Observing Gerhard Richter's Abstract Painting

What is more truthful: a photograph or a feeling? Photographs are more objective, perhaps, while feelings may be more abstract. But both are real. Some painters in their search to convey truth devote themselves strictly to realism. Others see universal truths only in abstraction. For Gerhard Richter abstract painting and realistic painting both contain innumerable possibilities. The multi-disciplined oeuvre Richter has created over his 60+ year professional career contains roughly equal numbers of realistic and abstract works. His abstract paintings convey sentiments that are undeniably simple and true, while his realistic works create more questions than answers. Both communicate on different levels, yet both express the core ideas Richter has spent his life examining. Considered together, the body of work Richter has created is the manifestation of his stated goal as a painter: “to bring together in a living and viable way, the most different and the most contradictory elements in the greatest possible freedom.”

Unreal Realism

Gerhard Richter began his life in an age of totalitarian control. He was born into a German family in the city of Dresden in 1932. The Weimar Republic was collapsing and the Nazis were taking power. His father and uncles were all forced into military service in World War II. His uncles perished in battle. His aunt perished of starvation in a mental hospital as part of a Nazi eugenics experiment. His father survived the war, but the fact of his service caused him to lose his teaching career when the Soviets took control of East Germany.

Baffled and bewildered by his environment, Richter was not enthusiastic about life, and especially not about school. But that changed after the war ended. Thanks to the sudden availability of a flood of art and philosophy books when the soviets “liberated” the libraries of bourgeois mansions in his town, Richter developed an intrinsic desire to learn more about the world. He read everything he could get his hands on, and in 1951, at age 19, he enrolled at the art academy in Dresden. But sadly, he found that the only art education he could receive there was geared toward Soviet Realism. Though such art proclaimed to be realist, Richter knew from his youth there was nothing real about totalitarianism at all.

Gerhard Richter - Phantom Interceptors, 1964. Oil on canvas. 140 x 190 cm. Froehlich Collection, Stuttgart. © Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter - Phantom Interceptors, 1964. Oil on canvas. 140 x 190 cm. Froehlich Collection, Stuttgart. © Gerhard Richter

A Breakthrough in Düsseldorf

Despite the artist's distaste for the Soviet Realist style, Richter worked hard and was an exceptional student. But he also saw the writing on the wall that East Germany was only getting more restrictive each year. In 1961 he defected to West Germany, just months before construction began on the Berlin Wall. He settled in Düsseldorf, and even though he had already finished his art degree he enrolled as a student at the Düsseldorf art academy, which was attracting some of the most forward thinking artists of the time. It was the center of Informel Painting, as well as the local hub of the Fluxus movement thanks to Joseph Beuys who came aboard as a professor shortly after Richter enrolled. And his fellow students there included Blinky Palermo, Konrad Fischer and Sigmar Polke.

It was at the Düsseldorf academy that Gerhard Richter first began developing what would become his overarching ideas. He discovered the value of experimentation, the appeal of multi-disciplinary work, and the possibilities of abstraction. He also learned the value of humor, and the importance of creating work that is infused with energy and spirit. Perhaps most importantly, it was there that Richter developed his fascination with photography. Specifically he became focused on exploring whether the reality photography proposes is real at all, or is rather a partial, and manipulated falsity.

Gerhard Richter - Untitled, 1987. © Gerhard Richter (Left) / Gerhard Richter - Abstract Picture, 1994. © Gerhard Richter (Right)

Gerhard Richter - Untitled, 1987. © Gerhard Richter (Left) / Gerhard Richter - Abstract Picture, 1994. © Gerhard Richter (Right)

Blurred Photos

Richter first explored the nature of photographic reality in a series of what look like blurred copies of photographs. He based these paintings on actual photographs that he found in the press or in other photo archives. He painted the images in a simplified grey palette and then dragged a sponge or a squeegee across the surface of the painting to blur the image. The blurred photo paintings accomplished to goals. They elegantly expressed the underlying ethereality of the so-called objective world, idealized by the photograph. And they simultaneously re-exerted the value of painting as an expressive medium in a time when other forms were causing many to question its future relevance.

A third effect his blurred photograph paintings had was to nudge Richter closer to total abstraction. Encouraged by the formal elements of the work, such as the expressive capacity of the grey color palette and the visual impact of the horizontal marks made by the blurring effect, he began two new series of non-representational paintings that investigated the formal elements of color and line. The first was his Color Chart series, in which he divided canvases into defined grids, filling each square of the grids with a color. The second was a series of grey scale monochromes, which he called his Grey Paintings.

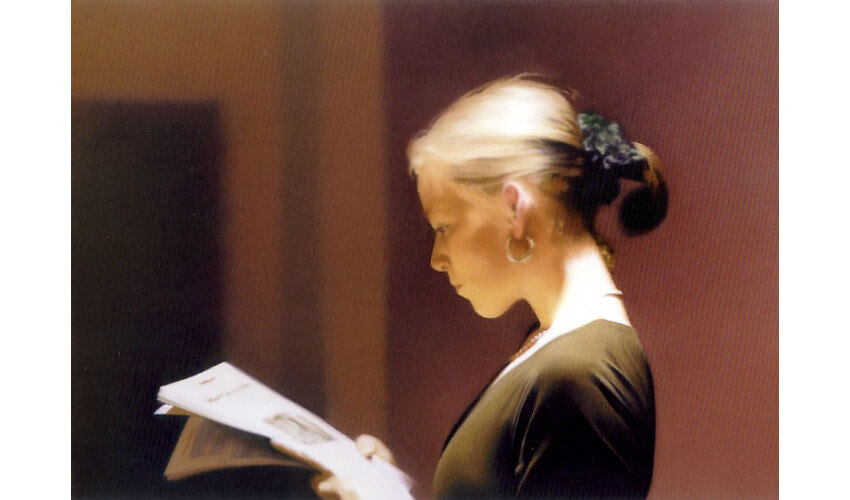

Gerhard Richter - Lesende (Reader), 1994. Oil on linen. 28 1/2 in. x 40 1/8 in. (72.39 cm x 101.92 cm). Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, USA. © Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter - Lesende (Reader), 1994. Oil on linen. 28 1/2 in. x 40 1/8 in. (72.39 cm x 101.92 cm). Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, USA. © Gerhard Richter

Redefining Abstraction

The next breakthrough for Richter came in a series of works he called Inpaintings. These works began as representational paintings, say, of a landscape or a city scene. He then painted over the representational image until it was completely obfuscated, and seemed to be totally abstract. As with the artist's earlier blurred photograph paintings, these works questioned the nature of reality and abstraction and examined where the line between the two actually is. Years later he revisited this concept yet again in his over-paintings, a series of photographs partially covered with abstract markings that examine the relative power of realism and abstraction as they occupy the same image.

These works deal in underlying and overlying truths. They raise questions about transparency and opacity. They invite us to see them not only as aesthetic objects, but also as objects of reflection. And those three concepts—transparency, opacity, and reflection—became the basis of the next major evolution for Richter in his work. He created a series of glass paned objects that gave off a subtle reflection of surrounding images. He then created a series of painted monochromatic mirrors, which offered over-painted reflections of reality in their surfaces.

Gerhard Richter - 180 Colors. © Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter - 180 Colors. © Gerhard Richter

/blogs/magazine/the-story-of-the-abstract-landscape-in-art

Uncertainty is Interesting

For the past three decades, Richter has devoted much his time back to painting. He has continued to explore color relationships in several new series of paintings. Some involve fields of color being swept into each other using his iconic squeegee or sponge technique. Others evoke biomorphic processes reminiscent of auroras or oil stains. Still others, like his recent line paintings, read like purely formal studies of geometry and repetition, and other elemental concerns.

It is up to us what the work means. Richter himself normally begins his process without knowing precisely what he is searching for, and often only knows what he has accomplished after his experiments have taken shape. It is in that unsure state of mind that gives him inspiration. The spirit of experimentation creates unexpected results, which to him are more exciting than preconceived notions. “You should have a measure of uncertainty or perplexity,” Richter has said. “It is more interesting to be insecure.”

Featured image: Gerhard Richter - Abstract Painting 780-1. © Gerhard Richter

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio