Hard-Edge Painting and the Aesthetics of Abstract Order

Would you like to climb inside of a hard-edge painting? Next time you’re in Las Vegas, go to the Cosmopolitan Hotel and Casino. At street level there’s a Starbuck’s coffee house. Walk inside of it and look up at the walls. You’ll notice bright patches of primary color painted on various surfaces and fixtures. On one of the walls you’ll see the signature of the man who painted these patches of color: the French artist and photographer Georges Rousse.

If you walk to the far end of the room you’ll see a spot marked on the floor inviting viewers to stand on it. From that one spot, and only from that spot, Rousse’s vision is fulfilled. Those painted surfaces are part of an illusion, a three-dimensional realization of a geometric abstract painting occupying architectural space.

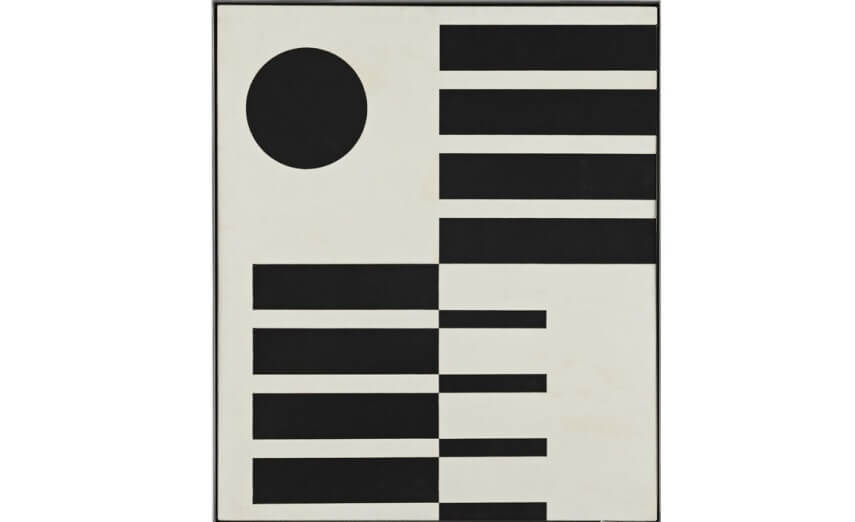

John McLaughlin - Untitled, 1951, Oil on Masonite, 23 ¾ × 27 ¾ in, Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter

What Is Hard-Edge Painting ?

The phrase hard-edge painting was coined in the late 1950s by Jules Langsner, an art writer for the Los Angeles Times newspaper. The term was a reference to an ancient tendency that was starting to reappear in a variety of different abstract art styles, but was particularly prevalent in California at the time. The tendency involved the use of geometric forms painted in bold, full colors clearly separated from each other with hard, solid edges. Two of the leading hard-edge painters to whom Langsner was referring when he coined the term were John McLaughlin and Helen Lundeberg.

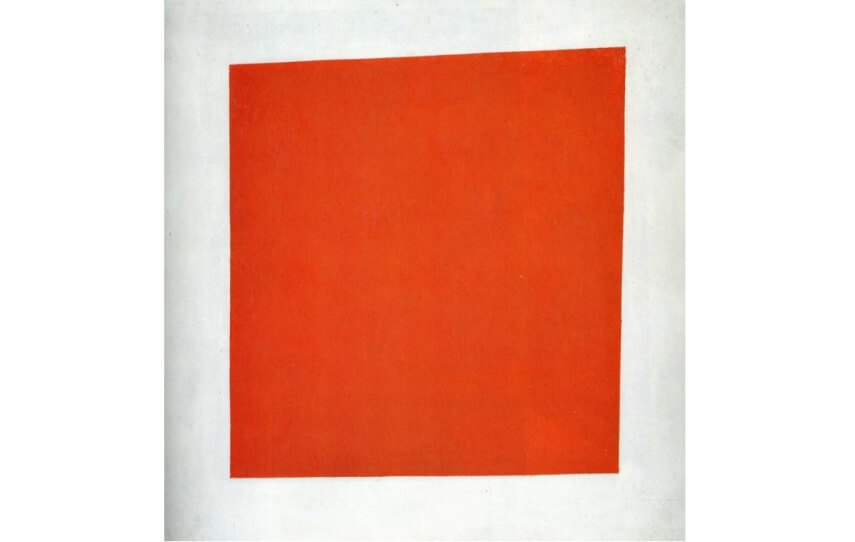

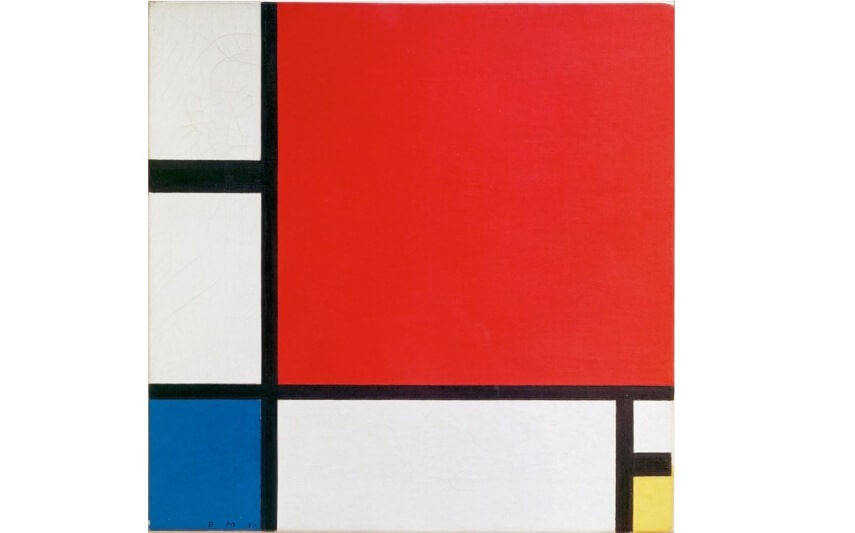

This type of painting had been done before for centuries, and had made its presence known in many different cultures. Even within the realm of Western Abstract art this tendency of working with bold colors, well-defined shapes and hard edges had popped up before, for example in the work of Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian.

The aesthetic of hard-edge painting had fallen out of fashion in the 1940s and 50s, in part thanks to the rise in popularity of the emotive, gestural work being done by the Abstract Expressionists. As it has come to be used in the contemporary sense, the term hard-edge painting refers not so much to any one particular style or movement in painting, but rather a tendency that Modern artists in many different styles have applied, and continue to apply, to their aesthetic.

Helen Lundeberg - Blue Planet, 1965, Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 in, The Marilynn and Carl Thoma Collection. © Feitelson Arts Foundation, courtesy Louis Stern Fine Arts

Kazimir Malevich - Red Square, 1915, Oil on Canvas, 21 × 21 in, Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

The Philosophy of Beauty

For many people, one of the most confounding elements of abstract art is that it doesn’t appeal to any objective definition of beauty. At least in the Western World, for centuries aesthetic beauty in painting was defined by natural and figurative subjects, such as portraiture and landscapes. Prior to the rise of abstraction, for an artwork to be considered aesthetically beautiful it was normally expected to replicate something considered beautiful in the objective world, such as an angel, or a historical figure, or a meadow.

When artists began dissecting the elements of what painting was they challenged the concept of what could be beautiful. Could the qualities of light on their own be considered beautiful? The Impressionists thought so. Could color on its own be considered aesthetically beautiful? The Orphists thought so. Many artists and art movements have since even challenged the notion of whether aesthetic beauty is even relevant. Should art have anything to do with beauty?

Piet Mondrian - Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow, 1930, Oil on canvas, 46 x 46 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Beauty of Order

Regardless of the philosophical games artists, critics and academicians play with each other the fact is that beauty does matter to viewers. Art viewers want to be in the presence of objects that help make them feel good. They want art to participate with them in their quest for satisfaction, whatever that happens to mean to them. Even if every art critic in the world considers a particular painting to be of immense historical importance, if no viewers want to be around it then its value rightly diminishes. The fundamental truth that human beings like to be around aesthetically pleasing things is something that many abstract art movements have wrestled with, and it’s something that hard-edged painting has helped many viewers confront.

There is beauty in order. There is beauty in rationality. There is beauty in color. There is beauty in line. There is beauty in something that’s pristine, unspoiled, clean and sensible. While many viewers even today have trouble at first seeing the beauty of Cubist works, or the abstract paintings of Wassily Kandinsky, it is undeniable that there is something attractive, or at least psychologically satisfying, about paintings that appeal to our desire for structure. The hard-edge geometric abstraction of Malevich’s Suprematist paintings and Mondrian’s De Stijl paintings is beautiful because it’s an aesthetic antidote to chaos.

Jackson Pollock - Blue Poles, or Number 11, 1952, Enamel and aluminium paint with glass on canvas, 83.5 in × 192.5 in, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

A Question of Taste

Of course none of this is to say that other types of abstract art aren’t beautiful. Beauty is a question of taste. For example, different viewers have a different capacity to unravel complexities. What looks like chaos to one set of eyes looks idyllic to another. Plainly the reason that action painters like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were as successful as they were is because so many viewers found their work accessible, relatable and beautiful. Though certainly some viewers consider a painting like Pollock’s Blue Poles to be a mess, far more viewers consider it to be an expression of human universalities and primal personal truth.

The reason hard-edge painting came back into style in the 1950s is perhaps because Abstract Expressionism was just so emotional. It had emerged after all out of the most violent, catastrophic and fearful times in the history of humanity, following World War II and the rise of atomic warfare. It makes sense that viewers who were confronting their own extinction day in and day out on the nightly news would eventually desire a return to something more conducive to a sense of inner calm, and some sense of order.

The hard-edge painting of the 1950s and 60s offered just that. It offered a return to the formal, classic qualities of geometric abstraction. Rather than looking at the horror of our psyches and the chaos inherent in our primal emotions, hard-edge abstraction offered us refuge in a contemplative, meditative space where form, color, line and surface were all that mattered. There, we could meditate on the basic building blocks of things and perhaps transform ourselves, at least temporarily, into something else.

Donald Judd - 15 untitled works in concrete, 1980-1984, Marfa, TX, The Chinati Foundation, Marfa

Minimalism and More

The return to formal, hard-edge aesthetics helped inspire a massive creative evolution in abstract art in the mid-20th Century. It inspired the rise of the Color Field painters, such as Kenneth Noland, who used flattened surfaces and large swaths of color to create meditative paintings through which viewers could experience transcendent sensations. It inspired Post-Painterly abstraction, a movement devoted to disguising the artist’s hand and highlighting formalist qualities such as color, line, form and surface. It also helped inspire the thinking of artists like Donald Judd and those associated with Minimalism, who achieved the height of unemotional expression by embracing aesthetic formalism.

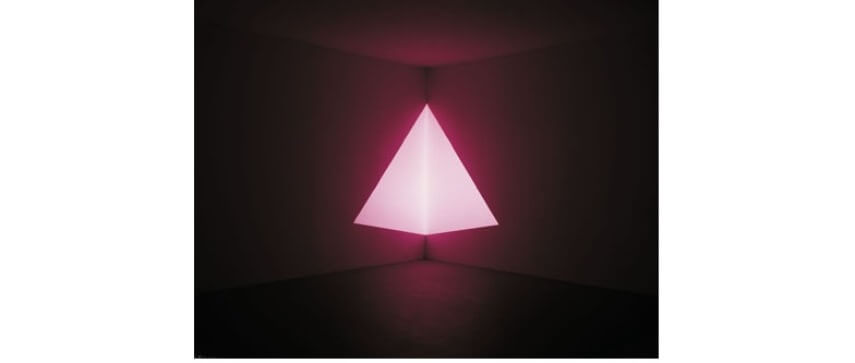

James Turrell - Raethro Pink (Corner Projection), 1968, © James Turrel

A Larger Legacy

Hard-edge painting also inspired the artists of the light and space movement. Anyone who has ever been inside an immersive work by James Turrell, or encountered one of his works that makes use of “apertures,” hard-edge holes cut in surfaces that allow light to come through, can clearly see the link between this work and hard-edge painting.

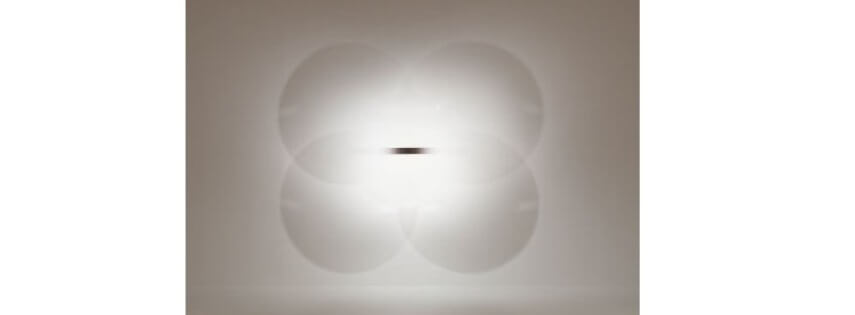

Even the installation artist James Irwin has been linked to the legacy of the hard-edge painters through his light works. The most famous examples are Irwin’s acrylic installations, in which a clear, curved, circular piece of acrylic is extended outward from a wall then hit with light, creating lines, geometric patterns and an interplay of light an shadow on the surrounding surface. These works extend the principles of hard-edge painting into three-dimensional space, allowing them to be inhabited by the viewer.

Robert Irwin - Untitled, 1969m Acrylic paint on cast acrylic, 137 cm. in diameter, © 2017 Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A Matter of Perspective

Whether hard-edge painting is more beautiful than more emotive styles of painting or vice-versa is purely a matter of opinion. And opinions change. Returning to that Starbucks in Las Vegas, we can see that’s the real essence of the message Georges Rousse may be trying to convey with his work. A hard-edge painting of a geometric shape can give us order and clarity. But not everyone finds bliss in order and clarity. Some of us like things to be haphazard. Some of us enjoy the chaos. The true beauty of Rousse’s hard-edge works is that with a simple step in any direction the edges soften and shift. They prove that perspective really is everything.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio