How Monochrome Paintings of Yves Klein Shifted the Focus in Art

Labels are relative. When a painter paints perfect likenesses of trees and boats and mountains, most people call those paintings representational, because they supposedly represent reality. When a painter paints monochrome paintings and gives them titles like “Tree,” “Boat,” and “Mountain,” most people call those paintings abstract, because they supposedly don’t represent reality. But which art is representational and which is abstract depends entirely on what you perceive reality to be. Through his monochrome paintings, the artist Yves Klein proposed alternative views on reality. Klein’s vision established him as the leader in a movement called Nouveau Réalisme, which focused the art world onto “new ways of perceiving the real.”

Excuse Me While I Sign the Sky

An oft-recounted story about the 19-year old Yves Klein basically sums up the artist’s entire approach to his work. The story goes Klein was sitting on the beach one day in 1949 with Armand Fernandez (who became the artist Arman ) and Claude Pascal (who became a world-famous composer). The three had traveled Europe together and become close friends. While sitting in the sand staring out at the water, they decided to divide up creation between them. Claude Pascal is said to have chosen words; Armand Fernandez took dominion over earth; Yves Klein selected for himself “the void,” what we would now call “dark matter,” the empty—yet not empty—space that surrounds the planet.

Klein allegedly then reached his finger out and signed his name to the sky. The essence of his beach declaration: to explore not only what’s perceptible, but also what appears to be absent, and to assign equal importance to both. That same year, Klein began making monochrome paintings, while simultaneously working on a musical arrangement called the “Monotone Silence Symphony,” which consisted of a single chord sustained for 20 minutes, followed by an equal amount of silence.

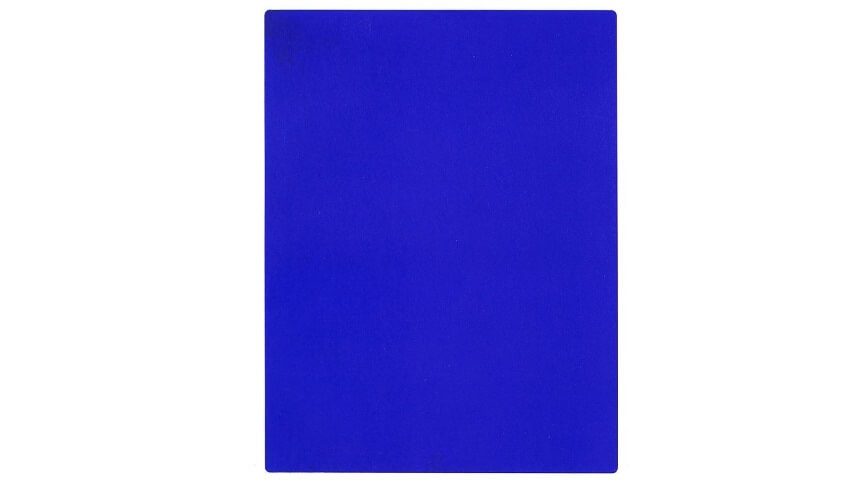

Yves Klein - IKB 191, dry pigment and synthetic resin on canvas laid on panel, 65.5 x 49 cm. (25.8 x 19.3 in.), © Yves Klein Archives

An Image of Absence

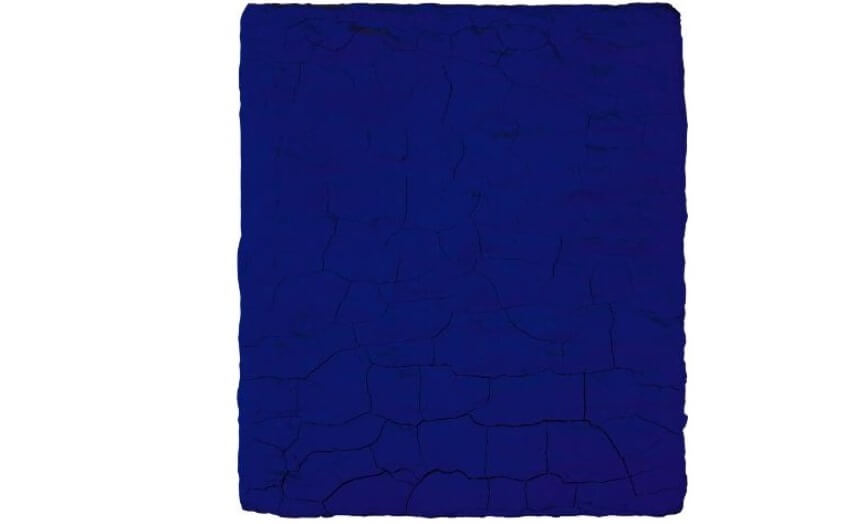

The first public exhibition of Klein’s art was a selection of his monochrome paintings, each one painted a different color. The show was well received, but viewers responded to the work as though it was meant to be purely decorative, which troubled Klein, whose intention was exactly the opposite. He had hoped viewers would appreciate what was absent in the works, not fetishize their materiality or their interrelationships. He reacted to the public’s misunderstanding by changing his approach. He worked with a paint manufacturer to develop a new, uniquely vibrant shade of blue paint, and for his next show he exhibited 11 monochromes painted this exact same color of blue .

The exhibition of blue monochromes traveled to four countries, bringing Klein international celebrity in Europe. The shade of blue he had created became known as International Klein Blue, or IKB, and his success brought him high profile opportunities. For example, he was commissioned to create several large-scale institutional murals, which he executed as giant IKB monochromes painted with sponges.

Fieroza Doorsen -Untitled (detail), 2014, Ink, pastel and acrylic on paper, 10.2 x 7.5 in

Fieroza Doorsen -Untitled (detail), 2014, Ink, pastel and acrylic on paper, 10.2 x 7.5 in

New Possibilities

Though many people unmistakably still fetishized his artworks, Klein continued to challenge the public perception of his, and of all, art. He worked in a multitude of mediums, exploring performance art; making sculptural forms of his friends’ bodies; covering models with paint and dragging them across surfaces, using their bodies as his paintbrush; all the while incorporating his iconic blue, IKB, as much as possible. Throughout his body of work he continued to expand on his primary investigation, an inquiry into what he called “the Void.”

The Void was both a concept to Klein, as well as the subtitle of his most famous exhibition. In that exhibition (full title: “The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility, The Void”), Klein removed everything from a gallery space except for an empty cabinet then painted every surface in the room white. He explained, “My paintings are now invisible and I would like to show them in a clear and positive manner.”

Fieroza Doorsen -Untitled (detail), 2010, Ink, tissue paper on paper, 10.4 x 7.5 in

Fieroza Doorsen -Untitled (detail), 2010, Ink, tissue paper on paper, 10.4 x 7.5 in

In The Zone

Klein’s empty gallery wasn’t about showing nothing. It was about showing the absence of something. It was about the idea that nothing and something are collaborative forces. In another work relating to the same concept, Klein sold off empty spaces in exchange for gold. He called the empty spaces Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility. They were places in which what was expected was missing, but what was present was the absence of it; places where new interpretations and new possibilities could manifest.

Klein’s work profoundly enlarged the public view about what could be considered art, while also challenging the accepted notions of what could be called representational. The legacy of his thoughts and work profoundly changed the art world, and influenced generations of artists to come. All he accomplished is particularly remarkable when considering that he made that huge impact in a relatively short amount of time. Klein’s first public exhibition was in 1955, and he passed away 7 years later in 1962, after suffering three heart attacks in three and a half weeks.

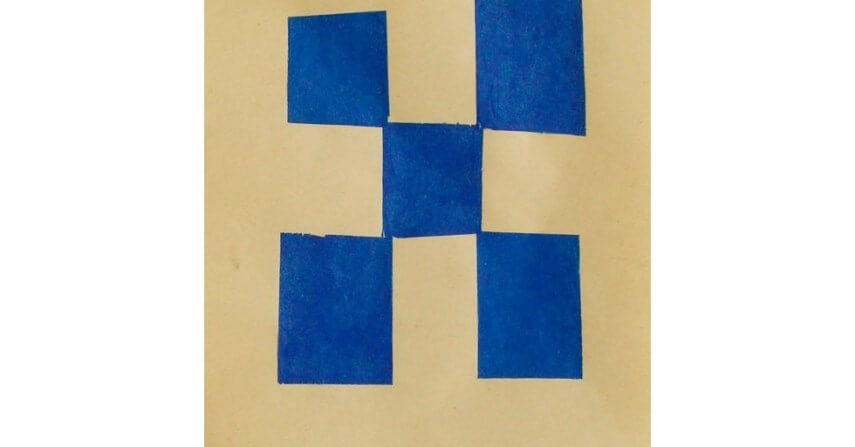

Yves Klein - Untitled Blue Monochrome, 1956, 27 x 31 cm, © Yves Klein Archives

Yves Klein - Untitled Blue Monochrome, 1956, 27 x 31 cm, © Yves Klein Archives

Representational Democracy

What was Klein’s exact influence? His efforts helped democratized realism. He defended one artist’s individual perception of reality as being as valid as that of any other. The “new realism” Klein helped usher in was really more of a total realism, a way of looking at all art as being representational, and of being inclusive of all ways of perceiving what reality could be.

Prior to this shift in perception, what defined abstract art was that it was somehow the result of a conscious departure from what could be called objective, or representational. Klein eliminated that delineation. Klein proposed that something that appeared to be abstract could perhaps more accurately depict reality than something that appeared to be representational. He demonstrated that in order to fully portray reality, nothingness is as vital as something-ness; emptiness is as important as fullness; and that the space between two objects is as much a part of reality as the objects themselves.

Featured Image: Yves Klein - Untitled Blue Monochrome (IKB 239), 1959, dry pigment and synthetic resin on canvas laid down on panel, 92 x 73.2 cm. (36.2 x 28.8 in.), © Yves Klein Archive

All images used for illustrative purposes only