Interview with Claude Viallat

Jun 3, 2016

The French art history of the second half of the 20th century would be incomplete without mentioning a major figure in French and international art scene – Claude Viallat. This remarkable creator is one of the greatest French abstract artists in the last few decades. Although there were periods when he experimented with different styles and approaches, Claude Viallat remained loyal to his own visual language, often breaking the conventional rules and traditional painting techniques. Viallat is, in particular, praised for his famous method involving a single shape attached on canvas without any stretchers. Before the upcoming solo exhibition by Claude Viallat at Galerie Daniel Templon in Paris, IdeelArt, in collaboration with Art Media Agency, had the opportunity to spend an afternoon in the artist's studio in Nîmes, France, where he lives and works, and get an exclusive interview.

Claude Viallat - Essence and Negation

What is outstanding in Viallat’s career is the fact that he has always remained loyal to his own rules and norms, no matter how the others perceived them. Early in his career, Viallat was a member of Supports/Surfaces movement, where together with other artists he focused on materials and creative gestures, putting the subject itself behind. His experiments with color and texture led to the creation of a number of works he is best known for. In addition, Viallat painted on a variety of different surfaces, including recycled materials, umbrellas, various fabrics, woven or knotted rope. Claude Viallat, the great figure of contemporary abstract art, is still active, with a career spanning 50 years. The Parisian Galerie Templon is organizing an exhibition presenting a new historical perspective of works by this major French artist. The exhibition opens on June 4, and will be on view until July 23, 2016.

Your work plays a great deal on the repetition-difference pair. Repetition of gestures, procedures; difference in materials, colours…

I’d say that my work is first of all about the everyday nature of things. We are all people who constantly repeat the same gestures and we always obtain different situations from these gestures. Every day is a repetition of the same that results in different things

This is the principle behind my work: if you perform the same gestures on similar materials — and even more so on different materials—, every day you will obtain very different results. I don’t seek to invent something new: I let things come in such a way that newness is invented by itself.

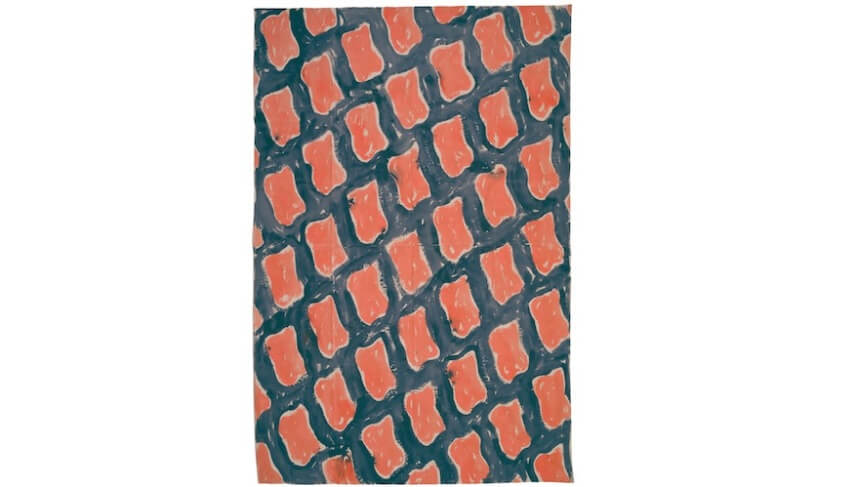

Every day, I live, I submit, I gather, I reflect, I salvage things — impressions, feelings, visions. I let all these nourish me. As I work on canvases that are neither coated nor pasted, materials are significant. Depending on the unctuousness of a colour, the material will take to it differently: it may absorb it, resist it, allow it to stand without soaking it in, or on the other hand, soak it in and diffuse it. I explore the way in which materials, fabrics —that may be velvets, tarpaulin, sheets — create an entirely different effect when dealing with colour.

You’re often described as a great colourist.

I accept the way in which colour shows itself, that’s all. A painter seeks tones in such a way as to match them. I place tones on a fabric, a material, and I accept the

Through these notions of acceptance, resignation, repetition of gesture, we can make a few parallels with Asian philosophies. Is this an influence for your work?

What interests me in philosophy is the effort involved in accepting not to intervene when something is happening. Accepting what happens, memorising it, analysing it afterwards – also seeing the possibilities if one had worked differently, the differences expressed by the same material. I aim to commit all this to memory, to forget it, and then to start again.

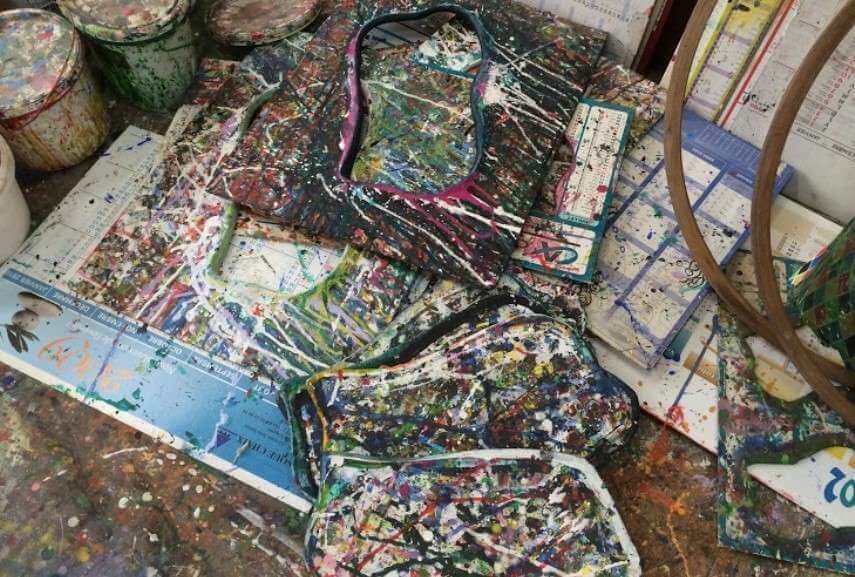

Claude Viallat in his studio

Claude Viallat in his studio

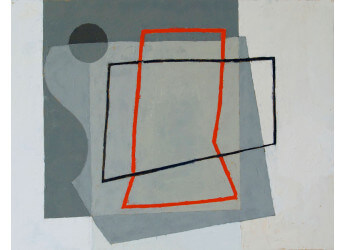

Claude Viallat - Sans titre n°39, 1985 , Acrylic on cover , 220 x 320 cm , 86 5/8 x 126 in

About Painting Style

Would this be your definition of painting?

There’s something of this in it. I belong to a generation who thought about the end of painting. In the 1950s, we often heard about the concept of the “last painting”. In short, it was necessary to invent a different way of

In my opinion, painting differently is a matter of questioning my profession. What does it consist of? Taking canvases, putting them on frames, pasting them on, dressing them then adding a range of colours to find the right tones. I’ve tried to stretch a raw canvas over a frame and to work with colours made up of hot gelatine with universal colouring. I’ve also used wood colouring, tried to dilute pigments with water, alcohol; I’ve used ephemeral colourings that offer no security, or acrylics.

The first monochromes still showed a desire to stretch canvas over a frame. But if stretching canvas over a frame made a painting, then it was necessary to dismantle this mechanism by putting the frame to one side, the canvas on the other — with the tension between these two elements making a new type of painting.

We found this with Supports/Surfaces. Dezeuze worked on the frame without a canvas; Saytour represented grids on raw canvases, that is, he put the image of the frame on the canvas; and I worked on canvas without frames, hence the painting’s deconstruction.

Retrospectively, how do you see this deconstruction of painting as a medium?

It was necessary. Young Americans still wonder about the deconstruction of painting but always bring the frame back to the foreground. It’s as if taking the canvas off the frame went against the history of art. For me, it’s a parallel history that has liberated painting, at least in one direction. If we look at the international scene, artists who work on unstretched canvas are rare. Americans have trouble getting rid of the frame.

Your work joins up with the idea, raised by Matisse, of paying interest to the painting’s basic object.

When Matisse painted, sometimes the white of the canvas appeared on the painting —which was traditionally considered a heresy. In my work, the fabric itself becomes the median support, and at the same time, the average colour, in other words, the standard according to which colour distribution is organised, its material. Everything reacts in relation to this standard. Depending on the quality of this median support, we obtain things that will form a relationship with it.

How do you situate yourself in relation to abstraction?

My painting is not so much a question of abstraction or figuration as a system consisting in repetition of the same form. If I change forms but not systems, then I change nothing. I become aware of the freedom I have by insisting on the same forms and by sensing the paradox of daily routine embodied by recurrence of the same form. Every day I construct infinitely different canvases, and this gives me extremely wide freedom.

In general, I don’t choose my fabrics, people bring them to me. I try to work with unlikely materials. It’s above all the material and its quality that make up the bulk of my work.

You travelled to the United States in the 1970s and you were touched by Amerindian art.

What feeds my work? The history of Western painting, of course, but also the history of all painting: Eastern, Far Eastern, Australian, American — and by American, I mean “indigenous”. All Indian ethnicities who have painted on tents or shields inspire me. Shield painting was usually done on round supports, and loaded with totem animals and the fruit of exploits— fox or wolf tails, scalps…. In short, everything that tells the warrior’s story. The Indian shield is not merely defensive, it is also a symbolic image of the warrior. The shield is round, generally made from a willow branch bent into a hoop and bound. In other words, the primary circle. This is the primary image of the round frame; just as the arch is the most extreme image of the canvas stretched on a frame —a string stretched on wood. These two objects are fundamental.

Similarly, prehistory was the era of the first pictorial representations. And what was the first pictorial representation? A human print; in other words, someone slipped, fell in mud, then put his hand on the wall of a cave. The act of slipping and dipping a hand in mud resulted in a loaded hand that then unloaded itself on the wall… As the mud dried, it created the image of the hand: this was the first portrait. The Other was represented by a part of himself, a trace, a print. After this first image, representation became more complex in that man created a countertype of his hand by spitting paint from his mouth over the hand. The right hand was a turned-over left hand. The act of spitting over the hand both widened and narrowed the perspective. Already, infinite possibilities underlay representation.

Your work seems to be related to reflection on essence, on origins.

That’s what I try to do. The circle, the hoop, the shield and the arch are primary elements. In history, there is knowledge about a certain number of gestures or systems that are both elementary and primary. For example the wedge that raises things up or blocks them, to stop something from rolling around. The plumb line is a rope and a stone, at the same time as it is a bullroarer —a musical instrument —, a way to weight something, to determine the vertical. All these elements are contained in this rope and this stone. There’s also the garrotte or the steelyard balance... These are universal, primary systems. What interests me, namely in sculpture, is reuse or the questioning of all these simple, universal systems.

Do your sculptures make up a universal grammar?

They are objects that are precarious, unfixed, that are left in their precariousness and offer no security. But the history of art is also the history of the art market, and these are not features that are traditionally valued by the market. They do not provide security.

The Studio of Claude Viallat

The Studio of Claude Viallat

Claude Viallat studio

Claude Viallat studio

About Art Market and Supports/Surfaces

Being so prolific, your work goes against the market. What is your relationship with the market?

All my work aims to demythologise art. Some elements traditionally characterise the market, such as the artist’s signature or rarity. I go against them. My work is prolific and I place as much importance on a painted thread as on a painted canvas. All painting elements constitute painting. A thread from a painting is a painting by the same virtue as the painting. I can sign a canvas but not a thread, so why should I sign the canvas if I can’t sign the thread?

Then there is the status of beautiful materials, a beautiful profession, as well as the security of materials and the sacralisation of the canvas. All my work goes against this as well. I take pleasure in working and I don’t see why I should deprive myself of this pleasure —and above all in the name of what. Perhaps my canvases suffer from it, but not me. The rest is a matter for the dealer, it doesn’t concern me.

Perhaps I’m pretentious. I never make mistakes because I seek nothing. I create, and I accept what I create. For me, all canvases hold the same importance.

Have you renounced all intentions to control?

The hardest thing is to accept not to master what we do from day to day. It’s a form of self-mastery to accept not to master what we do. The best way to change my work is not to know what I’m going to do, to force myself to discover, to analyse what I’ve just done and to predict what I might do. For me this means staying aware of all the possibilities that I’ve envisaged and then not needing them because the work gives its result by itself.

Supports/Surfaces has been exhumed in the United States. How do you feel about this?

That the work of Supports/Surfaces has arrived in the United States and that American painters are asking the same questions as we did at the time —but in their own way — seems entirely normal to me.

This is how things work. At the start of the 1970s, I showed a net at the Paris Biennale. It so happened that an American painter and a Japanese painter did the same thing, at the same time, even if we didn’t know one another. Through their own cultures, they arrived at this image on the basis of different logics. I find this fascinating.

But if painting changes, this doesn’t primarily affect the image —artists only see the image, this is our era’s blind spot. Modification of the image does not concern painting because it is painting itself that is interesting. The basic question is: “What is painting?”

Featured Image: Claude Viallat in his studio

Art Media Agency (AMA) participated in conducting this interview. AMA is an international news agency, focused on the art market. AMA produces over 300 articles each week, covering all aspects of the art world including galleries, auction houses, fairs, foundations, museums, artists, insurance, shipping, and cultural policy.

Images from Claude Viallat studio © IdeelArt