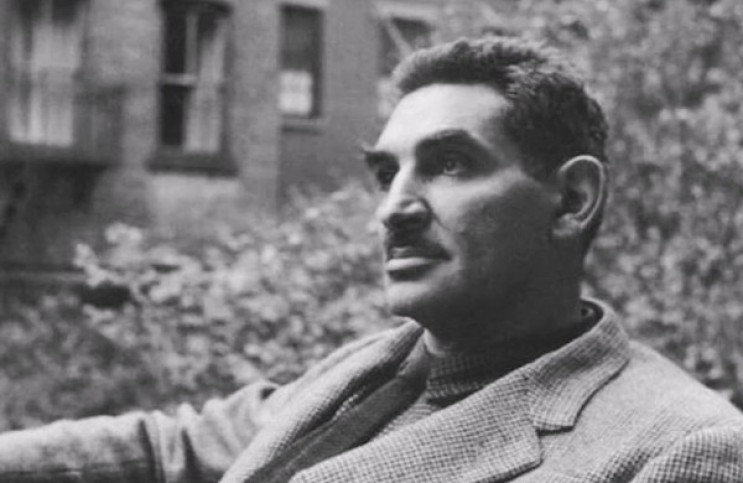

Why Harold Rosenberg Was Seminal for Abstract Expressionism

Oct 22, 2018

Harold Rosenberg (1906 – 1978) is the art critic most often credited with helping Abstract Expressionism gain a foothold as a mainstream American art movement. But it could also be said that Abstract Expressionism is the art movement that helped Harold Rosenberg gain a foothold as a mainstream American art critic. The connection between Rosenberg and Abstract Expressionism reminds me of the quote by indigenous Australian artist Lilla Watson: “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” Rosenberg liberated Abstract Expressionism by publishing an essay in the December 1952 issue of ARTnews, titled “American Action Painters.” That essay contained the now famous quote, “At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act-rather than as a space in which to reproduce, re-design, analyze or express an object, actual or imagined. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.” It coined the term “Action Painting” and defined Abstract Expressionist not as a formal, academic type of painting, but as an emotional art style in which practitioners conjured unique, idiosyncratic visual voices from the inner reaches of their own subconsciouses. In turn, Abstract Expressionism liberated Rosenberg by saving him from being known solely as a marxist social critic. The most famous thing Rosenberg had written prior to “American Action Painters” was a scathing criticism of capitalist culture published in 1948 under the title, “The Herd of Independent Minds: Has the Avant-Garde Its Own Mass Culture?” His defense of Abstract Expressionism constructed a theoretical refuge where artists could experiment freely, and established him as one of the leading artistic thinkers of his time.

All People Are Not Alike

Although he had been writing for a decade prior, Rosenberg really came to prominence as an essayist in the years immediately following World War II. He had witnessed the American War Machine become transformed into the American Consumerism Machine. The frenzy to sell culture to a mass audience disgusted Rosenberg, who had always believed in the sanctity of art as something subjective and personal. The main point he made in his “Herd of Independent Minds” essay is that those who try to sell cultural products to the masses essentially think all people are alike—not equal mind you, but actually the same. He writes, “So deeply is [the mass-culture maker] committed to the concept that men are alike that he may even fancy that there exists a kind of human dead center in which everyone is identical...and that if he can hit that psychic bullseye he can make all of mankind twitch at once.”

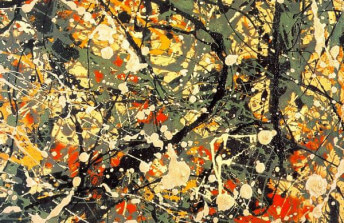

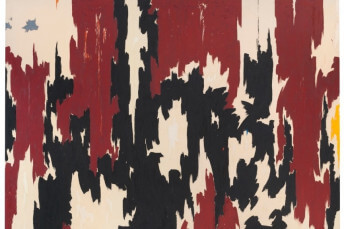

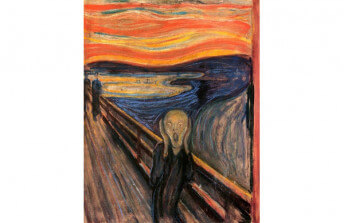

The year before Rosenberg wrote that essay, Jackson Pollock made his first drip paintings. Artists like Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Franz Klein, Adolph Gottlieb, and Clyfford Still fascinated Rosenberg because they embraced the Surrealist idea of automatic drawing. Rosenberg believed all of the history of painting prior had been based on painting what already existed, either objects or ideas. He even considered the abstractionists of Europe, like Kandinsky and Mondrian, to be working from ideas that existed in their minds prior to beginning their paintings. On the contrary, he saw Abstract Expressionists approaching their canvasses with no pre-existing notions at all of what might come out. The moment they started to paint was a movement of discovery even for them. These physical events were thus utterly unique, and the resulting paintings were irreproducible relics of the process of their creation. Unlike the mass-culture makers Rosenberg despised, he saw the Abstract Expressionists as singular-culture makers. In their efforts he saw the salvation of the avant-garde.

Inseparable from Biography

The second essential point Rosenberg made in “American Action Painters” was that the works of the Abstract Expressionists were inseparable from the biographies of the artists who painted them. This, he argued, was also unique in the history of art. In the past, he believed, when artists sat down and painted, say, a portrait, though that experience might technically be part of their life story, it was not remarkable enough to be considered biographical. Any other artist could sit and paint a similar portrait, or copy the portrait that the original artist made. To Rosenberg, copying something that already exists is not an experience worth touting. On the contrary, he felt the Abstract Expressionists had completely freed themselves from existing content and subject matter. He considered the instinctive, performative, completely original painting events they instigated to be extraordinary and the work they produced to be inseparable from the individual artists. Not only did he consider Abstract Expressionist paintings to reveal the hand of the artist, be believed they contained some unique aspect of their very essence.

Perhaps Rosenberg might sound a little hyperbolic. Yet the mythos he created about Abstract Expressionism succeeded in sparking widespread interest in the movement. To this day, the artists associated with Action Painting are heralded as staunch individuals who laid their hearts and minds and spirits bare in their work. Furthermore, even though public attention moved on to other movements eventually, the substance of what Rosenberg wrote about Abstract Expressionism went on to affect many other aspects of the global art world. Allen Krapow embraced the idea of action-art when he created his Happenings in the 1950s and 60s. The Gutai Group in Japan and the international Fluxus Movement were also both heavily influenced by the notion of the primacy of personal creative action over artistic relics. Movements like Process Art, Performance Art, and even Social Practice Art all have their roots in what Rosenberg said about Action Painting. His influence thus goes far beyond Abstract Expressionism, or even any of those other movements. What Rosenberg truly achieved was the dissemination of what he called “a new creative principle.” He elucidated a fresh way of looking at painting that forever changed the way humanity understands the processes and purposes of all art.

Featured image: Harold Rosenberg - portrait. Credit: Maurice Berezov photo copyright A.E. Artworks , LLC

By Phillip Barcio