Hsiao Chin - Pushing the Limits of Abstraction

As a young art student in Taiwan in the 1940s, Hsiao Chin received advice from his teacher regarding the responsibility of an artist, which went something like this: an artist must find a personal way to express their historic tradition, while also connecting it somehow with the global trends. In other words: artists build bridges. In order to accomplish this not-at-all-simple feat, Hsiao banded together with a small group of his schoolmates to form what is considered the first abstract art collective in China: the Ton-Fan Group. Ton-Fan means Eastern, which was not meant to limit the members of the group, but rather implied that these artists saw themselves as an Eastern contingent of a global movement towards a more openminded approach to modern art. For Hsiao, this literally meant leaving Taiwan to experience first hand what artists in other places were doing and thinking. He spent decades living in the West, co-founding several more art movements along the way, such as Movement Punto, the Surya Movement, and the Shaki Movement, which each included artists from all over the world. To his surprise, it was an experience in Italy that made Hsiao fully aware of his own native art traditions. Seeing contemporary European art during a visit to the Venice Biennale taught him how presciently ancient Chinese art forms predicted the achievements of Western Modernism. This realization led him to develop his own unique aesthetic voice, which combines elements of Chinese symbolism, Tibetan Buddhist color theories, and the methods of Western Abstraction. In celebration of his 85th birthday in 2020, the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Latvia opened a Hsiao retrospective, juxtaposing six decades of his work with paintings by Rothko, whom Hsiao befriended while visiting the United States in the 1960s. The exhibition proves that Hsiao has not only built bridges between the past and present, and between his culture and the rest of the world: he has succeeded in connecting Earth with the universe at large.

Filling the Void

It is clear from the writings Rothko left behind that he and Hsiao share certain spiritual aspirations for their art. However, the Western abstract artist whose work I think most visually resembles the work of Hsiao is Adolph Gottlieb. With their gestural brush marks, circles, and biomorphic color blobs, the most famous Gottlieb compositions, such as “Trinity” (1962), which is in the permanent collection of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, could easily be confused for Hsiao paintings. However, Gottleb and Hsiao could not be more different when it comes to the intent. Gottlieb once said, “If I made a serpentine line it was because I wanted a serpentine line. Afterwards it would suggest a snake but when I made it, it did not suggest anything. It was purely shape.” Hsiao, on the contrary, fully intended for the shapes and lines in his paintings to be symbolic.

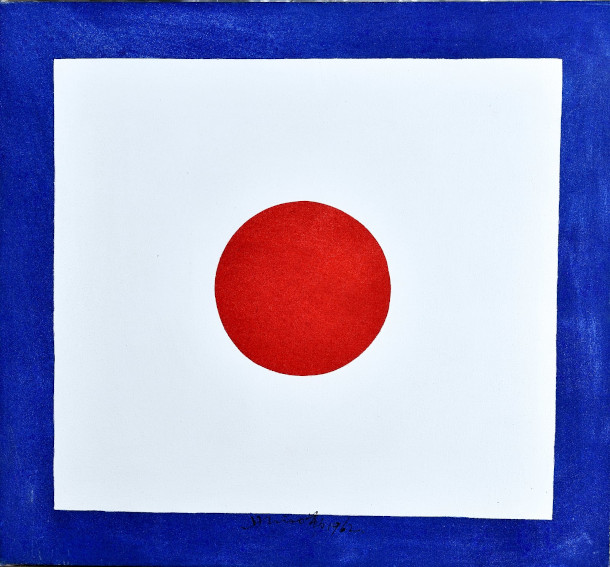

Hsiao Chin - Tao, 1962. Acrylic on canvas. 64 x 69 cm. © Hsiao Chin

In a Hsiao painting, serpentine lines might be interpreted as expressions of spirit breath, or chi; circles might express oneness, or the endless expanse of the sky; rectangles might represent Earth, or perhaps another planet. The most powerful difference between how Gottlieb and Hsiao perceived aesthetic intent, however, will not be found in the parts of the canvas they painted, but in the parts they did not paint. To Hsiao, a void is a symbol of creative potential—the source of all being. To Gottlieb, a void was purely a compositional device referencing nothing but itself—the absence of being. The difference is subtle, and maybe better left to philosophers. However, going back to the comparison between Rothko and Hsiao, we can see that even though both of these artists were indeed trying to achieve something spiritual through their paintings, only one of them—Rothko—entirely covered his surfaces in paint, apparently feeling compelled to fill even his voids with substance.

Hsiao Chin - Untitled, 1962. Acrylic on canvas. 114.5 x 146.5 cm. © Hsiao Chin

Points of Origin

One of the most memorable stories Hsiao has shared about his life is that while he was living in Turin, Italy, he was friends with a woman who claimed to be receiving weekly telepathic messages from inhabitants of alien planets. She shared her messages with Hsiao, who completely accepted them as evidence that we are all part of something much more expansive and varied than our daily lives on this planet might lead us to think. Even after her death, Hsiao attempted to continue communicating with this friend through a medium—attempts Hsiao considers successful. Both his “Dancing Lights” series from the 1960s, and the series of paintings he made after the death of his daughter in the 1990s, poignantly express his belief in the vastness of spirit energy that exists in the universe, and the multitude of life that exists beyond us, beyond our planet, and beyond our limited experience of reality.

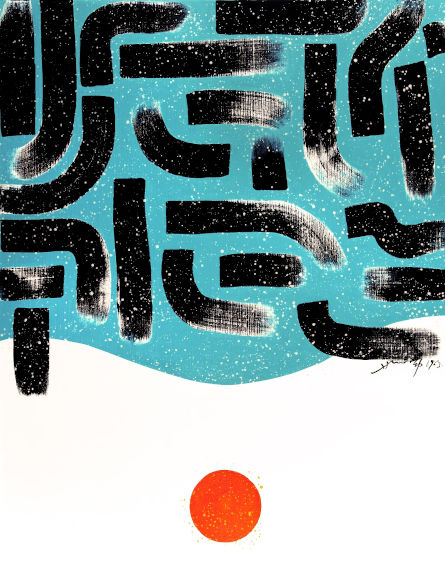

Hsiao Chin - Dancing Light 15, 1963. Acrylic on canvas. 140 x 110 cm. © Hsiao Chin

Without a trace of irony or self-awareness, Hsiao liberally references his belief in extraterrestrial lifeforms and the spirit world right along side everything from Taoism, mandalas, Buddhist tantric paintings, and Chinese ink painting, to Abstract Expressionism, Post Painterly Abstraction, Minimalism, and Color Field Painting. He paints his own experiences with death, life, grief, and love, and sees no contradiction between those topics and the goals of contemporary abstraction. The beauty of his guiding philosophy was perhaps best expressed in the name he gave to the art movement he co-founded while living in Milan in the 1960s: Movimento Punto. Punto is an Italian word for point. You could read it as a reference to the circles Hsiao puts in his paintings, which are, in a way, points. Spiritually, they symbolize mystery, and non-being; formally they are the very manifestation of the beginning of being: points beget lines, which beget planes, shapes and forms, which give way to color, depth, and perspective. With this one symbol, Hsiao proves there is no separation between his progression as an artist and as a human: to me, this is the most important bridge he has built.

Featured image: Hsiao Chin - Dancing Light 19, 1964. Acrylic on canvas. 110 x 140 cm. © Hsiao Chin

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio