Golden Ratio in the Art of Abstraction

One definition we’ve heard of a good abstract painting is “any abstract painting someone enjoys being around.” But what exactly makes someone enjoy being around one abstract painting over another? Some say an ancient formula holds sway over aesthetic phenomena, silently manipulating what we like. Its name? The Golden Ratio. And art isn’t the only place the Golden Ratio shows up. It’s a mathematical equation as old as math itself, and it supposedly helps determine why one building appears more inviting than another, why one face looks friendlier than another, and why one painting is more likable, and subsequently more precious.

Trust Us, This Is Beautiful – The Golden Ratio in Art

Conceptually, the Golden Ratio has popped up in many different cultures and been known by many names. It can be applied to numbers, to space, to distances, or to anything else that can be increased or divided up. Indian mathematicians in 450 BC called it “misrau cha.” The Greeks called it “phi.” Medieval Italians expressed the idea with “Fibonacci numbers.” As a decimal, it’s expressed like this: 1.61803398875. But what does it look like? That’s the important thing for us.

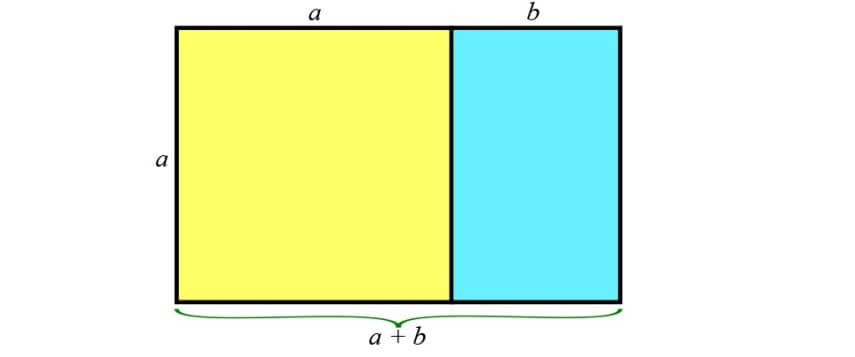

Think in terms of two-dimensional space. Imagine a rectangle. Within the rectangle is a square that takes up .61803398875 of the space. Something like this:

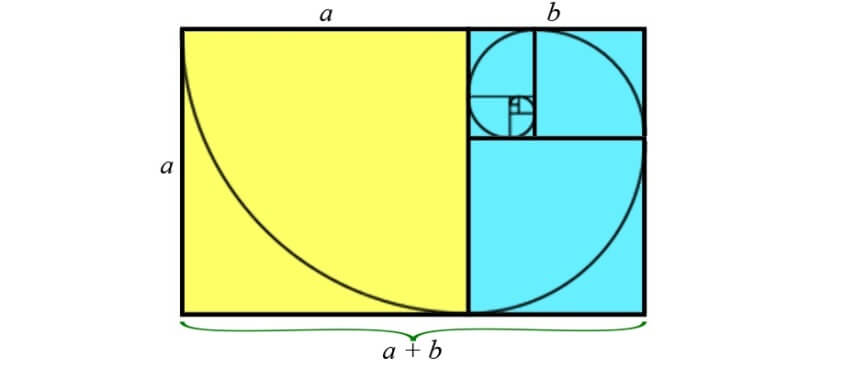

This rectangle is the perfect expression of the Golden Ratio. And now the smaller rectangle to the right of the square could also be divided up the same way. And then the resulting smaller rectangle within that rectangle could also be divided up the same way. And so on.

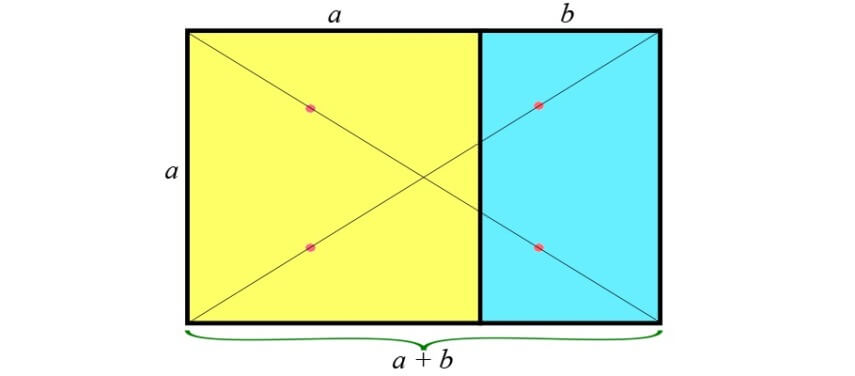

What makes this important to artists is that, aesthetically, it’s said that if you start with a Golden Ratio rectangle then draw an X connecting the opposite corners then draw dots at the center of each of the four cross sections of the X, those four points are unavoidably the most aesthetically pleasing areas of the rectangle. Ergo, an artist wishing to make optimum use of the human eye’s natural attraction to the Golden Ratio should place visual elements of importance to their painting in one or more of those general areas.

There are several ways the concept of the Golden Ratio can be expressed in an abstract painting using visual shorthand. One is to simply utilize the Golden Ratio in its most obvious way, which is to place important visual elements in the fore mentioned sweet spots of the painting. Another is to incorporate Golden Ratio rectangles directly into the work. Another is to insert facsimiles of the Greek letter phi, which stands for the Golden Ratio: φ. Or another is with a spiral, which can represent the curved arches connecting subsequent Golden Ratio rectangles:

There’s Golden Ratios in Them!

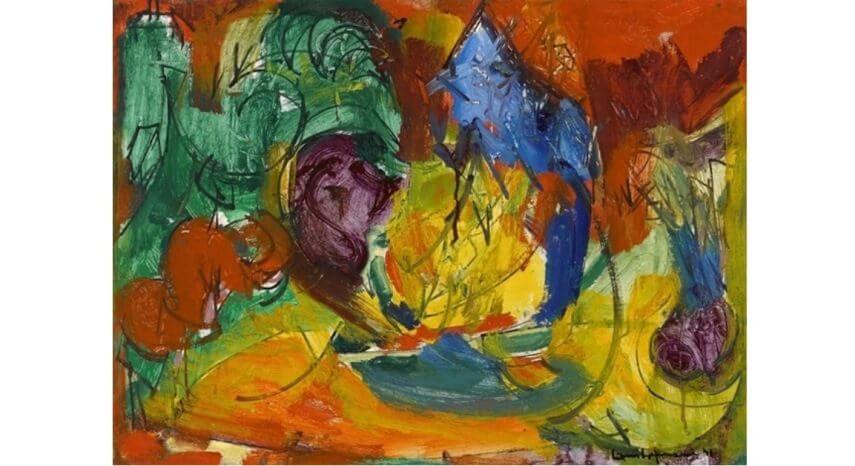

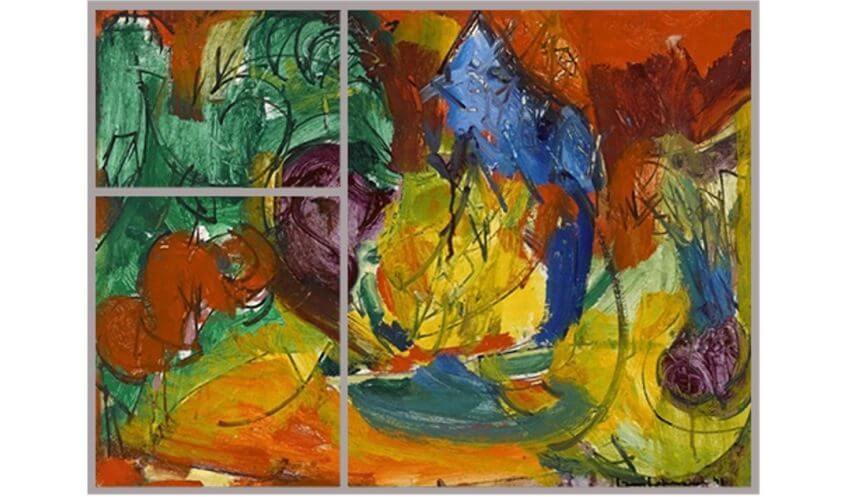

The father of Modernism Hans Hofmann was a natural at utilizing the Golden Ratio in his paintings. In his abstracted landscape Miller Hill, he organizes the tightest cluster of forms around the upper left Golden Ratio sweet spot. When a Golden Ratio grid is placed over this painting, we also discover that Hofmann has incidentally placed a spiral in the smaller rectangle within the rectangle within the rectangle.

Hans Hofmann - Miller Hill, 1941, Oil on panel, 44.8 x 61 cm. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Who can say whether Hofmann placed that spiral as a coded reference to the Golden Ratio? Perhaps it was just a fascinating accident. But in an untitled abstract Hofmann painting from 1945 we find a similar placement occur as well, with a spiral being added in the smaller rectangle within the rectangle, and the most active abstract forms occupying spaces around the four Golden Ratio sweet spots.

Hans Hofmann - Untitled, 1945 Oil on panel, 42.7 x 30.7 in. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Golden Ratio symbolizes balance, stability, perfection and strength. It is easy to see the attraction of adding references to it, or utilizing it mathematically in an otherwise chaotic composition. Whether it was his intention or not, it’s tempting to believe that Hofmann was aware of this formula and its connotations. In a painting Hofmann created near the end of his career, he presents multiple rectangular forms layered amidst and atop of each other, several of which follow the Golden Ratio. The painting is named in honor of his beloved, departed wife, Miz. Its subtitle, Pax Vobiscum, means “peace with you.”

Hans Hofmann - To Miz - Pax Vobiscum, 1964, Oil on canvas, 212.4 x 196.5 cm. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Can You Feel It?

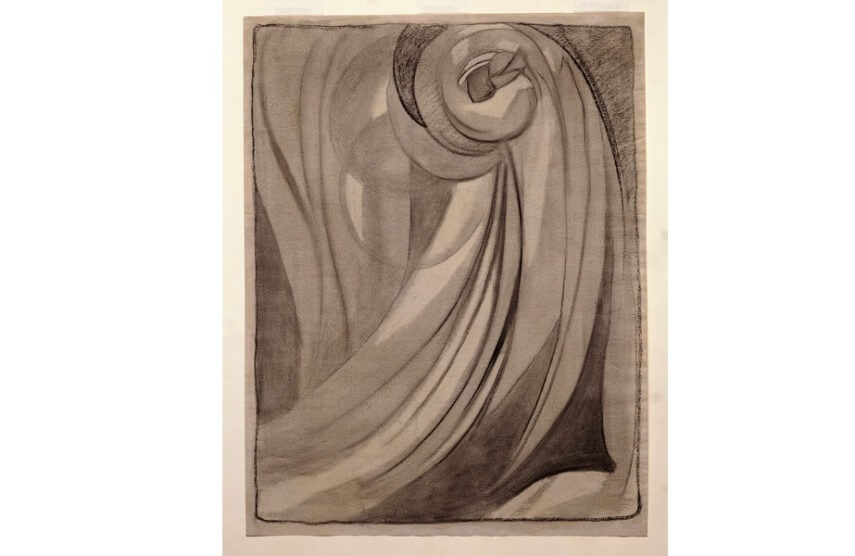

Once we grasp the basic visual representations of the Golden Ratio, we begin to see it almost everywhere we look. We see it manifest in so many works by the greatest abstract artists. We see it in the late paintings of Robert Motherwell. We see it hidden in plain sight in Rothko’s color fields. We recognize it’s hidden symbols in O’Keeffe’s charcoal drawings. We see it occupying every inch of Piet Mondrian’s De Stijl compositions.

Mark Rothko - No. 8, 1949, Oil and mixed media on canvas, overall: 228.3 x 167.3 cm (89 7/8 x 65 7/8 in.). National Gallery of Art. Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc. 1986.43.147. On View: East Building, Tower - Gallery 615A. Copyright © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko

Ancient Equation of Beauty

When we really start looking for it, we might even go a little crazy believing we see the Golden Ratio present in every rectangular abstract painting we see. And maybe it truly is there. Maybe it’s a secret symbol left behind by the artist for those who are in the know. Maybe it’s a breadcrumb to help the viewer’s subconscious find its way. Or perhaps many abstract artists have simply internalized this ancient equation of beauty. Maybe by instinct, through some primordial function of the universal vibe, this expression of balance, strength, harmony and aesthetic pleasure asserts itself automatically into some works of abstract art, so that it may also take harbor in the mind of the viewer. Maybe beauty just finds a way.

Georgia O'Keeffe - Early No. 2, 1915, Charcoal on paper. Sheet: 24 × 18 ½ in. (61 × 47 cm). Work on paper (Drawing). The Menil Collection. Gift of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation. 1994-55. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Featured Image: Robert Motherwell - Dance, 1981, Acrylic on canvas, 84 1/4 x 126 1/8 in. North Carolina Museum of Art.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio