The Abstract Figuration of Franz Marc

Franz Marc died at 36, but it is difficult to feel sorry for him. In his brief life he created a body of paintings that were so powerful that they are considered the height of German Expressionism. The most memorable of his works were his animal paintings, especially those containing his now iconic images of blue horses. One of the most famous, “Die grossen blauen Pferde (The Large Blue Horses)” (1911), is in the collection of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The painting shows three massive, bulbous blue horses lounging casually in an open wilderness of vivid reds, yellows, greens, blues and greens. It is simultaneously primitive and sophisticated. Its primitivism shows in the emotive ruggedness of the painterly brush marks and the haphazard blending of colors. Its sophistication shows in the extraordinary rendering of animal forms, and the perfect grasp of harmonious spatial relationships. The picture as a whole is clearly figurative—a picture of horses as the title implies. Yet there is so much else going on as well. The color relationships attain the highest emotional tension—the culmination of everything the Fauvists worked so hard to achieve. The picture plane is flattened—a nod to Art Nouveau—while simultaneously implying movement and depth—evoking both Divisionism and emergent Cubist philosophy. Finally, the picture is rife with symbolism. Marc developed a symbolic color theory which stated that blue is the color of masculinity, yellow the color of femininity, and red the color of primal nature. Sometimes the color theory implies hope and joy. Other times it is the color theory of an angry and radicalized person. That is the other reason it is hard to pity Marc for dying young. His death was a direct result of his own belief that the only way to achieve beauty was to hurl the world into the chaos of war.

Searching for Creativity

Marc was born in Munich, Germany, in 1880. When he enrolled at the Academy of Art at age 20, he was disappointed to find the teachers instructing students in the same ideas and techniques he had already learned from his father, an amateur painter. They were hooked on realism, while Marc was more interested in finding ways to express the underlying aspects of existence. He entered university the same year Sigmund Freud published his book “On Dreams.” Marc was fascinated by the underlying truth that existed in our fantasies. He started traveling back and forth between Paris and Munich in search of inspiration. In Paris, he met Jean Niestle, a realistic painter who focused almost exclusively on animals. Marc considered himself a Pantheist—someone who believes in one divine entity that encompasses all living things. He considered animals pure and peaceful, and humans impure and corrupt. From Niestle, he learned that animals could be depicted not just as representational forms in paintings, but as symbols.

Franz Marc - In the Rain, 1912. Oil on canvas. 81 x 106 cm. Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany

Marc next discovered the works of the Fauvists, a group of artists led by Henri Matisse who believed that color should be used to communicate the emotional state of the artist. Marc took from the Fauvists the liberty to create a personal color theory that applied only to his own work. He did not simply invent a color theory out of thin air. He took inspiration from the work of artists like Robert and Sonia Delaunay—the Orphic Cubists—who believed certain color relationships could create the appearance of vibrations. His choice of blue, yellow and red to symbolize masculinity, femininity and nature encompassed all of his various influences, and became perhaps the simplest and most all encompassing color theory of all time. It would be repeated later, in fact, by Piet Mondrian, who chose those same three colors along with white and black to depict everything in the universe.

Franz Marc - Monkey Frieze, 1911. Oil on canvas. 135.5 x 75.5 cm. Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Clamoring for Destruction

By 1911, Marc had fully developed his mature artistic vision. His work brought him back to Munich and into the orbit of one of the most influential artists of the 20th Century—Wassily Kandinsky. Together, Kandinsky and Marc formed the Blue Rider group, a.k.a. Der Blaue Reiter. The purpose of the group was to counterbalance another German Expressionist group of artists called Die Brücke, or The Bridge. Members of The Bridge adhered to an aesthetic style consisting of a sparse, clashing color palette, primitivistic lines and forms (a look chosen because none of the members had formal art training), and figurative imagery that depicted nudity, sexuality, and anything else that would invoke the youth of the modern world. The Blue Rider group did not have a specific aesthetic style to which they adhered. Instead, they shared a philosophy that formal elements like color contained spiritual values, so therefore content could be completely abstract and still convey meaning.

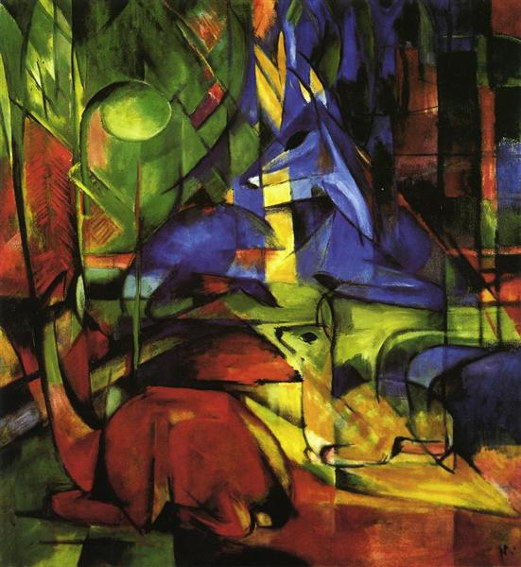

Franz Marc - Deer in the Forest II, 1914. Oil on canvas. 110 x 100.5 cm. Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany

Marc painted “Die grossen blauen Pferde (The Large Blue Horses)” at the beginning of his association with the Blue Rider group. It is a hopeful and confident painting. But as time went on, he become disillusioned with nature. He realized that people are animals, and the same impulses and desires he despised in humanity were also evident everywhere in nature. His work evolved to communicate this point of view. He adopted the Futurist technique of sharp angled lines, creating violent, chaotic looking images of animals in apocalyptic settings, epitomized by “The Tower of Blue Horses” (1913), which shows four horses, a reference to the Christian Apocalypse. One horse has a crescent moon on its chest, a symbol of war. Marc grew apart from Kandinsky, who remained committed to an idealist world view. His latest paintings, such as “Fighting Forms” (1914), show colors and forms exploding in total conflict. Along with fellow Blue Rider member August Macke, Marc enthusiastically volunteered for the German infantry in World War I. He had decided that only through war could nature be purified. He died in battle in 1916. His aesthetic legacy is one of intense emotion and beauty, blending figuration and abstraction in a way that forever influenced the trajectory of Modernist art. But his story is one of tragedy—of an artistic mind dragged by its own passions into the misery of war.

Featured image: Franz Marc - Fighting Forms, 1914. Oil on canvas. 91 x 131 cm. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Munich, Germany

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio