Giorgio de Chirico and the Paintings Which Cannot be Seen

Are experiences concrete? Can feelings manifest? What beyond the observable universe exists? In 1911, when Giorgio de Chirico painted the first examples of Pittura Metafisica, or Metaphysical Painting, those were some of the questions he was attempting to confront. Like so many of his contemporaries, De Chirico was intimately aware that Western society was transforming in monumental and unstoppable ways. Rather than painting objective representations of that changing world, he chose instead to attempt to express the feelings of those who inhabited it. He was fascinated with how, when faced with the unknown, people take solace in the mystical, the mysterious and the extreme. As history was rapidly being gobbled up by a ravenous future, De Chirico wanted to portray that which could not be seen: the internal lives of time’s lonely, baffled witnesses. To do that he faced a great challenge: how to visualize that which is not visible. Inspired by the work of 19th Century Symbolists, De Chirico released himself from the burden of the real and took solace in the symbolic, the uncanny and the abstract. As he inscribed on the back of his self-portrait painted in 1911, “What shall I love if not the enigma?”

Rise of the Symbolists

Few know what it feels like to live at what the French call the fin de siècle, or the end of an era. Today there are so many of us and things change so quickly that somewhere in the world the end of an era occurs every day. Arguably, the last time human civilization experienced a communal fin de siècle was the end of the 19th Century. That was a time when unprecedented advancements occurred simultaneously in industry, technology, warfare, food production, medicine, transportation, communication, science, education and culture. So many radical changes were occurring all at once that it ripped humanity out of its sense of itself. The future made the past seem obsolete, which fundamentally transformed the way humans saw themselves, each other and the physical world.

For decades leading up to this global fin de siècle, the general mood of most people was not good. People were pessimistic and afraid. Those extremes of emotion manifested in the form of a cultural movement known as Symbolist Art. In the words of the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, the goal of the Symbolists was, “to depict not the thing but the effect it produces.” Symbolist paintings are moody and represent extreme points of view. Viewers are often overcome by the emotions they convey. Their subject matter is irrelevant. What matters is how they make people feel.

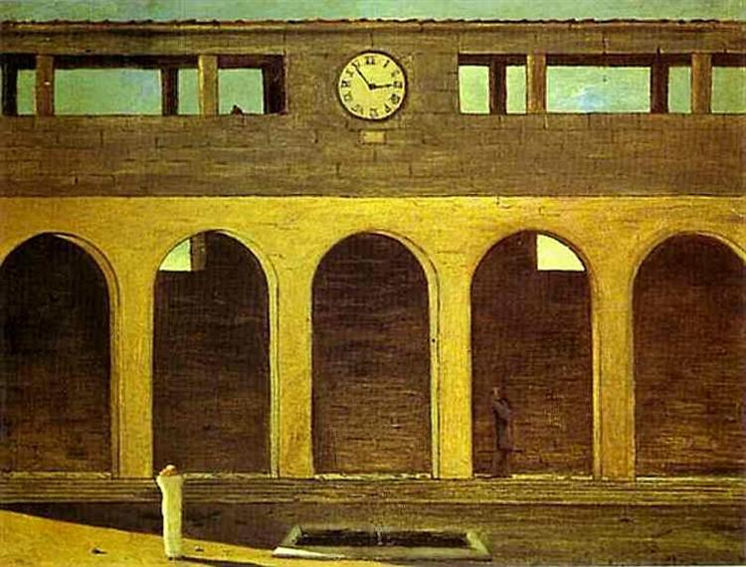

Giorgio de Chirico - The Enigma of the Hour, 1911. Private Collection

Giorgio De Chirico in Munich

In 1988 when Giorgio De Chirico was born, the fin de siècle was in full swing.De Chirico was born in Greece to Italian parents. When Giorgio was 17 his father died. The next year, Giorgio moved to Munich and enrolled in art classes. He studied classical painting techniques and read philosophy, in particular the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, who believed that human behavior is determined by an attempt to fulfill unknown desires based on metaphysical angst. Also while in Munich, De Chirico became acquainted with the uncanny paintings of the Symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin, which addressed modern fears and anxieties with classical imagery and iconography.

De Chirico moved to Italy after school. While living in Milan, Florence and Turin he was confronted by the stark ways Italy’s ancient architecture contrasted with its modernizing culture. He described how the metaphysical quality of the environment filled him with an overwhelming sense of melancholy. In 1910, while in Florence, he expressed that feeling through a series of innovative and highly stylized paintings including The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon and The Enigma of the Oracle. The stark lighting, isolated figures and mix of contemporary and classical iconography became integral to De Chirico’s signature style, which would later be known as Metaphysical Painting.

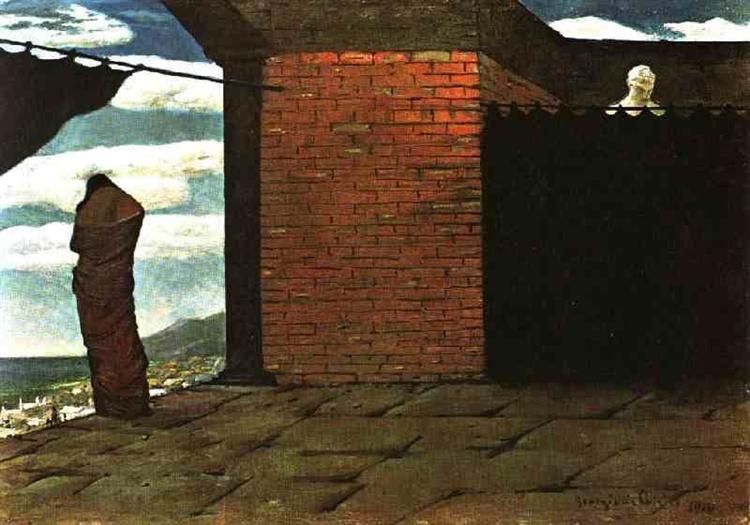

Giorgio de Chirico - The Enigma of the Oracle, 1911. Oil on canvas.

Making the Invisible Visible

What was De Chirico attempting to convey with his “enigma” paintings? The isolated statues, the dark curtains hiding part of the picture, the figures with their backs turned, the harsh differences between shadow and light. These are images of a world full of relics and mystery, of mystic secrets from the past. They are images of private moments full of unknown worries. Though figurative, these pictures are richly symbolic. Rather than attempting to clarify, they are happily abstracting the facts, blurring the message, making the content non-interpretable except for the mood.

Over the years he added additional abstract symbols that further confuse the meaning of his images, while increasing their sense of moodiness and melancholy. He added a recurring image of a train, always in the distance, always belching tiny puffs of smoke as it passes by. He added clocks, such a symbol of longing as moments, like lonely trains and sailing ships, pass by. And then there are the towers, alone overlooking the landscape, their lonely points of view objectified and marginalized as they slip into the distance. The images are uncanny—familiar and yet unfamiliar—like dreams.

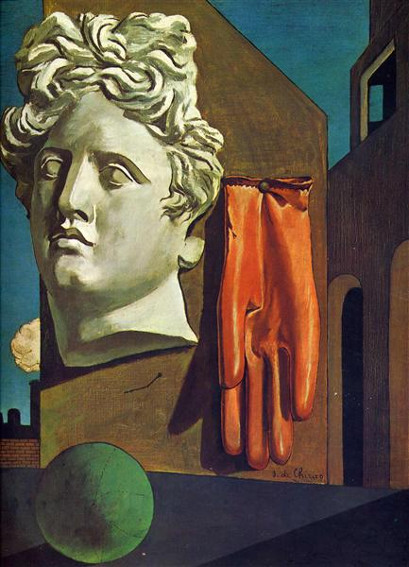

Giorgio de Chirico - The Song of Love, 1914. Oil on canvas. 28 3/4 x 23 3/8" (73 x 59.1 cm). Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Collection. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Symbolism Expanded

In 1911, De Chirico moved to Paris where he experienced a great deal of interest in his unique new style. His work was included in several major exhibitions and he caught the eye of the influential art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who helped him acquire an art dealer. But in 1915 when World War I broke out, De Chirico returned to Italy, like so many other European artists who were compelled to return to their homeland to fight. Though this could have destroyed his momentum he experienced a mystical twist of fate. Deemed physically unfit for battle, De Chirico was stationed to work in a hospital. There, he met the painter Carlo Carrà, a painter who shared De Chirico’s abstract, symbolic vision.

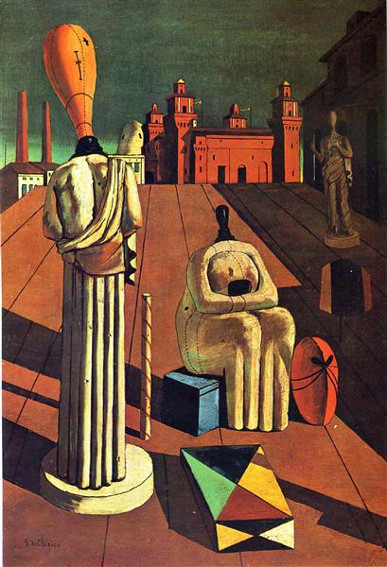

Carrà’s companionship resulted in a deepening of De Chirico’s reliance on abstract symbolism. His paintings began to include even more dreamlike imagery, contributing to an ever more uncanny visual language. The nature of this new imagery was entirely relevant to the circumstances that had caused the Great War. So many were being left behind, forlornly wandering through the desolate, lonely arcade of the past, without purpose and without direction. De Chirico addressed themes of love, inspiration and ghosts, placing odd arrangements of material objects in starkly lit places, creating an aesthetic menagerie informed by confusion and a loss of identity.

Giorgio de Chirico - The Disquieting Muses, 1916 - 1918. Private Collection

Influence on the Surrealists

In the years following the war, De Chirico’s vision was widely embraced and his fame was rapidly increasing. Yet he considered his style to be immature. So in 1919, De Chirico decided to abandon Metaphysical Painting. In his essay The Return of Craftsmanship, he announced his intent to objective iconography and classical subject matter.

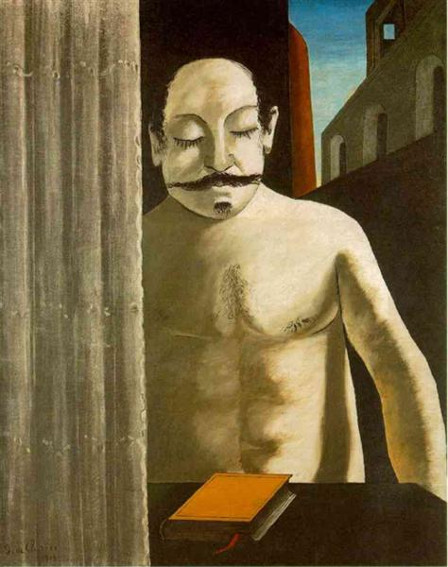

The irony of De Chirico’s timing was that just one year later the Surrealist writer André Breton would see one of his paintings, The Child’s Brain, hanging in a gallery window. That random encounter would then lead an entire generation of young painters, including Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, to become interested in De Chirico’s work. These painters, who would become known as the Surrealists, were inspired by the dream-like quality of these paintings and the way they tapped into the abstract aesthetic of the subconscious.

Giorgio de Chirico - The Child's Brain, 1917. Oil on canvas. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden

The Contemporary Metaphysical Legacy

In addition to creating a uniquely mesmerizing style, De Chirico’s attempts to paint “that which cannot be seen” left behind a trail of aesthetic breadcrumbs. We can follow it whenever we wish to return to our primordial symbolic roots to confront our own questions about the essence of being, the nature of time or the mysteries of space, or when we are troubled by our own daily sense of the unending fin de siècle. Because although we possess much more data about our world than did our early 20th Century ancestors, much still remains that is unseen.

Despite our scientific advances we are no closer than De Chirico was to answering the essential questions of Metaphysics, such as, “What does it mean to exist?” We have not answered the question of whether we are only bodies or whether the soul exists, and if it does whether all things have a soul or whether only living things do. But thanks to artists like De Chirico we have models for the integration of symbolism, art and mystery with our lives. We may still be the lonely, baffled witnesses of time, but we are at least perhaps closer to accepting our inherent Metaphysical ambiguity, so that we might yet learn to love, rather than fear, the enduring mysteries of our existence.

Featured Image: Giorgio de Chirico - The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon, 1910

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio