Can We Find an Abstract Element in German Expressionist Art ?

Dark. Anxious. Frightening. Primitive. Crude. These are some of the words people use to describe German Expressionist art. For a visual reference of what those people mean, picture The Scream, the famous painting recreated multiple times by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch starting in 1893. That distorted, emotive, horrifically beautiful image embodies the many reasons why Munch was a primary inspiration for German Expressionist painters. So who were these artists, and what led them to develop of such a foreboding aesthetic? Maybe a more interesting question would be whether their aesthetic is actually as foreboding as it seems. Many people find the paintings of the German Expressionists to be haunting and evocative. Some even consider them to be revealing about the human spirit. Perhaps there are abstract elements in German Expressionist art, which, if we could interact with them, could lead us toward a deeper understanding of the meaning of these works. Few art movements have been as influential as Expressionism, the tendencies of which have repeatedly resurfaced in other movements throughout the modern history of art. If we can expand our understanding of the nuances and origins of this fascinating movement, we may also better understand Abstract Expressionism, Neo-Expressionism and certain current developments in contemporary art. We may even be able to learn something essential about ourselves.

So Very Romantic

German Expressionism was a 20th Century art movement, dating from about 1905 to 1920. But to understand its roots we have to look a little farther back. Many of the most profound changes in the history of Western art began in the middle of the 19th Century. The reason can be summed up in two words: Industrial Revolution. Prior to about 1760, most people in the Western world either lived a rural or an artisan life. They either worked the land or a non-mechanized trade. But during a 90-year span between roughly 1760 and 1850, that longstanding reality of life changed dramatically thanks to the rapid advancement of technology and machines.

By the mid-1800s, changes in chemical and manufacturing processes had rendered most of the agricultural and artisan work force obsolete. But urban industrial activity was increasing exponentially. To a degree never before seen, the population shifted from the country to the city, and along with that, the lifestyle of the typical human changed in radical ways. There were benefits, like clean water and affordable food and clothing, but also challenges, like pollution and overcrowding. Most disruptive was the self-centeredness of urbanity, which changed the way average humans related to each other.

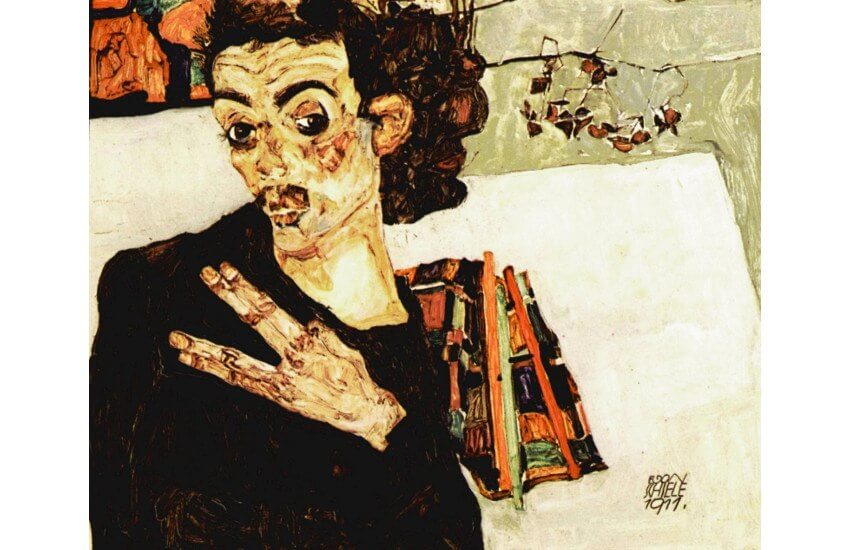

Egon Schiele - Self-Portrait with Black Vase and Spread Fingers, 1911, 34 x 27.5 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Egon Schiele - Self-Portrait with Black Vase and Spread Fingers, 1911, 34 x 27.5 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Artistic Impressions

The first artistic movement to come out of the Industrial Revolution was Romanticism. It emerged as those tens of millions of new urbanites realized that they longed for the bucolic, agrarian ways of their ancestors. Romantic artists portrayed the beauty of the natural world and the elegance of times gone by. After the Romantics came the Impressionists. These artists also focused on somewhat idyllic subject matter, but stylistically they took bold steps toward what would eventually become abstraction. Rather than painting precisely realistic images, they used new techniques and exaggerated their color palettes in order to beautifully and masterfully convey the impression of their subjects, with a particular emphasis on capturing the qualities of light.

But by the turn of the Century, yet another generation of artists was emerging, one that had no connection to the agrarian past and no desire to continue with existing aesthetic traditions. These were the children of the children of the Industrial Revolution. They were completely alienated from whatever idealistic world the Impressionists, let alone the Romantics, were endeavoring to represent. These artists were full of angst. Their paintings did not portray the objective outer world. Rather, they expressed the subjective inner world of emotions and life experiences.

Oskar Kokoschka - The Bride of the Wind, 1913 - 1914, Oil on canvas, 181 cm × 220 cm (71 in × 87 in), Kunstmuseum Basel

The German Expressionists

Those subjective life experiences were dominated by anxiety, fear, detachment from nature and alienation from other human beings. Since this experience was ubiquitous throughout the industrialized world, various versions of the Expressionist tendency manifested in different countries, all around the same time. Nonetheless, when most historians refer to Expressionism they first mean German Expressionism, since the artists who established most of the important aesthetic trends of the movement lived or worked in Germany at the height of the period.

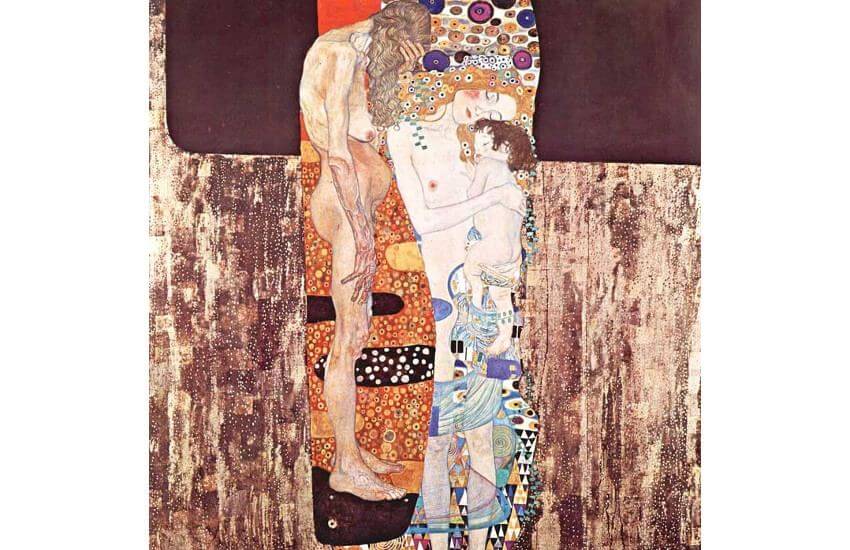

When looking for abstract tendencies in the work of those German Expressionists, it helps to analyze the two painters who influenced them the most. The first, as we mentioned earlier, was Edvard Munch. His lush, dark, dramatic and highly evocative style of painting captured the alienated sensibility of urban life at the turn of the century. His exaggerated gestures and extreme color palette incited emotion in viewers and connected them to the feelings of the painter. Gustav Klimt was the other painter who inspired the Expressionists, but he did so in a different sort of way. Klimt was influenced by the Symbolists. He used mythic, nightmarish figures in his work, and incorporated darkly symbolic imagery. His canvases contained large fields of abstracted imagery, and the figurative elements were grossly distorted to maximize drama and emotion.

Gustav Klimt - The Three Ages of Woman, 1905, Oil on canvas, 1.8m x 1.8m, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome, Italy

Gustav Klimt - The Three Ages of Woman, 1905, Oil on canvas, 1.8m x 1.8m, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome, Italy

The Bridge

Two main schools of German Expressionism eventually emerged, and they reflected the varying influences of Munch and Klimt. The first was a group of four aspiring painters, Ernst Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Fritz Bleyl, who called themselves The Bridge. Their name was inspired by a quote from the book Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, by Friedrich Nietzsche, which reads, “What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end.”

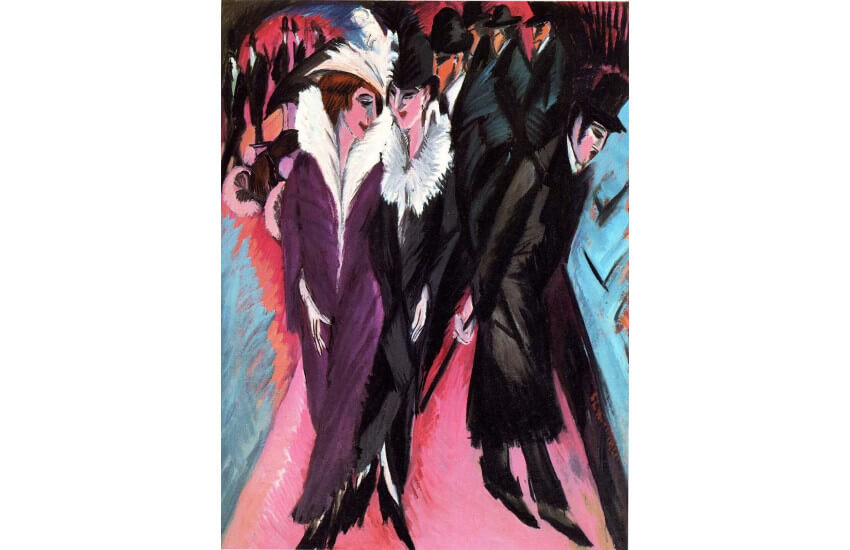

Distorted figuration and extreme color palettes united The Bridge artists; direct influences of Edvard Munch. The figures in the woodcuts of Erich Heckel are isolated, stoic and disconnected. Their brute faces seem animalistic. They appear as walking skeletons. In the shocking, neon, urban landscapes of Ernest Kirchner all of the figures are isolated, anonymous, alone in their struggle, except the prostitutes who seem happy, but who represent the ultimate commercialization and destruction of the human spirit.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - Street, Berlin, 1913, Oil on canvas, 47 1/2 x 35 7/8 in, 120.6 x 91.1 cm, MoMA Collection

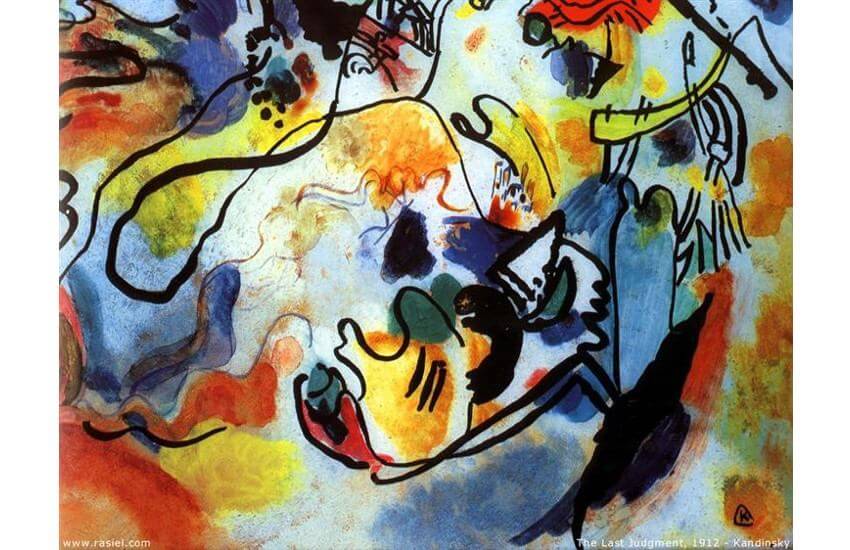

The Blue Riders

The other main German Expressionist group was called The Blue Rider. It included Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc and Paul Klee, among several others. They were named after a figure in a Kandinsky painting called The Last Judgment. The painting had been rejected from an exhibition on the grounds of its abstract content, and so Kandinsky invoked the painting as a symbolic reference.

In the painting, the Blue Rider symbolized the transition from the objective into the mystical world, which Kandinsky saw as analogous with the transition he and the others were attempting to achieve with their art. The painters of The Blue Rider relied less on form and figuration, and more on formal qualities such as color to convey emotional states. Their compositions were dramatic, vibrant and chaotic. They communicated a sense of violence and angst, but also hinted at cosmic brilliance and the underlying harmonies of the spiritual realm.

Wassily Kandinsky - The Last Judgment, 1912, Oil on canvas, Private Collection

Abstraction in Expressionism

Clearly many German Expressionists fully embraced abstraction in their work. They divorced color, form and line from objective representation, using them to convey emotional states and evoke emotional responses from viewers. But what can we say is abstract about the more figurative Expressionist work? One abstract element is certainly the reductive quality of their paintings. Everything not necessary to the composition drops away. This directly expresses the anxiety of the early 20th Century. Industry and war made many people feel that humanity was just a mass of anonymous, grotesque, shadow people. Anyone unnecessary seemed to drop away. Perhaps that is what people mean when they say that German Expressionist art is dark, anxious, frightening, primitive or crude.

But another abstract element of German Expressionism sends the opposite message. This element emanates from the swirling brushstrokes and the codified, symbolic imagery. So many figures in these paintings seem engulfed in a world without meaning. They are in motion, but surrounded by uncertainty. Yet they are emotive. That communicates something, if only abstractly. It says that the emotions of a single person matter. Whether it is the emotion of the painter, as with the paintings of Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, or the emotions of the figure in the work, as with the paintings of Edvard Munch, Erich Heckel and Ernest Kirchner, the Expressionists communicated that despite the tendency of modernity to make us feel dehumanized, the individual human spirit matters. That is indomitability. It is a belief that expressing oneself is always relevant. It is what inspired the Abstract Expressionists and the Neo-Expressionists, and what continues to inspire artists today. And it is what Ernst Kirchner meant when he said of the Expressionists, “Everyone who renders directly and honestly whatever drives him to create is one of us.”

Featured image: Edvard Munch - The Scream, 1893, Oil, tempura, and pastel on cardboard, 91 cm × 73.5 cm, 36 in × 28.9 in, National Gallery, Oslo, Norway

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio