In The Spotlight - Georgia O'Keeffe's Gorgeous Watercolors

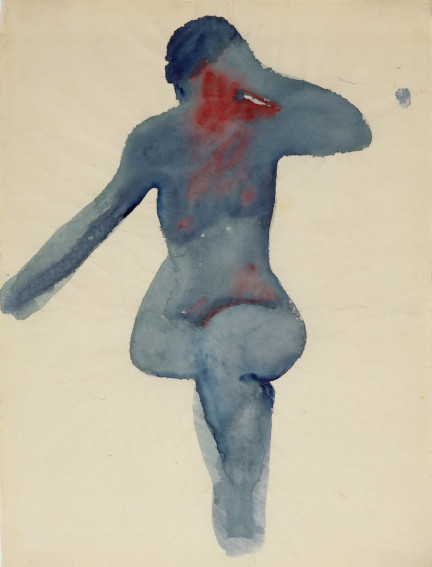

It may be hard to imagine a time when Georgia O’Keeffe was unsure of herself, or lacked confidence in her technique. Today, looking back at photographs of her knowing stare, her eyes glistening with wisdom and calm, it seems she must have always been certain that she would become a legend. But indeed there were many years early in her career when O’Keeffe was adrift in uncertainty, when she lacked a clear way forward, and was left searching for her authentic voice. One of those periods was between the years of 1912 and 1918. It was a time when she was coming back to the fine art world after leaving it behind; when she was struggling to break free from the traditions of the past and striving towards an understanding of Modernism. Most of the work O’Keeffe created during this time span shared a particular distinction: it was painted with watercolors. During a two-year span between 1916 and 1918, she completed 51 watercolor paintings. Forty-six of them are immortalized in full-size prints in a monograph published in 2016 by Radius Books, titled Georgia O'Keeffe: Watercolors 1916 – 1918. Named for an eponymous exhibition, the book catalogues well this rarely seen aspect of the O’Keeffe oeuvre. It also offers a glimpse into a pivotal time in the intellectual and aesthetic development of someone who eventually became the most beloved American painter of her generation. It shows a body of work that is nothing like the hard-edged, sophisticated, illustrious oil paintings for which O’Keeffe would later become known. Her early watercolors are experimental and open. They show an artist willing to err, and unafraid to stumble. In some instances, they even reveal glimpses of brilliance unsurpassed later in her career.

The Virginia Watercolors

When O’Keeffe picked up her watercolors in 1912, it was a homecoming of sorts. According to some reports, she had already decided that she would be an artist at age 10. Her first painting instructor used watercolors. But by age 18, O’Keeffe had adopted other mediums, like graphite drawing, which she excelled in at the Art institute of Chicago, and oil paints, which she mastered while studying at the Art Students League in New York. By 1908, however, at age 21, she had become disgusted by the smell of turpentine. Suffering from family financial devastation and illnesses, she walked away from the fine art field, seemingly for good, taking a job as a commercial illustrator. It was four years until she once again enrolled in painting classes, this time at the University of Virginia. Her medium of choice, during this time which became the most formative period of her life, was watercolors.

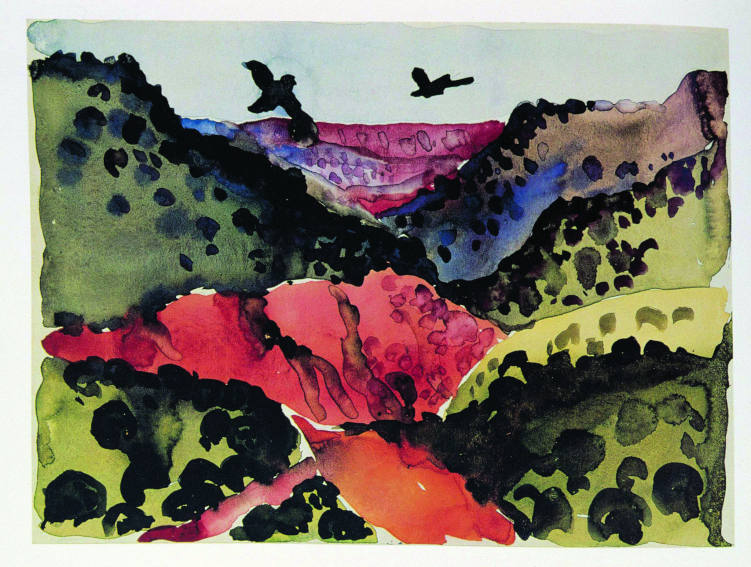

Georgia O’Keeffe-Canyon With Crows, 1917. Watercolor and graphite on paper. 8-3/4 inches by 12 inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Gift of the Burnett Foundation. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / The Burnett Foundation.

Her “Virginia watercolors” were recently exhibited at The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, in Unexpected O'Keeffe: The Virginia Watercolors and Later Paintings. They clearly show a painter moving away from the strict, mimetic tradition, instead embracing a language of form, line and hue that relates more to the inner world. Her mentor during this period was Arthur Wesley Dow, a revolutionary in the art education field. Dow was renowned for a book he had published in 1899 titled Composition: A Series of Exercises in Art Structure for the Use of Students and Teachers. In it, he championed art as a means of personal self-expression, and advised artists not to copy nature, but to instead use line, mass and color as a way of connecting with nature and expressing their individual feelings. O’Keeffe took a class with Dow in 1914. Not only are his ideas evident in her Virginia watercolors, but it was also Dow who inspired O’Keeffe to abandon paint for a while and just draw with charcoal. Those charcoal paintings were her first purely abstract works, and are famously what brought her work to the attention of New York gallerist Alfred Steiglitz, her future husband.

Georgia O’Keeffe-Nude Series VIII, 1917. Watercolor on paper. 18 inches by 13-1/2 inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Gift of the Burnett Foundation and the Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation. © Fire Dragon Color / Georgia O Keeffe Museum.

The Texas Watercolors

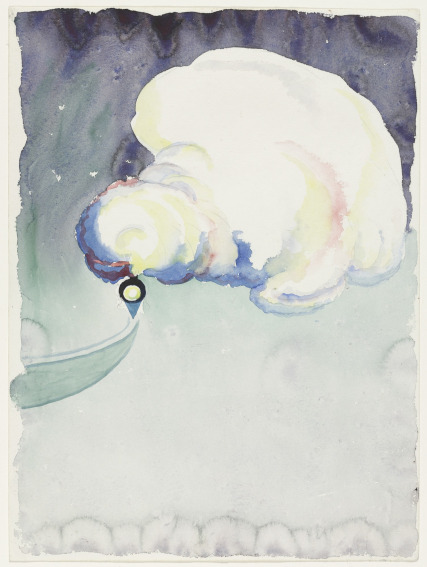

In 1916, O’Keeffe left Virginia and moved to Canyon, Texas, where she took a job as an art instructor. She was only just beginning to develop her individual voice as a painter. She taught in the daytime and then painted at home at night, intuitively constructing her compositions without sketching them out first. She wrote about translating the forms that she sees in her eyes, whether they related to anything in the real world or not. Many a mysterious, abstract form appears in her Texas watercolors. She also experimented with color relationships and a multitude of painterly techniques. Eventually, O’Keeffe destroyed many of her Texas watercolors, believing them to be an embarrassment later in life. One such watercolor, titled “Red and Green II” (1916), was logged in her journal as being destroyed, but somehow it avoided this fate. It was recently re-discovered and exhibited at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas, near where it was created.

Georgia O'Keeffe - Train at Night in the Desert, 1916. Watercolor and pencil on paper. 11 7/8 x 8 7/8" (30.3 x 22.5 cm). Acquired with matching funds from the Committee on Drawings and the National Endowment for the Arts. MoMA Collection. © 2019 The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The range of aesthetic variance in her Texas watercolors shows how O’Keeffe truly opened up as a painter during this time in her life. She opened herself to her inner voice and painted the parts of her world that spoke to her. She wrote about how when she moved to the Texas plains, the first thing that moved her was the light. She ended up capturing that light in a series of three watercolors titled “Light Coming on the Plains” (1917), which is considered one of her early masterpieces. These three watercolors embody perfect harmony between figuration and abstraction. Their blue hues project a cool and somber feeling, while the lines and forms convey a sense of pulsating radiation. The composition, meanwhile, adopts an egg-shape, suggesting new beginnings. In all of her surviving early watercolors, we see the earnestness that Steiglitz spoke of when he first saw the work of O’Keeffe. We see the sincerity of an artist who is searching for one true thing. We also see the playful whimsy that has come to define the heart of this artist, captured for eternity in its sublime and youthful genesis.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe- Evening Star No. VI, 1917. Watercolor on paper. 8-7/8 inches by 12 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Gift of the Burnett Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio