Was Hilma af Klint the Mother of Abstraction?

The first time most people heard the name Hilma af Klint was in 1986, when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art included her work in an exhibition titled The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985. The mission of this ambitious show was to investigate the mystical, spiritual and occultist movements that emerged in western society around the end of the 19th Century, and to elucidate their influence on the evolution of abstract art. The show was divided in two parts. One explored themes, such as Cosmic Imagery, Synesthesia, and Sacred Geometry, as examined through the work of many different artists. The other dealt with the work of five specific artists considered by the curators to have been pioneers of spiritual abstract painting. The first four pioneers were well-known artists: Wassily Kandinsky, František Kupka, Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian; revered giants considered by almost everyone to be the inventors of modern abstraction. But the fifth was a total unknown—a new discovery: Hilma af Klint. A Swedish mystic and medium, Klint had evidently developed her seemingly abstract visual language years before the others, at least as early as 1906. Not only that, but she had apparently done it in total isolation from the social and professional circles connected with early Modernist art. Her presence in the show was shocking. It rewrote the origin story of western abstract painting. Since that exhibition, Hilma af Klint has received much attention, both from viewers fascinated by her imagery and from academicians hoping to verify the timing and validity of her aesthetic discoveries. So who was this mysterious artist? What compelled her to make such work? And was she really the mother of abstraction? More than 30 years after her rediscovery, the answers remain unclear.

A Polarizing Force

When The Spiritual in Art exhibition first opened it was immediately controversial—not only because of the inclusion of Hilma af Klint, the apparently overlooked inventor of abstract painting, but also because of the notion it seemed to put forward that abstract art is inherently spiritual. That assertion was not new. At risk of oversimplifying, there are several different ways to approach abstract art. Many people see it as spiritual, or at least as a potential medium for contemplation: something to look at while letting the mind, heart and spirit make their own inquiries. But many other people prefer to deal with it in purely formal terms: appreciating its aesthetic elements without delving into questions of meaning or content. Still others enjoy attempting to decode it on a secular level: assigning subjective values to its imagery, or lack thereof, in an effort to “figure it out.”

Generally it is in the interest of everyone involved, from the artists to the curators to the sales people, for viewers to be allowed, even encouraged to make up their own minds about such things. After all, is not the entire point of abstraction to open the door to a wider range of possibilities? But by staging The Spiritual in Art exhibition, the curators, and by extension LACMA, seemed to be making the definitive statement that abstract art is, without question, rooted in the divine. And by including abstract artists of every generation up to contemporary times, they were furthermore arguing that the spiritual tradition of abstraction continues to be a vital and important force.

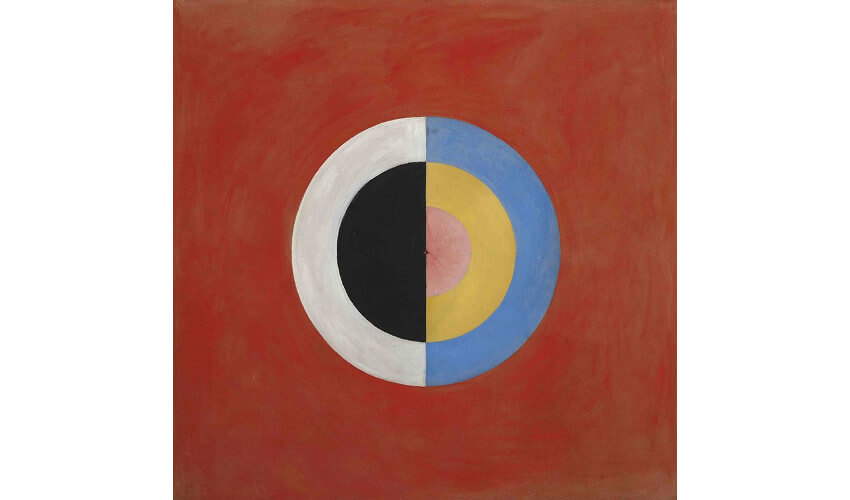

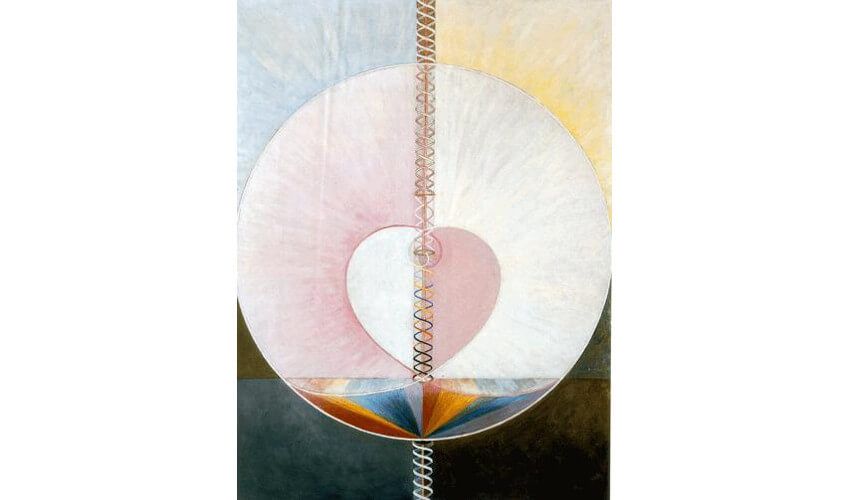

Hilma af Klint - Group IX/SUW, No. 17. The Swan, No. 17, 1914-5, Oil on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk, photo Moderna Museet / Stockholm

Hilma af Klint - Group IX/SUW, No. 17. The Swan, No. 17, 1914-5, Oil on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk, photo Moderna Museet / Stockholm

Down the Rabbit Hole

Despite the fact that Hilma af Klint was the least known of all of the artists included in The Spiritual in Art exhibition, she nonetheless was the most divisive. The reason has less to do with her spirituality than with whether or not her work is actually abstract. Every shape, every line, every scrawl and every color in each of her spiritual paintings was intended to be symbolic. The paintings are rife with hidden narratives waiting to be decoded. They contain the symbology of a hidden spiritual world to which Klint claimed to have special access. Wassily Kandinsky wrote in detail about his quest to connect with universalities through abstraction, and he was clear that his inquiries were made in a spiritual vein. But he was also clear that he was not being symbolic, and there were no hidden narratives in his work. It was purely non-representational. And the same can be said for Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian.

But Klint took symbolism in art to a new extreme. She was a founding member of a group called The Five, which held séances in an effort to connect with the Höga Mästare, or High Masters. Her beliefs were informed by Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, founder of the Theosophical Society, a non-sectarian spiritual community interested in forming “a nucleus of the universal brotherhood of humanity,” and investigating “the unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in man.” In her book The Secret Doctrin, written in 1888, Madame Blavatsky asserted that a master race of spiritual beings was guiding human evolution: the same beings Klint claimed to connect with while painting. Also tied to Madame Blavatsky were Rudolph Steiner, creator of the Anthroposophical Society, and Charles Webster Leadbeater, the discoverer, some would say brainwasher, of Jiddu Krishnamurti, who was convinced in 1909, as a child, that he was the Maitreya, or World Teacher, believed by Theosophists to be the reincarnation of Christ.

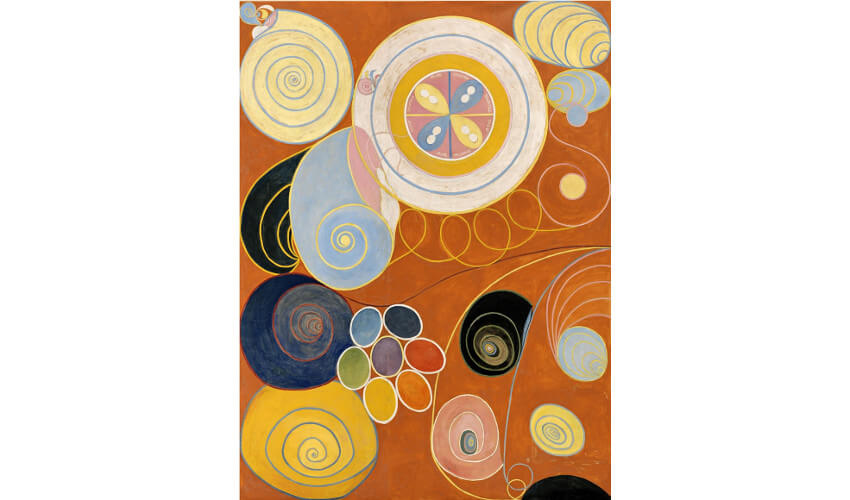

Hilma af Klint - Group IV, No. 3. The Ten Largest, Youth, 1907, Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk, photo Moderna Museet / Stockholm

Hilma af Klint - Group IV, No. 3. The Ten Largest, Youth, 1907, Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk, photo Moderna Museet / Stockholm

Splitting Heirs

Prior to joining The Five, Hilma af Klint was a trained figurative artist. She studied at the Technical School in Stockholm, and later at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. After graduating in 1887, she made a living painting realistic landscapes and portraits. She only made the transition to what we now call her abstract style after making her connection with spiritualism. But again, the question is whether we should call her spiritualist paintings abstract. Certainly their visual language of squiggles, swirls, circles and coils is similar to that of the paintings of Kandinsky and others. But there is something fundamentally different about the reasons Klint made these marks. She believed that when she painted she was directly transcribing the mysterious symbols of the spirit world.

Kandinsky, Malevich and Mondrian were motivated by their own intellectual journeys toward non-representational art. They wanted viewers to look at their work and find some personal connection with the unseen. They wanted their paintings to correlate to something universal, beyond the meanings of the everyday world, but they were not being symbolic: quite the opposite. They were being intentionally un-symbolic. Klint was not involved in an intellectual pursuit of universalities. She claimed to be transcribing a secret visual code communicated privately to her by a master race of spiritual beings. She intended her paintings to be used not as tools for personal contemplation, but as tools for understanding specific directives from beyond, which for those able to translate them might offer secret knowledge.

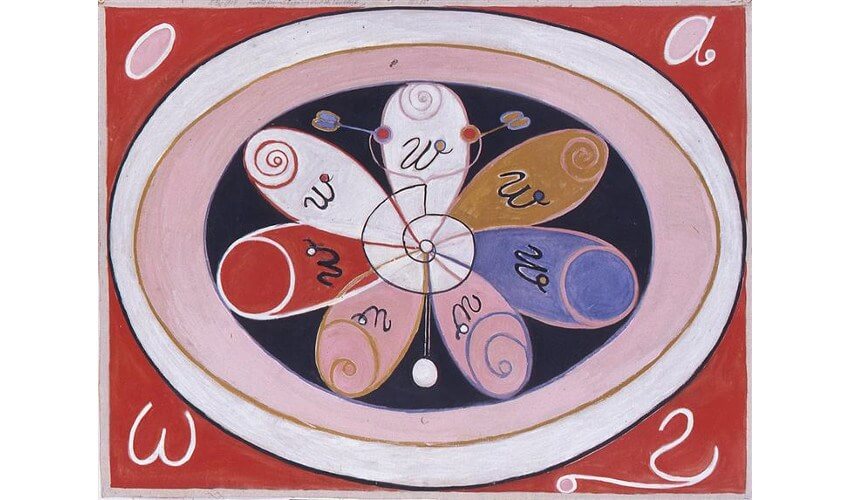

Hilma af Klint - Untitled

Hilma af Klint - Untitled

The Original X-Files

It is worth mentioning that Madame Blavatsky was once investigated by the non-profit Society for Psychical Research, a group founded in London in 1882 dedicated to researching paranormal phenomena. Their report concluded that Blavatsky was, “one of the most accomplished, ingenious, and interesting impostors in history.” They described the numerous tricks she used to fool participants in her séances, and in general presented a picture of her, the Theosophical Society and its offshoots as being fraudulent.

What does that mean for Hilma af Klint? It could mean she was part of the fraud, and was making strange paintings intended to convince others she had a connection to the beyond that she simply did not have. Or it could mean she was deluded after being misled by other members of the group. Or it could mean neither of those things. Perhaps Hilma af Klint truly did feel a connection with an unknown power, which in turn informed the imagery in her paintings. Perhaps it was not a divine power but her subconscious. Her process was remarkably similar to the automatic drawing experiments of the Surrealists. Perhaps she simply had a different understanding about where those impulses were coming from, and what, if anything, they might mean.

Hilma af Klint - The Ten Largest, No. 6 Adulthood, Group IV, 1907, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint - The Ten Largest, No. 6 Adulthood, Group IV, 1907, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Formalist Readings of the Divine

If we were simply to stumble upon the spiritual paintings of Hilma af Klint without knowing their back story it would be easy to classify them as abstract, and to give them their due place alongside works of the other important pioneers of Modernist abstraction. In a straightforward formalist critique there would certainly be much to say. She could be seen as a conceptual pioneer of the use of calligraphic markings, and the use of text in painting. We could discuss how she flattened the picture plane, and how she treated color only as color, shape only as shape, and line only as line, elevating each of the formal elements of art to the level of subject matter.

We could also talk about how her paintings seem to have prefigured many early Modernist tendencies, such as Orphism, Lyrical Abstraction and biomorphism. And even if we do first acknowledge the alleged spiritual origins of her technique, we can still give her credit for prefiguring many of the ideas that influenced Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and perhaps many more Modernist positions. Indeed, when interpreted on this level, Hilma af Klint deserves to be recognized as the mother of abstraction, and as one of the Grand Dames of Modernism.

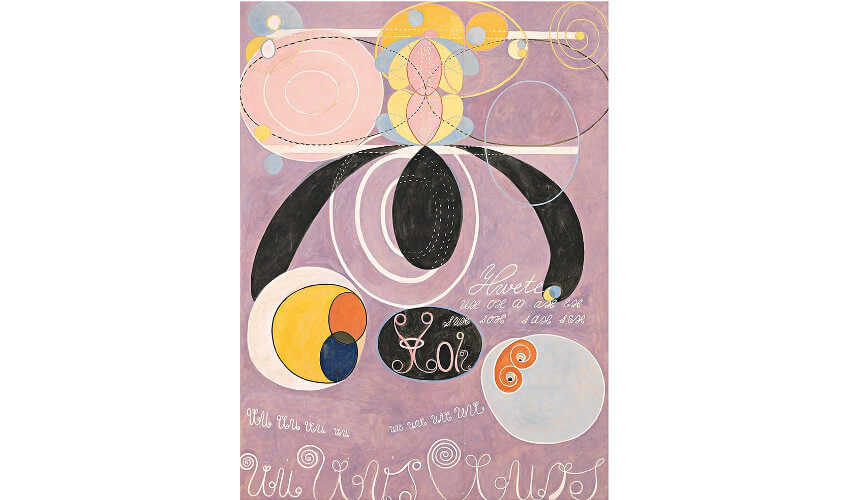

Hilma af Klint - What a Human Being Is, 1910

Hilma af Klint - What a Human Being Is, 1910

The Full Measure

But we are obliged not to solely consider the work of Hilma af Klint from a formalist perspective. We are obliged to take the full measure of her work. And when we do this, we must be honest and admit she does not belong in the company of Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian and the others. There are several reasons why. The most pessimistic, perhaps cynical reason is that she may have made these paintings to intentionally deceive people. Theosophists have a well-documented track record of chicanery. Consider the fact that Klint never exhibited her abstract paintings to anyone from the art world during her life. And when she died in 1944, her directive to her estate was for her nephew, Erik af Klint, not to exhibit her works for a minimum of 20 more years.

Why go to such lengths not to share her work with the world? Why would the sole recipient of divine messages from a master race of spiritual beings, whose secret wisdom had the potential to unite humankind, not share it with everyone? Why share it only with those who already believe? Perhaps she was simply afraid she would be mocked. Or perhaps she was a liar, or insane. But regardless, there is another, more obvious reason she does not deserve to be included among those other pioneers of abstraction, and that has to do with intent. Each of those others—Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian, et al.—was intent on creating something original. Assuming she was not insane, a liar, or a fraud, by her own admission Klint was taking dictation. Her intent was not to be abstract. Her intent was to communicate precisely what the hidden spiritual masters were telling her to communicate. That is as representational as painting gets.

Featured image: Installation view from Hilma af Klint: Painting the Unseen, Serpentine Gallery, London, 2016, Image © Jerry Hardman-Jones

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio