cooperation. I don’t find that the areas and techniques in my new paintings conflict. I think that in each painting everything works together just fine. This doesn’t mean that all parts of a painting are the same.

IA: Please share your thoughts about your color choices for this body of work.

DG: Generally, almost exclusively, I don't use earth colors or black. Only what I consider “spectral” colors. The primaries, the secondaries; lighter and darker. And various versions of them available from different paint manufacturers. There really isn’t an infinite variety of these specific colors – the viewer can only perceive a relatively few different shades of any color (unless they are laid right next to each other, and even then, it’s not so many). Fortunately, the different manufacturing methods and different material sources provide variations. I use the primaries and secondaries mainly because their purity provides more intense color, i.e, more color. A redder red, a bluer blue, etc. These qualities also change depending on where you put the color in the picture, what shape it is and how big it is. My sense of color comes from many sources. First I am sure there is a native color sense that each person has that is different. Then, there is all that I have seen, both in nature and in art. In addition, I did study the Albers color system. The choice is from an unconscious interaction that tells me what color to use. All color carries, or can carry, powerful feeling and meaning.

IA: Do you feel that the color relationships you've expressed in these paintings are different than the color relationships you have expressed in previous bodies of work?

DG: No. Not to me. There are more painting techniques, though, so the same colors may appear different.

IA: In what ways did the process of making these paintings affect your relationship with gesture?

DG: Clearly there is stronger use of gesture in these than in those of the previous ten years. Gesture in the normal sense – the feeling of movement of the paint or from the way the paint was applied, and calligraphic line. Gesture (and as drawing) carries all kinds of meaning. I wanted to use more of it in these paintings. My work from earlier decades used broad gesture, too. In my mid-twenties I spent quite a bit of time studying Chinese landscape and zen painting, as I felt that these are a part of painting that a painter should digest. And around the mid-1970s, after a decade of working with shaped and three-dimensional canvases, and other related experiments, I “went back to the beginning,” put a chalk mark on a piece of black paper and redeveloped my work from there, exploring how marks become lines and make shapes. All kinds of lines and mark-making were explored over the years, The finest line becomes the outline for colored shapes.

Dana Gordon - Coming To, 2015-16, oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60 inches (Left) and Jacobs Ladder, 2015-2016, oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60 inches (Right), © the artist

Dana Gordon - Coming To, 2015-16, oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60 inches (Left) and Jacobs Ladder, 2015-2016, oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60 inches (Right), © the artist

IA: Please share the ways in which you perceive this body of work as an aesthetic statement, and the ways in which you perceive it as the beginning of a conversation with viewers.

DG: Any art is an aesthetic statement. I think that is the whole of it. Anything else in it – politics, literary ideas, etc. – is sentiment and reduces or obscures the art. The emotion in a Giotto, for example, comes from the artist’s aesthetic skill more than from his religious beliefs. His aesthetic skill allows him to embody his spirituality into the visual.

IA: In what capacity, if any, do you believe these works are in need of finishing by viewers?

DG: I do have a conversation with the painting as a viewer when I’m making it. I don’t think the painting needs to be finished by having viewers. It is finished when I’m done with it. I do hope the viewers have an engagement with the paintings, in a visual conversation, if you will. I’m glad if the paintings attain a life in the viewer’s mind. I hope this life is close to what I had in my mind and my feelings when I made the painting. I know it will be somewhat, or quite a bit, different.

IA: You have said in the past that you are inspired "to make abstract paintings that are as full, rich, complete and meaningful as the great master paintings of the past." In the context of that statement, how do you define the word "great?"

DG: What I meant in that statement is that I have a feeling that abstract painting has not, historically, attained the fullness of spirit, comprehensiveness of expression, and openness and complexity of space that the old master paintings had. I think Cezanne sensed this problem early on, as we can see in his famous statement, “But I wanted to make out of Impressionism something solid and lasting like the art of the museums.” I don’t think he accomplished what he meant by this, he accomplished something else. This isn’t to say that many of the great modern abstract masters didn't make deep and affecting art. Of course, they did. But it is confined to the adherence to doing just one thing, and to the exclusive need for flatness that pushes out toward the viewer. Yes there is some space in these paintings, but it is limited. I say this even though I revere Rothko, Pollock, et al as great artists. Miro got it, sometimes. Post war, I think Arshile Gorky came closest to what I have in mind, in much of his work of 1944 and after (and I’ve often thought he was the greatest of all his contemporaries – Pollock, de Kooning, et al). Hans Hofmann and Helen Frankenthaler get near it here and there. (I’m talking abstract here, not figurative in an abstract-ish style.)

IA: Could you offer some specific examples of the great master paintings of the past?

DG: Giotto, most essentially. Many of the Renaissance and Baroque masters: Masaccio, the Limbourgs, Titian, Georgione, Bosch, Velasquez, El Greco, etc., etc., all the way up to late (but not early) Goya.

IA: Have you arrived yet at the judgment phase about the work on view in this exhibition?

DG: I’m often in the judgment phase. About all the work I’ve ever done, from even before I start the painting, right up to the present second. There are plenty of times when I feel that I have put judgment out of my mind and proceed free of it when I am working. (Something like “getting rid of all the voices in your head,” a painter friend once said.) These times are very important. But whether they are really free of judgment, I am not so sure.

Featured image: Portrait of the artist, © IdeelArt

By Phillip Barcio