Gottfried Jäger - Pioneer of Contemporary Abstract Photography

A dual evolution has been going on between computers and humans for some time, and German abstract photographer Gottfried Jäger could be considered one of the earliest examples of a cross-over being. In the late 1950s, Jäger pioneered a field of aesthetic inquiry known as Generative Photography—an approach to making abstract photographic images using predetermined systems rather than individual artistic choices. In a way, Generative Photography is akin to various other art styles in which the process is more important than the end product. But in another way, it was an early step toward what I call I.A., or Intelligent Artifice—the moment that seems to be coming one day when humanity will cease to be self-aware. It is the complementary phenomenon to A.I., or Artificial Intelligence, when computers will one day think for themselves. The first electronic computational machine was invented in the 1800s by Charles Babbage, a British mechanical engineer. And ever since, subsequent generations of engineers have been striving to make computers more like the humans for whom they work. Their ultimate goal is to create machines that do not require human input in order to work. And alongside that quest, some humans have been striving to become more computer-like. Although this may seem like a frightening proposition, the work Jäger does demonstrates the possibility that taking decisions out of the hands of a creative human being may not mean the end of humanity. It could simply mean freeing up the mind to do other things, such as contemplating what the meaning of life and art might truly be.

Origin Stories

The most difficult challenge abstract photographers face is the history of their own medium. Photography was invented as a tool for capturing images of recognizable phenomena. To use it abstractly therefore invites criticism. No how abstract a photograph seems, viewers want to know what they are looking at. The goal of the abstract photographer is to release the photograph from that bondage: to allow it to become something other than a representation of something else—to free it to be its own object. That was on the mind of Gottfried Jäger when he first began experimenting with abstract photography in 1958. It informed his earliest works—photos of symmetrical things, an effort to be concrete, to prioritize pattern, shape, and form over the object being photographed.

But no matter how he tried to obscure it, the object he was photographing nonetheless expressed itself. So next he turned to the idea of serialization. In a series called Themes and Variations, he took multiple photographs of the same subject—for example a spot of rust. He photographed is in every conceivable way—blurry, in focus, extremely close up, in multiples, from different perspectives, etc. The result was more satisfactory. When showed together, these series of images opened the door for viewers, allowing them to forget about what was being photographed, i.e. the rust spot, and to think instead about the aesthetic range of visual effects they were seeing. They appreciated the forms, the shapes, the patterns and the compositions with less regard for the realistic subject matter.

Gottfried Jäger - Rost Thema 1, 1962 (Left) and Rost Thema 1-2, 1962 (Right), © Gottfried Jäger

Gottfried Jäger - Rost Thema 1, 1962 (Left) and Rost Thema 1-2, 1962 (Right), © Gottfried Jäger

Systems and Choices

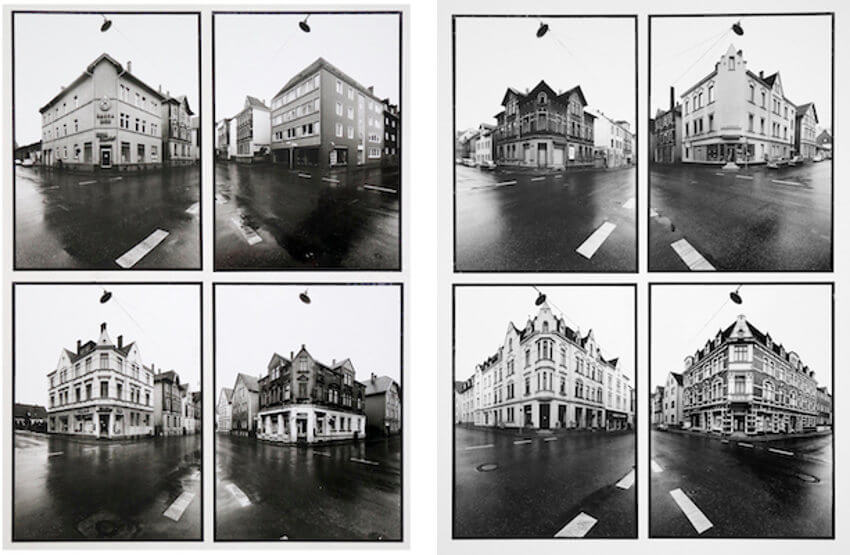

But one problems still remained for Jäger in his quest for photographic abstraction—he was still making critical choices about what pictures to take and how to take them. His ego was still determining the outcome of the work, so expressionistic sensibility still had the potential to affect how viewers perceive the pictures. To eliminate that aspect of his work, he adopted a more analytical, computational approach to picture taking. He developed a system then allowed that system to tell him what each picture in a series would be. In a series titled Arndt Street, he photographed a street by using the predetermined system of corner perspective. He describes it as, “A photographic documentation of the development of a street depicted through examples of corner buildings.” The series makes it impossible not to be contemplative of the inherent abstractions associated with the formal qualities of the pictures.

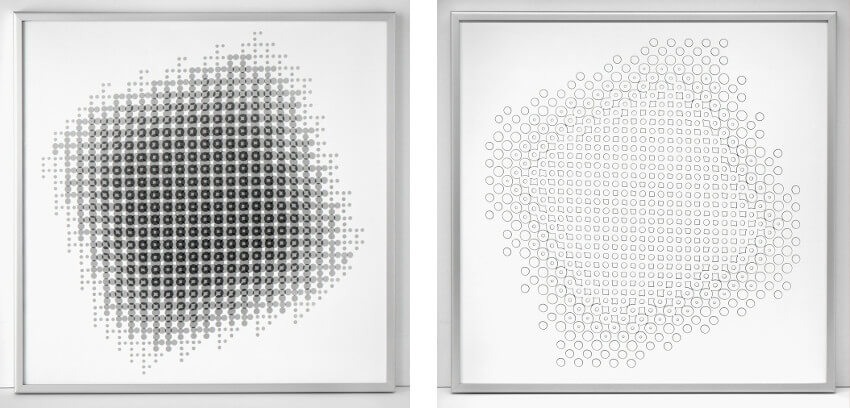

But even these pictures were trapped in reality. They depicted something recognizable to viewers. So the next step for Jäger was to reduce photography to its essentials: light and dark. Rather than photographing things, he determined to create a light painting—a composition constructed solely from light and a light-sensitive surface. To achieve this, he invented a multi-pinhole camera. All of the elements that would determine the outcome of the picture, such as the arrangement of the pinholes, the quality of the light, the exposure time and the f-stop, were determined by systems, so the final composition would be generative rather than expressive. The process yielded images that are both truly abstract and truly concrete—images that relate only to themselves.

Gottfried Jäger - Arndt 02, 1971 (Left) and Arndt 03, 1971 (Right), © Gottfried Jäger

Gottfried Jäger - Arndt 02, 1971 (Left) and Arndt 03, 1971 (Right), © Gottfried Jäger

Seeing Ourselves

Aside from those aforementioned, Jäger has created dozens of other bodies of work. He has experimented with photographing computer screens, with color studies, and with a multitude of materials and conditions, tirelessly exploring the range of his theoretical approach. A full catalogue of his work is on his website . It was while looking over those series that it became clear to me how computer like the oeuvre of this artist is, and yet how inherently human it makes me feel.

Jäger has not only succeeded as an abstract photographer by reducing the physical world to an aesthetic world of forms, shapes, patterns and compositions. He has also elevated the study of those forms in such a way that I question what their meaning and value is. He has made me question relationships between the elements more than the elements themselves. That has helped me understand more clearly the point of Generative Art, and any other art that seeks to hide the hand of the artist. It brings to the forefront the idea that there are more important things in this world than ego, and that the most important things we see may be the things we recognize the least.

Gottfried Jäger - Pinhole Structure 3.8.14 B 2.6, 1967, Silver gelatin print on baryta paper, 19 7/10 × 19 7/10 in, 50 × 50 cm (Left) and Pinhole Structures 3.8.14 D 7, 1.3, 1973, Silver gelatin print on baryta paper, 19 7/10 × 19 7/10 in, 50 × 50 cm (Right) © Gottfried Jäger and SCHEUBLEIN + BAK, Zürich

Gottfried Jäger - Pinhole Structure 3.8.14 B 2.6, 1967, Silver gelatin print on baryta paper, 19 7/10 × 19 7/10 in, 50 × 50 cm (Left) and Pinhole Structures 3.8.14 D 7, 1.3, 1973, Silver gelatin print on baryta paper, 19 7/10 × 19 7/10 in, 50 × 50 cm (Right) © Gottfried Jäger and SCHEUBLEIN + BAK, Zürich

Featured image: Gottfried Jäger - Kniff,2006,Photo paper work V, Gelatin Silver Barite paper (Ilford Multigrade IV), 19 7/10 × 23 3/5 in, 50 × 60 cm, © Gottfried Jäger and SCHEUBLEIN + BAK, Zürich

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio