When Hilla Rebay Became the Guiding Spirit of the Guggenheim Museum

We are approaching the 50th anniversary of the death of a great woman, without whom abstract art history as we know it would not exist. The Baroness Hildegard Anna Augusta Elizabeth Freiin Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, more simply known as Hilla Rebay, died 27 September, 1967. If you have never heard the name Hilla Rebay it is likely thanks to her enemies. In her lifetime, Rebay was hated by several of the wealthiest, most powerful members of the New York social elite. Her foes made a concerted effort to denigrate her, and when they got the chance they worked to hideany trace of her influence. So successful were their efforts that Rebay was reduced for the most part to a footnote in the art historical record. But in recent years, the truth about Hilla Rebay has becoming known. Here is an introduction to the story of this fascinating woman who left behind a legacy more valuable than anyone can truly know.

Haters Will Hate

Hilla Rebay left behind a monumental mark. The most lasting legacy of her influence is a modest, spiraling building on the Upper East Side of New York City. It is sometimes referred to as the temple to non-objective art, but you probably know it better as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Without Hilla Rebay, this building, and perhaps this museum, would not exist, nor would the unparalleled collection of non-objective art it protects have ever been accumulated. The building is perhaps the most important design by the most influential architect America has ever produced—Frank Lloyd Wright. Hilla Rebay is who asked Wright to design it. Wright once referred to Rebay as a “superwoman,” and is even reported to have said he “built the museum only for her.”

So if Frank Lloyd Wright found so much in Hilla Rebay to adore, why was she hated by so many others? The answer, sadly, may be because she was a confident, strong, aggressive, passionate woman. Her enemies were mostly members of the family of Solomon R. Guggenheim. Chief among them were Irene, his wife, and Peggy, his niece. Irene despised Hilla Rebay because of the rumors that circulated that she was more than just a friend and business partner to Solomon, though in reality there is no evidence that the two were anything more than mutual lovers of art. And jealously may also have been at the heart of why Peggy Guggenheim hated Hilla. Their tenuous relationship is embodied byan irate letter Hilla wrote Peggy regarding the opening of her Art of This Century gallery in 1942, chastising her for associating the Guggenheim name with commercialism in art.

Hilla Rebay - Collage , 1917, 10 1/2 × 17 in, 26.7 × 43.2 cm

Hilla Rebay - Collage , 1917, 10 1/2 × 17 in, 26.7 × 43.2 cm

The Museum of Non-Objective Painting

The reason for the animosity Hilla Rebay directed toward Peggy for opening a commercial art gallery was that just three years earlier Rebay and Solomon Guggenheim had opened up their own modern art exhibition space, known as the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. Located in a rented townhouse at 24 East 54th Street, the space was conceived as a sacred environment dedicated to what Rebay believed could be the salvation of humanity: non-objective visual art. Those who visited the museum when it was located in the townhouse have recalled it smelling of incense and seeming more like a chapel than an art museum. And that was no accident. Rebay believed that the visual language presented in the paintings the museum displayed had the potential to transform relationships and guide humanity on a path toward a higher and more peaceful realm of existence. Therein lied her disagreement with Peggy. Rebay had worked hard to create a safe space for the spiritual in art, and wanted the Guggenheim name to only be associated with the utopian ideals that space represented.

But in reality, the Guggenheim name would prove to be large enough to accommodate both approaches to modern art. The Art of This Century gallery went on to become one of the most influential forces in American abstract art, and today the Peggy Guggenheim Collection is housed in a monumental museum on the banks of the Grand Canal in Venice, Italy. And that spiritual safe space that Hilla Rebay created in a rented townhouse went on to become the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. But the reputation these two influential women earned is quite different. Peggy Guggenheim is widely, and rightfully acknowledged as a pioneering patron of Modern Art. But Hilla Rebay, who recommended the purchase of virtually every item in the Solomon R. Guggenheim collection of non-objective art, gets little credit at all. If you look up the history of the life of Solomon R. Guggenheim, you see he was one of the wealthiest men in America and that he was an art collector. And you may see that the museum that bears his name is regarded as possessing one of the finest collections of non-objective art in the world. But the only mention of Hilla Rebay is that she was his so-called art advisor.

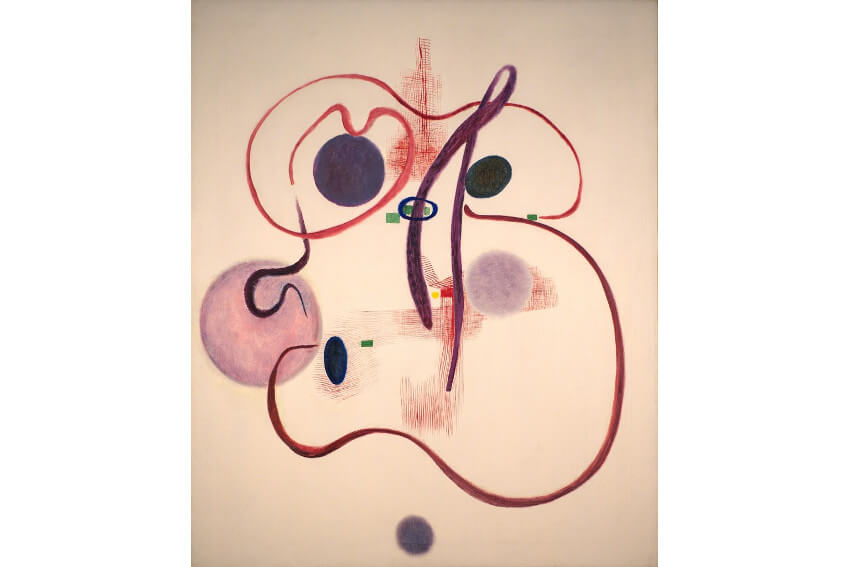

Hilla Rebay - Delicate, 1950, Oil on Canvas, 51 × 42 in, 129.5 × 106.7 cm

Hilla Rebay - Delicate, 1950, Oil on Canvas, 51 × 42 in, 129.5 × 106.7 cm

A Partnership Born

Hilla Rebay came to America in 1927 with the sole intention of spreading the gospel about non-objective art. She mas an artist herself, but acknowledged that her abilities as a painter paled in comparison to her abilities as an art enthusiast. She met Solomon R. Guggenheim at a dinner party in 1928, and offered to paint his portrait. When Guggenheim came to her studio he saw her collection of non-objective art, which she had brought with her from Europe. The collection was composed of works from her friends, who happened to be many of the artists who have now come to be recognized as the most important pioneers of European abstract art. She had works by Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Marc Chagall, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber. And she had a large body of work by her lover, an artist named Rudolf Bauer. Prior to this encounter, Guggenheim did not collect abstract art. But he was so impressed with what he saw, he partnered with Rebay and mounted an intensive effort to acquire all of the abstract work that he could.

Rebay took Solomon to Europe and introduced him to her acquaintances. And yes, she became his art advisor, directing him to buy thousands of artworks. But to diminish her contribution to only that is shameful. It was Hilla, not Solomon, who advocated for the foundation of a museum to exhibit the works. It was Hilla who ultimately pushed for the creation of a permanent building to house that museum. Andit was Hilla who convinced Frank Lloyd Wright to design that building. The influence she had not just over this museum, but over the art world in general, cannot be overstated. Her impeccable taste led to an incredible collection being amassed. And the money she directed Solomon R. Guggenheim to spendsaved some of the most important artists of the era from poverty and obscurity.

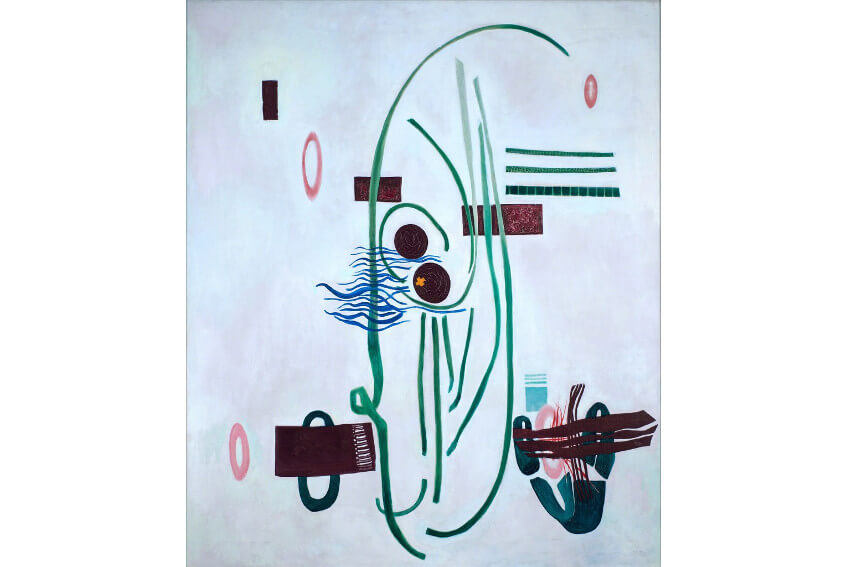

Hilla Rebay - Orange Cross, ca. 1947, Oil on canvas, 44 1/8 × 37 in, 112.1 × 94 cm

Hilla Rebay - Orange Cross, ca. 1947, Oil on canvas, 44 1/8 × 37 in, 112.1 × 94 cm

The Bitter End

Rebay also influenced Guggenheim to sponsor many European artists who needed assistance fleeing Europe after the onset ofWorld War II. One of those artists was Rudolf Bauer, her lover. Rebay not only convinced Guggenheim to sponsor Bauer to come to America, she even arranged for him to provide Bauer with an oceanside villa, a custom car, and a salary for life. She furthermore convinced Guggenheim to collect hundreds of paintings by Bauer, despite the fact that most critics believed then, and still believe now, that Bauer was a hack who was just copying Wassily Kandinsky. Perhaps this was the real reason for the animosity the Guggenheim family felt toward Hilla Rebay: Solomon literally spent a fortune supporting Bauer, and none of that money is likely ever to be recouped.

Nonetheless, Hilla Rebay deserves respect. She founded the Museum of Non-Objective Art, and until 1952, the year Solomon Guggenheim died, was its director. It is a shame that most people have no idea how important that accomplishment was, because the first order of business his family undertook when Solomon died was to change the name of the museum to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and the second order of business was to fire Rebay. By the time Frank Lloyd Wright finished building his temple to non-objective art, which would permanently house the collection Solomon R. Guggenheim left behind, the feud between the Guggenheim family Hilla Rebay was set in stone. They forbid Rebay to attend the opening, andit is believedthat she died having never stepped foot in the building. But it is a precious gift to the rest of us to have the opportunity to enjoy the fruits of her labor. So this year, as we mark the 50th anniversary of her death, we should take moment to remember the visionary Hilla Rebay: an overlooked, but essential patron in the history of abstract art.

Featured image: Hilla Rebay - Composition #9 (detail), 1916, Oil on panel

All images credits Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco, all images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio