Ellsworth Kelly's Windows at Centre Pompidou

Feb 22, 2019

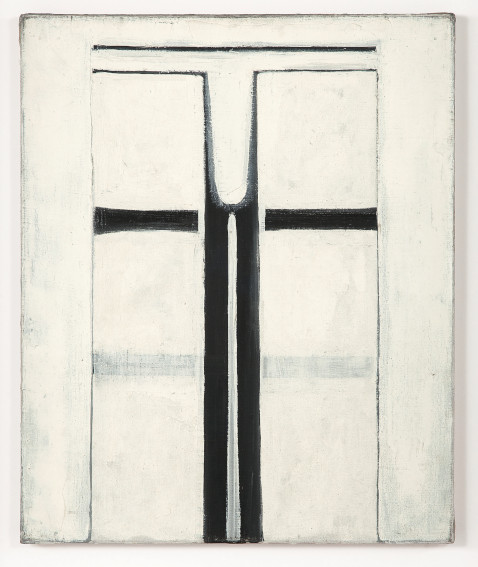

Right before he died in 2015, Ellsworth Kelly donated “Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris” (1949), to Centre Pompidou. Regarded as his masterpiece, the painting has confounded viewers, critics, and artists for 70 years. In honor of the anniversary of its creation, Centre Pompidou will present this essential work along with the five other Kelly “windows” in Ellsworth Kelly: Windows, from 27 February through 27 May 2019. When Kelly donated “Window” to the Pompidou, it was a homecoming. Kelly created it while living in Paris—not the first time he lived in the city; that was during its liberation from Nazi Germany in World War II, when Kelly served in the U.S. Army as a camouflage expert. He created “Window” when he returned to Paris long after the war. After returning to the United States and enrolling in art school, he got a chance in 1948 to move back to France with help from the recently enacted G.I. Bill, which offered assistance, including college tuition, to veterans. At that time, Kelly was a figurative painter, who, by his own admission, was not very familiar with abstract art. But neither figurative art nor abstract art, as he understood it, held his interest. He recalled in his essay “Notes” (1969) that he was far more interested in “object quality.” He admired the forms of things, like those “found in the vaulting of a cathedral or even a splatter of tar on the road.” In search of object quality, Kelly sketched leaves and pieces of fruit. He did not shade them or color them in; he simply traced the outline of their form. That, Kelly decided, was their truth. He explained, “Instead of making a picture that was an interpretation of a thing seen, or a picture of invented content, I found an object and “presented” it as itself alone.” “Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris” was the first “object” Kelly ever made. He saw it not as a representation of a window, nor an abstraction of a window, but as the concrete, objective manifestation of a specific form.

The Painting as Subject

As with many art historical breakthroughs, the conceptual ground Ellsworth Kelly seized with his “Windows” is subtle. His argment was that every form that is visible in the world is suitable as an object for an artist to create. This meanto to him that he no longer had to invent content, nor paint images, he could simply curate the form of an object from within the visible world, reduce it, and then recreate it exactly. He called his forms “already made” compositions. The name references the “Readymades” of Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp made his first Readymade in 1913—a sculpture consisting of an upside-down bicycle wheel attached to the seat of a stool. The concept, according to Duchamp, was that he could take ordinary manufactured objects and alter them in some way, thus making them his. His most famous Readymade was “Fountain” (1917), an upside-down urinal, signed with the name R. Mutt, and placed on a plinth.

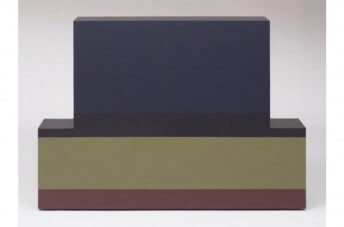

Ellsworth Kelly - Window I, 1949. Huile et plâtre sur Isorel. 64,8 x 53,3 x 3,80 cm. 87.63 x 76.20 x 8.89 cm. (cadre). Coll. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Helen and Charles Schwab and the Mimi Haas Collection, © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Ph. Jerry L. Thompson, courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio

Kelly was not editing manufactured objects. Rather, he was selecting already made forms from the total world of visible objects and distilling them down to their essential nature. If he had taken an actual window and signed his name to it, that would be a Readymade. By sketching a window, reducing the sketch to its most basic elements, and then recreating it precisely, he was doing something different. It was not a picture of a window, nor a sculpture of a window, nor was it an actual window. It was the object quality of a window made manifest. Kelly was eager to point out that people should not put any stock in the brush-marks, colors, surface qualities, or other aesthetic aspects of his “Windows.” He described his intentions thusly: “In my painting, the painting is the subject rather than the subject, the painting.”

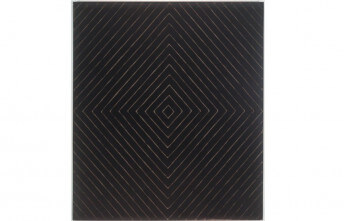

Ellsworth Kelly - Window II, 1949. Huile sur lin. 61 x 50,20 cm. 79,37 x 68,58 x 7,62 cm (cadre). Ellsworth Kelly Studio © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Ph. Hulya Kolabas, courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio

Splitting Heirs

Fittingly, all of the “Windows” Kelly made are opaque, making them useless as apertures, yet placing them in a long tradition of non-transparency, along with stained glass windows in churches, of portals that challenge our efforts to see. Donald Judd, in his essay “Specific Objects” (1965), certainly built upon the legacy Kelly started. Judd longed to free art from critical definitions such as sculpture and painting, and to expand his own work towards the creation of anonymous, universal forms that transcend simplistic analyses. Joseph Kosuth also built upon what Kelly did with his conceptual works, which place an object next to a photograph of the object next to a written description of the object. When a chair is placed next to a photo of the chair and a description of the chair, which one is the object? Which one is the art? Which one is the concept? Who decides? Does it matter?

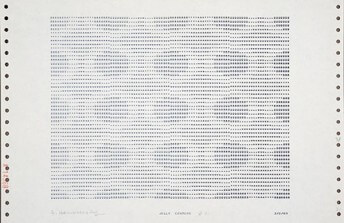

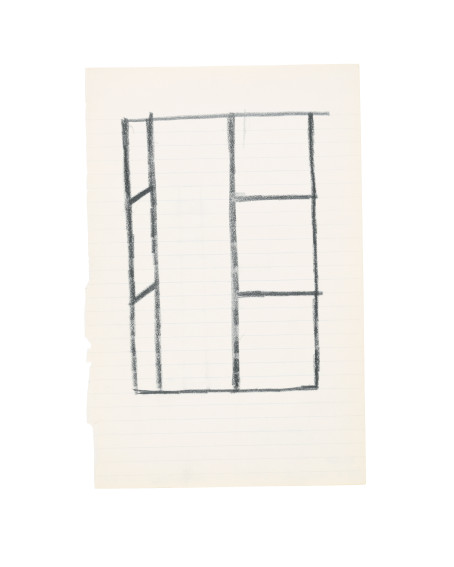

Ellsworth Kelly - Open Window, Hôtel de Bourgogne, 1949. Crayon sur papier. 19,70 x 13,30 cm. 40 x 32,38 x 4,44 cm (cadre). Ellsworth Kelly Studio © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Ph. courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio

The conceptual legacy to which Kelly contributed when he made his “Windows” irritates many people, because they see it as some kind of a joke. It seems obvious after all, that this painting is not a window; that this wheel attached to a stool is just a wheel attached to a stool, and not art; and that a chair is fundamentally different than a photograph of a chair. Happily, Kelly was quite open about what he was doing. He was anything but foolish. He wrote, “Making art has first of all to do with honesty. My first lesson was to see objectively, to erase all “meaning” of the thing seen. Then only could the real meaning of it be understood and felt.” Embedded within this statement I find some refuge, a reminder that all culture, and all history, is learned. We inherit context, but we are free to change that context, or break it down to its simplest form in order to understand it. His “Windows” may not be transparent, but they are statements of the belief Ellsworth Kelly had in our basic human right to develop, and then share, new ways of seeing and understanding the world.

Featured image: Ellsworth Kelly - Window VI, 1950. Huile sur toile et bois ;deux éléments joints. 66,40 x 159,70 cm. Ellsworth Kelly Studio. © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Ph. Hulya Kolabas, courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio