The Guggenheim Presents: Jackson Pollock's Mural

One of the most storied American paintings is returning to Manhattan after a 22-year absence. “Mural” (1943) by Jackson Pollock will be on view at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York from 3 October 2020 through 19 September 2021. The “focused exhibition” (meaning it is the only picture in the show) is the latest stop on a six-year world tour the painting has been on since its two-year long cleaning and conservation at the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles. The reconditioned 345-pound, 2.5 x 6 meter painting made its debut in 2015, in the exhibition Jackson Pollock’s Mural: Energy Made Visible, at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, Italy. Since then it has travelled to museums in Berlin, Málaga, London, Kansas City, Washington, DC, and Boston, among others. Following its upcoming stay in New York, “Mural” will return to what is technically its permanent residence: The University of Iowa Museum of Art. (Peggy Guggenheim gifted the painting to the Hawkeyes in 1951, allegedly after students at Yale, her first choice, declined the offer.) Manhattan, however, will always be able to stake its claim as the true home of “Mural.” Pollock painted it in his Lower Manhattan studio after being commissioned by Guggenheim to create a work to hang in the long, narrow foyer of the apartment building where she lived on East Sixty-first Street. This commission is what enabled Pollock to transition from his day job as a conservator at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting to being a full-time artist. Much has already been written about the landmark achievement in abstraction that “Mural” represents, as well as the various myths attached to the work, such as the now debunked claim that Pollock painted it in a single day. As part of our preparations for the New York homecoming of this landmark painting, we thought we would take a look at two other important aspects of the work, such as an overlooked photographer who helped inspired Pollock to create his gestural painting style, and the lasting aesthetic legacy “Mural” helped define.

Lights in Action

You may have already heard the story of how some methods for which Pollock is now renowned were actually pioneered by the renowned Mexican Muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. Pollock took classes from Siqueiros in the 1930s, during which the students were taught to generate emotional power in their compositions by splashing and splattering paint onto their surfaces. However, there is only sparse evidence of dripping and splashing in “Mural,” which is considered the first “all-over” abstract painting Pollock created. Contemporary scientific analyses reveals that most of the marks in the painting were made by a traditional brush making direct contact with the canvas. “Mural” does, however, represent a breakthrough moment for Pollock in terms of another technique: his use of gestural mark making. The composition is frenetic and biomorphic: a jungle of flowing, gestural lines and forms. Films of Pollock at work in his studio later in life show how he employed his entire body, like a dancer, so that his paintings would become embodiments of energy and action.

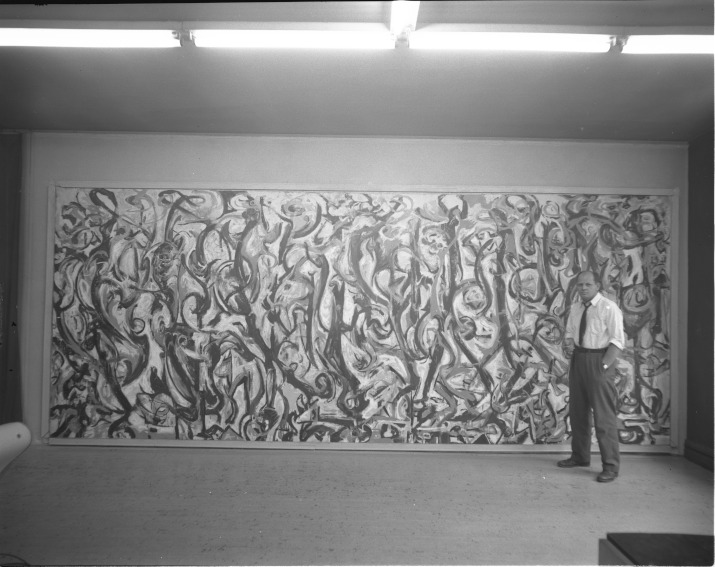

Jackson Pollock standing in front of Mural (1943) at the studios of Vogue magazine, ca. 1947. Photo: Herbert Matter, courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Of course, gestural movements have always been part of the painterly tradition. Chinese ink artists harnessed the emotive potential of painted gestures centuries ago. “Mural” is nonetheless considered a forbearer of a distinctly contemporary movement called “action painting.” Pollock is a pioneer of this movement, yet his gestural methods were also inspired by the work of another artist—a photographer named Barbara Morgan. An early advocate for the potential for abstraction within the photographic medium, Morgan first made her name photographing modern dancers in New York City in the 1930s. Inspired by the fluidity of their movements, she started creating what she called “light drawings” around 1940. She would set her camera up with its aperture open in a dark room, and then use a hand-held light to “draw” on the negative while performing gestural movements. These gestural, abstract light drawings bear a notable resemblance to the lines and forms in “Mural.” This takes nothing away from Pollock, of course—it is just an acknowledgement that that he was familiar with Morgan and her light drawings, which were included in the exhibition Action Photography at MoMA the same year Pollock painted “Mural.”

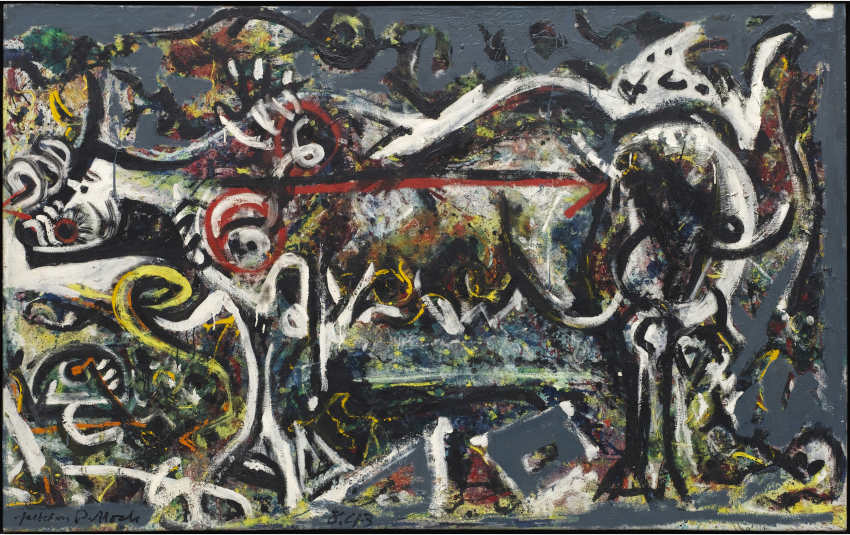

Jackson Pollock, The She-Wolf, 1943. Oil, gouache, and plaster on canvas, 106.4 x 170.2 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Purchase, 1944 © 2020 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York

Representing Nature

Though “Mural” is considered abstract, some figurative content is also visible within the composition. Pollock once described the picture as containing, “a stampede [of] every animal in the American West, cows and horses and antelopes and buffaloes.” Some say a horse head is clearly evident just to the left of center in the composition. Nevertheless, the lasting impact Pollock has had on the evolution of modern art has nothing to do with whatever narrative content a viewer might perceive in this, or any of his other paintings. Rather, his legacy has to do with the way he painted. It can be summed up by his famous response to the question once posed to him, of whether he paints from nature, to which Pollock responded, “I am nature.”

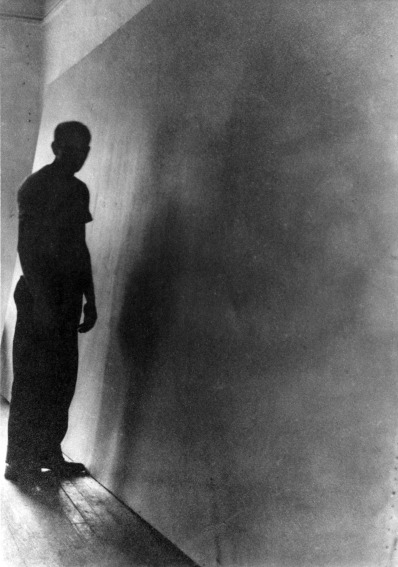

Jackson Pollock with the unpainted canvas for Mural in his and Lee Krasner’s Eighth Street apartment, New York, summer 1943. Photo: Bernard Schardt, Courtesy Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, East Hampton, New York, Gift of Jeffrey Potter

Pollock grasped the conceptual notion that the true subject of a work of visual art need not be contained within any visual aspect of the art itself. He made the leap from being an artist who represented nature in pictures to being an artist who is a living representative of nature. The positions of artists as diverse in their aesthetic approach as Yves Klein, Joseph Beuys, the Gutai Group, Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, Alan Kaprow, Donald Judd, Richard Tuttle, and Carolee Schneemann, are all rooted in this same anti-materialist notion, that the aesthetic relic is less important than the creative act itself. This is an under appreciated aspect of the Pollock legacy, perhaps because his artworks are among the most expensive material things on Earth. I nonetheless consider it the most important thing he proved: that method is meaning.

Featured image: Jackson Pollock - Mural, 1943. Oil and casein on canvas, 242.9 x 603.9 cm. University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art, Gift of Peggy Guggenheim, 1959.6 © 2020 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio