Dansaekhwa Korean Painting - A New Trend in Abstract Art

May 11, 2016

Many different paths lead to the same destination. Throughout humanity’s history of making art, various impetuses have caused painters to engage in what we might call the urge to simplify, or to pare down the visual language. Dansaekhwa is the name given to one such trend in Korean painting that emerged in the 1970s. At that time, Korea’s culture was finally flourishing again after decades of war. Korean painters sought to connect with something ancient and pure, something beyond the suffering their society had been enduring. Dansaekhwa was their method. The word translates roughly into “monochrome painting,” but the paintings associated with the movement aren’t monochrome so much as they’re neutral and subdued. The real heart of Dansaekhwa is that the artists associated with it denied themselves a subject, a choice that required them to build their images up from nothing and to discover them as they were revealed.

Korean Painting vs. Western Minimalism

Perhaps in the West we tend to take for granted that the Western art world inspires all global art trends. So when we notice that artists from another culture seem to be making art that looks similar to something Western artists have done or are doing, we assume those artists from that other culture are imitating our ways. This phenomenon is happening now as the Western art world is becoming aware of Dansaekhwa.

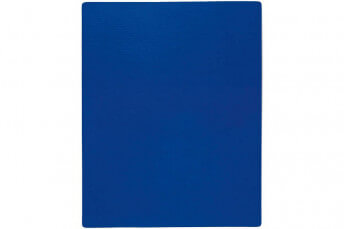

Westerners notice the subdued color palette of Dansaekhwa paintings and then hear that Dansaekhwa means monochrome and they immediately assume that the Koreans are copying Yves Klein, Ellsworth Kelly, Gerhard Richter or Brice Marden. Westerners hear that Dansaekhwa emerged in the 1970s and they assume that earlier Western concepts such as Donald Judd’s “Specific Objects” must have influenced the trend. And while yes, Dansaekhwa artists and Western Minimalist artists do seem to have arrived at a similar place, the path they took to get there couldn’t be more different.

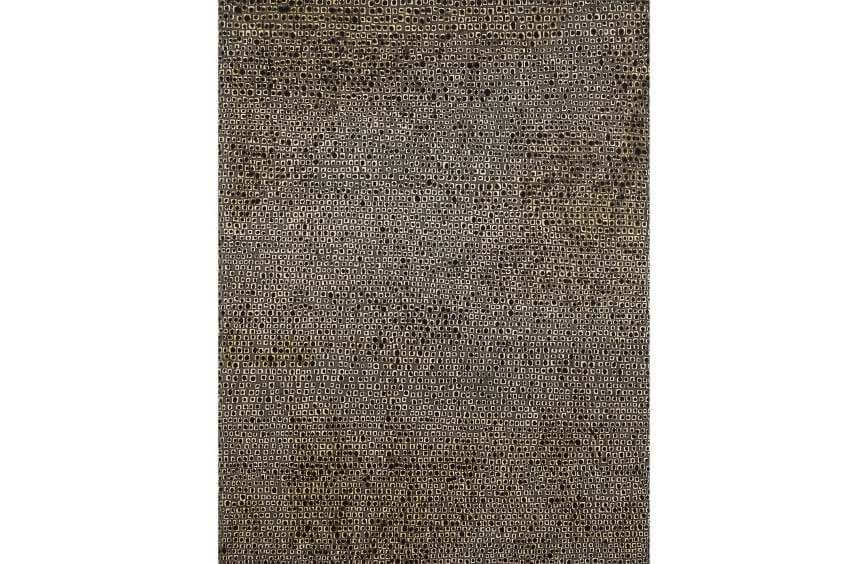

Kim Whan-ki - Untitled, 1970, Oil on canvas, 222 x 170.5 cm, © Kim Whan-ki

The View From Here

While it’s true that many paths do lead to the same destination, the path one takes can profoundly affect one’s perception of the destination upon arriving. At first glance, Dansaekhwa appears to be the same destination Westerners arrived at with Minimalism. The paintings possess a similar aesthetic, a similar palette, and seem to communicate a similar message to the viewer. But Minimalism and Dansaekhwa followed very different paths to this place of simplifying and paring down. An awareness of those different paths causes a very different reading of the two kinds of works.

Minimalism evolved as a reaction against art’s past. Dansaekhwa evolved out of a desire to embrace the past, to return to the roots of society’s relationship with nature. Minimalist art comes about through a process of abstract reductionism, as things are taken away and expressed in flattened terms. Dansaekhwa art comes about through a process of building up and layering as things are accumulated and expressed through repetitive patterns. In Western art, Monochrome paintings are normally comprised of a single hue. Dansaekhwa’s concept of Monochrome is to work with the entire range of a particular hue, exploring the ways it’s affected by light and darkness, texture, materials and other forces. In short, Minimalism subtracts. Dansaekhwa adds.

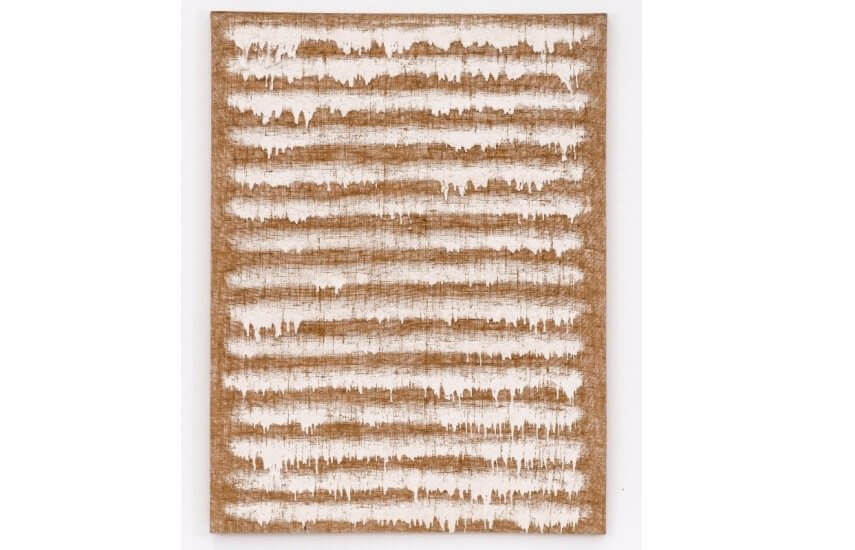

Ha Chong-Hyun - Work 74-06, 1974, Oil on hemp, 60 3/8 x 45 3/4 inches, © Ha Chong-Hyun

Industrial vs. Natural Processes

Another key difference between reductive Minimalist painting and Dansaekhwa is in the notion of process. One of the key tenets of Donald Judd’s “Specific Objects” was the use of an industrial process. Judd was manufacturing things. The human and mechanical elements were both integral to the outcome. Dansaekhwa focuses on natural processes. Although it sometimes incorporates synthetic materials, it represents a return to natural elements, natural textures and the natural roots from whence humans came.

Dansaekhwa is not a rejection of Korea’s, or humanity’s past. It is an attempt to return to something universal, something shared by all members of the natural world. Whereas Western Minimalist artists focused on finishing up with something minimal, Dansaekhwa artists focus on beginning with something minimal and building up from there, while retaining the essential element of simplicity. A Dansaekhwa painting builds like stalactites in a cave, accumulates like ash from a volcano or soot from a forest fire, or morphs into its form like a coral reef.

Kwon Young-Woo - P80-103, 1980, Korean paper on rag board mounted on panel, 162.6 x 129.5 cm, © Kwon Young-Woo

The Only Constant is Change

The key tenets of Dansaekhwa are energy, nature, materiality, tactility, softness, texture, repetition, natural elements such as coal, powder, iron and pigment, and natural surfaces such as canvas and board. In some later Dansaekhwa works the inclusion of synthetic materials such as sequins, steel, plastic and Plexiglas seems to express notions of human culture’s inclusion into the natural world.

Much the same as natural aesthetic phenomena, Dansaekhwa paintings and sculptures seem never to be finished. They could be ongoing, they could keep growing and changing, or perhaps they could suddenly deconstruct, dissolve or disappear before our eyes. A Judd sculpture is an expression of finality. An Agnes Martin painting is organized and complete. An Yves Klein sponge sculpture is a finished product: a fixed object intended never to change. To Dansaekhwa, the notion of change and the possibility of continued evolution are integral to the work, and central to the harmonious message it offers us when we listen.

Featured Image: Ha Chong-Hyun - Work 77-15, 1977, Mixed media, 129 x 167.3 cm. © Ha Chong-Hyun

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio