Fernand Leger, Between Abstraction and Cubism

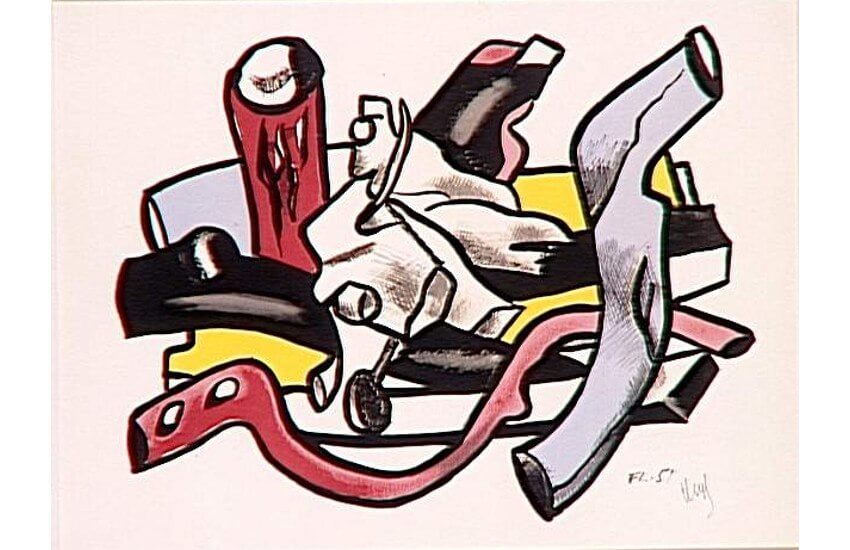

Because of the brightly colored, flat paintings of everyday objects he painted beginning in the 1930s, Fernand Léger is considered one of the forefathers of Pop Art. But Léger first became known for the unique variation of Cubism he created, dubbed Tubism for its use of cylindrical forms. When Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque first developed Cubism, they were exploring ways of showing the heightened reality of their subject matter. They divided their subjects into geometric planes, depicting multiple simultaneous perspectives to imply movement and the passage of time. But Léger saw a different type of potential hiding within the Cubist visual language. Rather than appreciating it for its academic treatment of subject matter, he valued its potential to objectify art, and to reduce it to its formal, plastic elements. In the hands of Léger, the aesthetics of Cubism became a democratizing force, one that freed artists to explore color, form and composition in new, unsentimental ways. This, he believed, was thoroughly modern. Using this approach as a starting point, Léger expanded the potentialities of abstract art by redirecting the focus from subject to object and plasticizing the elements of aesthetics, which laid the foundations for many important art movements to come.

Creating a Spectacle

Excitement was of paramount importance to Fernand Léger. He was born into a decidedly unexciting ranching family in rural Normandy in 1881. Realizing early that farm living was not for him, he studied architectural drawing and moved to Paris at the age of 19. There he found work as a draughtsman and also took whatever art classes he could find. But he found no inspiration in work or in school. He was filled with energy and angst, like many in his generation, heightened by watching the fabric of society rapidly change thanks to the spectacles of the industrial age.

In his essay The Spectacle, he elaborated on the impact he believed the modern industrial world of the early 20th Century had on the human eye. Describing the endless parade of visual stimuli modern society had created for the eye to admire, Léger wrote, “the artists who want to distract the crowd must undergo a continual renewal. It is a hard profession, the hardest profession.” The essential question for young Léger in turn of the century Paris was how exactly to affect such spectacular aesthetic phenomena that he could compete with the visual bombardment of his time.

Fernand Leger - Mechanical Compositions, 1918-1923 (Left) and Machine Element 1st State, 1924 (Right), © The Estate of Fernand Leger

Fernand Leger - Mechanical Compositions, 1918-1923 (Left) and Machine Element 1st State, 1924 (Right), © The Estate of Fernand Leger

Discovering Color

The way forward began to reveal itself to Léger when he saw a retrospective exhibition of the work of Cézanne in Paris at the 1907 Salon d'Automne. Léger realized that Cézanne used color differently than other artists. Rather than employing it in service of his pictures, Cézanne seemed to have made the pictures in the service of color. This was a breakthrough for Léger. It opened up for him the possibility that individual aesthetic components of art, such as color or form, could be worthy of exploration by themselves, without having to relate in any way to subject matter. It was the beginning of the idea for him that art could be objective and purely abstract, and could celebrate its own essential elements.

The French public at that time was resistant toward the idea of total abstraction. Most critics, gallerists, academicians and even artists considered subject matter vitally important to fine art. Picasso and Braques had made headway in changing minds with their Cubist style, but many viewers despised them for it, and regardless their images still relied heavily on subject matter. Isolating the geometric reduction Cubism employed, Léger simplified and abstracted the mechanized forms of the industrial world. He combined those abstracted geometric forms with vivid color, creating abstract compositions that evoked a combination of nature and machines. The resulting cylindrical aesthetic, which earned his style the name Tubism, resisted discernable narrative subject matter, creating an visual statement that was objective, modern, and most importantly, exciting.

/blogs/magazine/abstraction-and-geometry-by-ideelart-3

Fernand Leger - Dance, 1942 (Left) and Plungers II, 1941-1942 (Right), © The Estate of Fernand Leger

Fernand Leger - Dance, 1942 (Left) and Plungers II, 1941-1942 (Right), © The Estate of Fernand Leger

Stoic Plasticity

Just as Fernand Léger was becoming well known for his exciting new style, France entered World War I. Léger served in the French Army for two years on the front lines. In a story he later recalled about his wartime experiences, it is evident that Léger had a unique ability to interact with the world on an emotionally detached, purely objective level, a gift that helped him make an important Modernist discovery. The story goes that in the midst of a particular battle, Léger took notice of the spectacular way the sun was reflecting off the metal barrel of a nearby, mechanized gun. Despite the violence threatening his life in that moment, he noticed only the formal aesthetic beauty of that image of sunlight reflecting off industrial metal. He became entranced by colors, forms, and light. He divorced his mind from the narrative of his surroundings and reacted only to the objects in his field of vision. He took pleasure in their aesthetics without the baggage of sentimental attachment.

Of course by that time Léger had already established his ability to approach art from an unsentimental, objective perspective. But his experience in war was defining in how it caused him to realize how ordinary life was interconnected with art. It showed him the plasticity of the objective, ordinary world. He later wrote on this topic at length. In an essay titled The Street: Objects, Spectacles, he wrote about “the day when a woman’s head was considered an oval object,” and described “the direct accession of the object to decorative value.” He saw that just walking down an average street one could encounter endless aesthetic compositions equal to fine art just by admiring the objects on display, and by reducing people, animals, nature and industrial objects to their formal aesthetic components. He advocated that every visible thing can be reduced to an object and subsequently glorified in purely plastic, aesthetic terms. For that, he was a pioneer.

Fernand Leger - Branches (Logs), 1955, photo credits of Musee National Fernand Leger, Biot France, © The Estate of Fernand Leger

Fernand Leger - Branches (Logs), 1955, photo credits of Musee National Fernand Leger, Biot France, © The Estate of Fernand Leger

Featured image: Fernand Leger - The Great Tug, 1923, photo credits of Musee National Fernand Leger, Biot France, © The Estate of Fernand Leger

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio