Inside the Reichstag, Gerhard Richter's Birkenau Tells of the Holocaust Horrors

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the re-opening of the Reichstag, the building that houses the Bundestag, or German federal parliament. It also marks the second anniversary of the arrival of “Birkenau” (2014) in that building. A four-part painting by German painter Gerhard Richter, “Birkenau” is named after the Birkenau concentration camp in Poland—part of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex, the largest extermination camp in Nazi Germany. The painting is the culmination of a decades-long struggle Richter undertook to craft an appropriate creative response to The Holocaust, when Nazis and their collaborators murdered more than 6 million Jews and hundreds of thousands of Roma, Poles, LGBTQ individuals, political prisoners and other minorities. The painting also represents a sort of personal closure for Richter, who was born on 9 February 1932, just one year and 18 days before the Reichstag Fire, the notorious arson that Nazi officials manipulated in order to consolidate power within the German government. Following the defeat of Germany in World War II, the Reichstag languished in disrepair for more than half a century, becoming a symbol of the shattered national confidence of the German people. In 1995, half a decade after German unification and the fall of the Berlin Wall, a four year restoration of the Reichstag was undertaken. In preparation for its re-opening, Richter was commissioned to create an artwork for the new Reichstag. He at first considered seizing that opportunity to make his long contemplated Holocaust work. Instead, in the spirit of Vergangenheitsbewältigung—the philosophical struggle for German culture to overcome the sins of its past—Richter created the hopeful “Schwarz, Rot, Gold (Black, Red, Gold)” (1999), a 204-meter tall, glass and enamel ode to the colors of the German flag, which now hangs one of two towering walls of the Reichstag foyer. Since its 2017 donation by the artist, Birkenau has occupied the other wall, directly across the foyer from “Schwarz, Rot, Gold (Black, Red, Gold),” a haunting embodiment of the aporetic complexity that often defines both politics and art.

Abstract Mnemonics

It has been said of “Birkenau” that Richter intends it to serve as a mnemonic device—something designed to help people remember something. Indeed, the biggest worry any compassionate person has when it comes to The Holocaust is that the world is going to forget what the Nazis did—either accidentally or as the result of intentional propaganda—and allow a similar tragedy to unfold once again. For this reason, countless artists have attempted to enlighten each new generation about this dark corner of history, either through painting, literature, film, photography, theater, song or documentary. But Richter is an abstract artist, and thus he was faced with the seemingly impossible task of creating an abstract mnemonic. How do you create an artwork that can remind us of a specific historical event without showing us the event you want us to remember? For that matter, how do you honor the gravity of death without showing it precisely as it is?

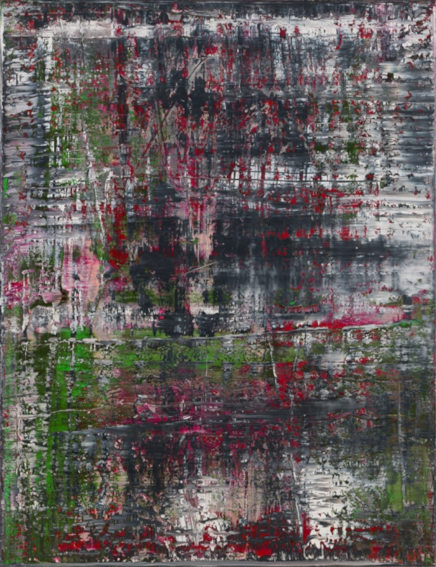

Gerhard Richter - Birkenau (937-2), 2014. Oil on canvas. 260 x 200 cm. Gerhard Richter Archive, Dresden, Germany. © Gerhard Richter

Richter found the answer to this perplexing question in the form of a series of photographs taken by members of the Sonderkommando, a group of Jewish prisoners tasked with burning the bodies of people who were murdered in the gas chambers of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Members of the resistance smuggled a camera into the camp, took pictures of bodies being burned then smuggled the film out in a toothpaste bottle. The photos served as evidence of this atrocity, and were memorialized by history. Richter, who has long collected ephemera of every kind that documents The Holocaust for a massive tome, which he calls the Atlas, felt these photographs of bodies being burned stood out as more powerful to him than anything else he had collected. They shined light on darkness, but showed only part of the story—people mundanely burning piles of human bodies like a weekend chore. So much more was left unsaid, but in the silence conclusions could nonetheless be made.

Gerhard Richter - Birkenau (937-3), 2014. Oil on canvas. 260 x 200 cm. Gerhard Richter Archive, Dresden, Germany. © Gerhard Richter

Revealing the Truth

The process Richter used to reveal the truth that he perceived in those photographs was one of trial and error. He first tried to paint the pictures as they were, but realized he was failing to express what was inexpressible by the images. He thus scraped off the paint and began applying layers of black, white and gray. He then added red and green—only the darkest red and green—the red evocative of blood, and the green reminiscent of the dark forests surrounding the death camp. Over time, the visceral darkness and literal weight of the paintings began to express the human cost of the photographs that inspired them. Within the layers hide so many of the human conditions that both led to The Holocaust and were caused by it: countless hours of tortuous, mundane labor; countless decisions made; inexpressible pain and emotional longing; hints of ego and a desire for greatness. Most expressive, perhaps, is the cover-up: the layers of paint themselves that actually cover up the original images Richter painted of what actually happened.

Gerhard Richter - Birkenau (937-4), 2014. Oil on canvas. 260 x 200 cm. Gerhard Richter Archive, Dresden, Germany. © Gerhard Richter

When Richter first exhibited “Birkenau,” he included not only the paintings, but also four reproductions, each divided into four quadrants symbolizing the four photographs that inspired the paintings. He also included more than 90 smaller segments of the paintings, arranged on the wall like a graph. Those smaller segments were then assembled into a book with no text, only pictures. It is as if he was exploring the infinite ways we can parse this history down into its components. We will never find the end of the small moments that led to the tragedy. We will never be able to tell the story of every individual who was affected by the events. Each component part is as beautiful and horrible as the big picture. Now that the painting resides permanently in the Reichstag across from a monumental representation of the German flag, we see the power of this epic journey into abstraction confronting the power of concrete symbolism. “Birkenau” is a reminder that history is more informed by such aesthetic matters than we realize.

Featured image: Gerhard Richter - Birkenau (937-1), 2014. Oil on canvas. 260 x 200 cm. Gerhard Richter Archive, Dresden, Germany. © Gerhard Richter

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio