James Stanford's Shimmering Zen of the Mandala

Jun 25, 2018

As a child, James Stanford had little experience with fine art. He was born in Las Vegas in 1948, 13 years after gambling was legalized in the city, and three years before the U.S. Government began testing nuclear bombs in the surrounding desert. The fledgling City of Sin boasted plenty of risks at that time, and plenty of distractions, but one thing it did not offer was an art museum. In fact, the first museum Stanford ever visited was the Prado, in Madrid, Spain, at age 20. He recalls that visit as his first experience ever with fine art, and says that it was a personal religious experience. Stanford describes standing in front of a painting called “Deposition,” by the 15th Century, Netherlandish Mannerist painter Rogier van der Weyden, and admiring the intricate technique the artist had used to outline the figures in the painting, which made them seem to float outward from the rest of the scene. As he stood staring deeply at the surface of the painting, he fainted. He was unconscious for 15 minutes. When he awoke, he reported having “a flash grasp of many of the painting techniques” that van der Weyden used to create the painting. “This started my devotion to painting,” says Stanford. “To me, it is part of my personal religion.” Today, it is Stanford whose works inspire quasi-religious experiences in viewers. Still living and working in the atomic neon desert of Las Vegas, he has become a contemporary ambassador for the ancient notion that there is an intrinsic connection between spirituality and art.

Calculating the Incalculable

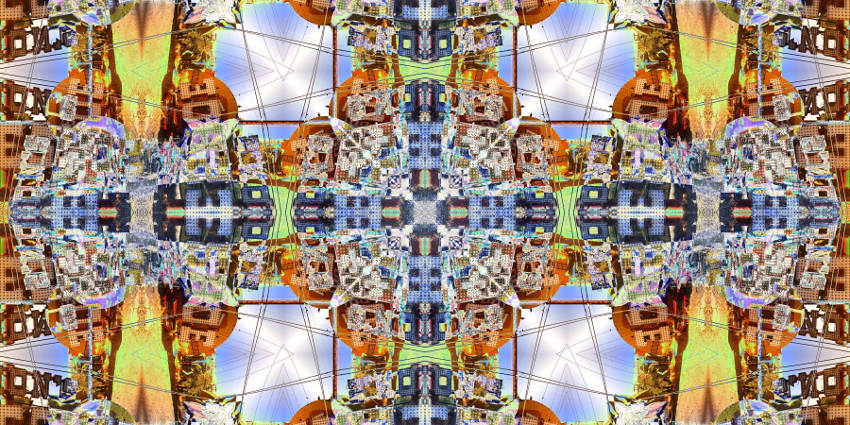

The body of work by Stanford that most directly expresses his belief in the spiritual potential of art is his series of digital photographic montages, which he calls “Indra’s Jewels.” Although he describes these works as completely abstract, they contain fragments of many figurative images, and they take their inspiration from narrative Hindu / Buddhist aesthetic traditions. In Book 30 of a nearly 2000-year old East Asian text called the Avatamsaka Sutra, it is written that “the cosmos is unutterably infinite, and hence so is the total scope and detail of knowledge.” The book is also known as The Incalculable because of its focus is on the subject of infinitude. Incalculable infinitude is what Stanford is attempting to express with his “Indra’s Jewels.” He borrowed the title from the story of Indra, a Vedic Hindu deity who is often compared to Zeus. According to legend, a net hangs over the palace where Indra lives. This net contains a jewel at every connective point. Every jewel is reflected in every other jewel—a metaphor for the interconnectedness of all things.

James Stanford - Shimmering Zen - Flamingo Hilton. © James Stanford

Pictorially, Stanford designs his “Indra’s Jewels” based on the design principals of ancient Hindu and Buddhist pictures called mandalas. The prefix “manda” means essence, and the suffix “la” means container. The mandala is therefore considered to be an essence container—a manifestation of totality. Visually, mandalas are geometric and contain a mixture of figurative and abstract imagery. They usually take the form of a square with an inner circle, which itself contains additional squares. At the center of the composition should be a dot, representing the original creative force, the primordial container of the essence of infinite totality. Mandalas are considered art, and they are also considered to be meditative tools. Those who create them are trained for many years in both artistic technique and spiritual tradition. Like Hindu and Buddhist mandalas, Stanford intends for his “Indra's Jewels” to be appreciated for their beauty as well as for the wisdom they may reveal, which theoretically may have the potential to aide viewers in their quest for enlightenment.

James Stanford - Binions V-1. © James Stanford

Infinite Light

To create his re-imagined, contemporary mandalas, Stanford turns to the signs and symbols representing the deities of Las Vegas—casinos, hotels, and bars. He photographs their historic neon facades, and Googie architectural elements, cropping various bits and pieces from the photos, which he then uses as the building blocks for geometrically repeating patterns. The center dot for his compositions is not a deity, but rather a visual focus point from whence the shapes, lines, colors, and patterns—building blocks of abstract art—evolve. Metaphorically, the images Stanford appropriates for these compositions relate back to a nostalgic starting point when his own life was beginning. By cropping and digitally altering the source photographs he is rearranging their essential elements, shattering them like jewels whose infinite shards now might reflect each other forever into time and space.

James Stanford - Shimmering Zen - Awaz. © James Stanford

There are as many questions hiding within the works Stanford makes as there are in traditional mandalas. Are viewers supposed to meditate on these pictures? Should we contemplate the associations sparked by the glimpses of signs and symbols? Are the extremes of light and darkness important? Or are these questions really only distractions, keeping us from understanding the true message of the mandala? One source of guidance for how to read these fascinating and unique artworks can be found in the single design element they actually do share with traditional Hindu and Buddhist mandalas: their dependence on perspective. If you were to lay these pictures flat on the ground and then look at them from one perspective, the images closest to you would be upside down. The images farthest away would be right side up. The images to the left and right would be askew. Only if you stood on the center of the picture and turned to face each direction one at a time would the various perspectives begin to look the same. Somewhere in this aspect of the work is a lesson, perhaps. Stanford is sharing with us the notion that in both art and spirituality, the most important thing is to look, and to realize that there are many different ways to see something. What you think is real simply depends on where you stand.

Featured image: James Stanford - Lucky Lady. © James Stanford

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio