The (Un)Intentional Controversy in Hermann Nitsch Art

I am a vegetarian. I usually keep that information private because it is irrelevant to almost any professional conversation I would normally have about art. But today I am writing about Hermann Nitsch. And as anyone who knows anything about this particular artist can tell you, where one stands on issues of animal rights is paramount to any discussion about Nitsch and his art. The work Nitsch does involves the use of the blood, entrails and carcasses of animals as an artistic medium. Many people find it disturbing or morally egregious. There are even some places where it is considered illegal. But of course an artist making work that offends certain members of the public, or that is considered illegal, is nothing new. Nonetheless, for some reason when it comes to Hermann Nitsch, that is almost all people want to talk about. Hundreds of articles have been written about Nitsch. Every writer whose coverage I have read has devoted far more space to the public perception of disgust that surrounds his work than to any meaningful analyses of its value as art. That is unfortunate, because the disgust people project toward Nitsch says very little about Hermann Nitsch. It says far more about the people projecting it. The carnage that accompanies the performances Nitsch stages is nothing compared to what a typical worker in a commercial slaughterhouse sees five minutes into an average shift. It is precisely because I respect animals that I advocate in favor of Nitsch. I believe the work he does is important, and worthy of more serious consideration than it has yet been given.

The Orgies Mystery Theater

Hermann Nitsch was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1938. He graduated from the School of Graphic Design and Photography in Vienna in 1957. That same year, he wrote a 1,595-page theatrical script detailing his vision for what he called an action: an artistic performance designed to engage the public in a direct, realistic, and visceral way. The script described a ritualistic melodrama, a sort of mock-religious ceremony, which, like many real religious ceremonies, would incorporate the blood and body of a sacrificially slaughtered animal. Titling his melodrama The Orgies Mystery Theater, he envisioned it as something that would play out over his entire lifetime in a series of public performances. Some, he imagined, would last for multiple days, involve scores of actors, and be viewed by hundreds of spectators. He furthermore imagined that despite the lengthy script he had written, the actions would be partially improvised in order to make them as true to life as art can conceivably be.

The first episode of The Orgies Mystery Theater was staged in an apartment in Vienna in 1962. On his website, Nitsch describes the action as follows: “crucifixion and splattering of a human body, vienna, apartment, 30 min.” Descriptions of the event from spectators state that Nitsch enlisted a group of his friends as performers, and that they acquired the body of a slaughtered lamb to use in the performance. Partway through the spectacle, the police shut it down, at which point Nitsch and his friends are said to have fled through the city streets, allegedly ditching the carcass of the lamb in the Danube River. Subsequently, in the 55 years since that night, Nitsch has performed more than 150 more actions, all exploring the same basic concept, although in increasingly elaborate ways. Some have taken place in galleries, some in public, and many have taken place in Prinzendorf Castle, which Nitsch acquired from the Catholic Church in 1971 to use as his home and performance museum.

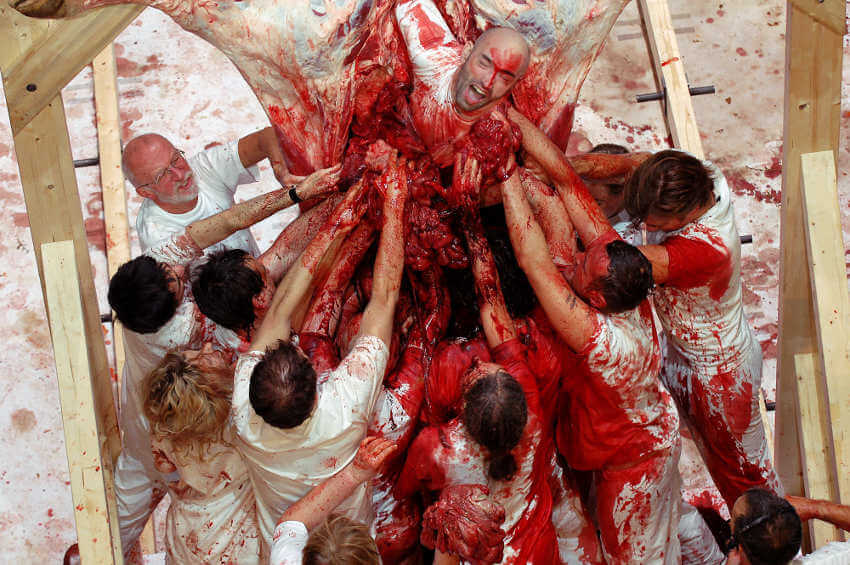

Hermann Nitsch - Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries 15, 2005, photo by Georg Soulek, via theculturetrip.com

Hermann Nitsch - Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries 15, 2005, photo by Georg Soulek, via theculturetrip.com

The Problem With Performance Art

As outrageous as his concept may seem, Nitsch did not develop it in a vacuum. Performance as an art form was nothing new. Neither were staged, ritualistic tragedies involving the use of animal blood. Both have been a relatively steady part of human civilization for what? Forever? But in the late 1950s, modern conceptual Performance Art was one of the most exciting frontiers of the global avant-garde. And one of the main concerns for many artists working in the form then, as with now, was that performance art has the potential to be so obviously false, and therefore so agonizingly boring. The challenge many artists were undertaking was to discover ways in which a performance could be real, and therefore truthful. Ideally, they realized, something should actually be at stake during the performance, a circumstance which would create undeniable drama for the audience to behold.

One of the great, early successes in this realm took place in Japan in 1955, when Kazuo Shiraga of the Gutai Group performed Challenge to the Mud. For this performance, while dressed only in a mawashi, Shiraga wrestled on the ground with a giant puddle of mud. At the conclusion of the performance, he left the mud puddle in place, roped off for viewers to look at, like an action painting: an aesthetic relic of an act. In 1959, Yves Klein improved further on the concept with a conceptual performance called Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility, which took the step of involving the spectator physically in the performance. Klein sold spectators empty spaces around the city of Paris. He gave them a certificate of ownership over an immaterial zone in exchange for a very real amount of gold. If the buyer chose, Klein then completed the ritualistic exchange of value by burning the certificate of ownership and throwing half of the amount of gold into the Seine. Klein proved that if the viewer also has something at stake in the performance it can provoke a more lasting and profound effect.

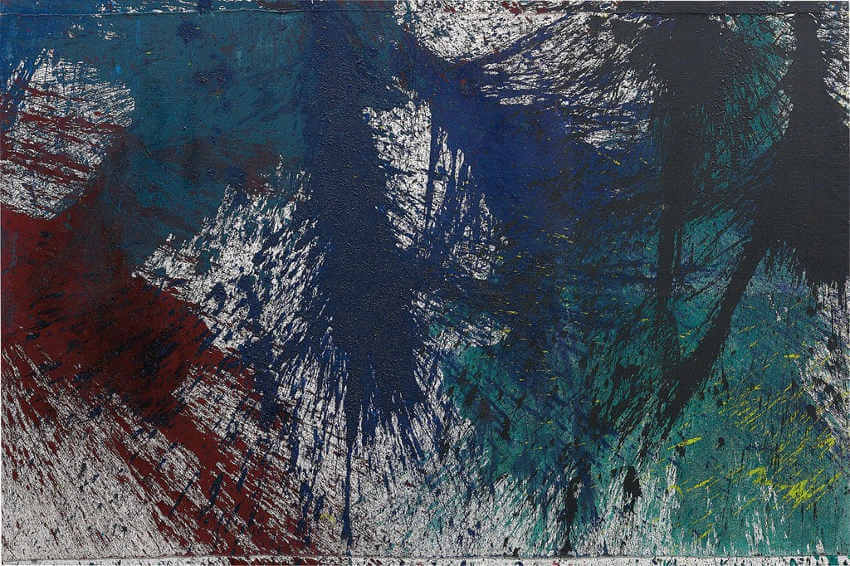

Hermann Nitsch - Untitled, 2006, Acrylic on jute, 78 3/4 × 118 1/8 in, 200 × 300 cm

Hermann Nitsch - Untitled, 2006, Acrylic on jute, 78 3/4 × 118 1/8 in, 200 × 300 cm

What Is At Stake

In a way, it could be argued that The Orgies Mystery Theater actually took a step backwards from the work of Yves Klein, because it does not ask the audience to do anything but watch. But in another way, it could be said that it took a conceptual leap forward, because what Hermann Nitsch realized is that content alone, if chosen correctly, can force conscientious human beings to feel they have something at stake, thus enlisting them as performers, not physically, but on a psychological level. And as Nitsch realized, the one source of content that never fails to get audiences psychologically engaged is the topic of life and death.

As Nitsch has said, “with my work I want to stir up the audience, the participants of my performances. I want to arouse them by the means of sensual intensity and to bring them an understanding of their existence. Intensity is an awakening into being.” Most of us never really think about the fantastical unlikelihood of our existence. That we have a life at all is astounding. But we ignore it in pursuit of a lifestyle or a livelihood. Then when we see a sentient being die, or we see the carnage that so often accompanies a recently deceased animal, the reality of death is thrust upon us. Nitsch wants us not to look away from that. He does not want to disgust us. He wants us to look at his art and think about life and death. He wants us to converse about it.

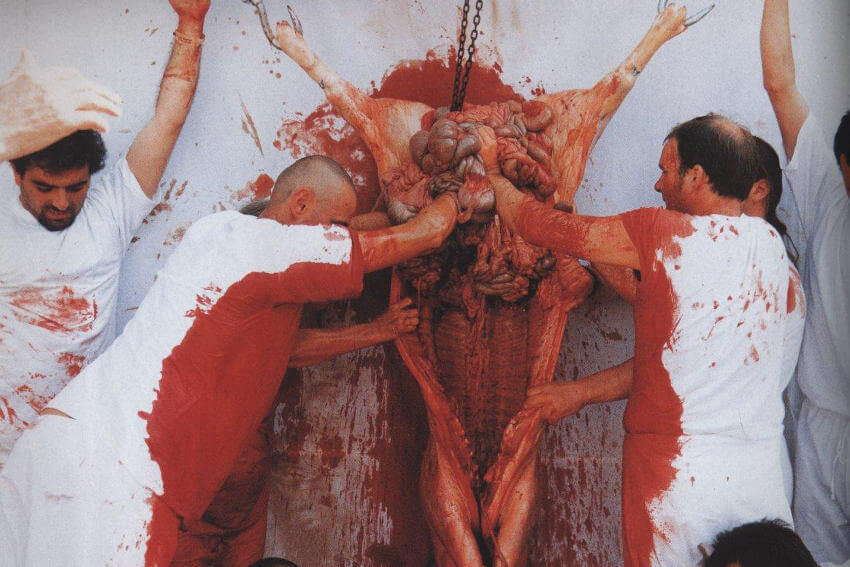

Hermann Nitsch - Orgies Mysteries Theater, photo via rudedo.be

Hermann Nitsch - Orgies Mysteries Theater, photo via rudedo.be

This Is Us

One of the key things to realize about The Orgies Mystery Theater is that Nitsch says he only uses animals that have already been selected to be commercially slaughtered. He ensures they are killed humanely, and their meat is consumed in the feasts that accompany his performances. Nonetheless, he has been cited for violating the Universal Declaration of Animal Rights, instituted by UNESCO in 1978, which states as its first article: “All animals are born with an equal claim on life and the same rights to existence.” As a vegetarian and a person who respects animals, I agree with the Universal Declaration of Animal Rights, without reservation. But as a logical person I have to point out that it is absurd to criticize this one artist for violating its terms.

The Universal Declaration of Animal Rights is violated every time a child throws uneaten chicken wings in the trash, or a well-fed adult orders a 36-ounce steak at dinner. What respect do the rest of us have for animal rights to existence? We hire others to do the dirty work so we do not ever have to see the filth, misery and carnage that occur every hour of every day all over the world because of our ambivalence. Nitsch is saying, “Do not turn away. Look. This is what you are.” As someone who has witnessed the daily “actions” that occur in butcher shops, meat processing plants, and on factory farms, I can honestly say the actions of Hermann Nitsch are quaint in comparison. If you find his work controversial, disgusting, or morally egregious, what does that say about you?

Hermann Nitsch - Action 122 at the Burgtheater, Vienna, 2005, photo via vice.com

Hermann Nitsch - Action 122 at the Burgtheater, Vienna, 2005, photo via vice.com

Featured image: Hermann Nitsch -Untitled, 2002, Acrylic on jute, 78 7/10 × 118 1/10 in, 200 × 300 cm

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio