Gutai Group - Gestural Abstract Movement from Asia

Written in 1956, the Gutai Art manifesto reads, in part, “We have decided to pursue enthusiastically the possibilities of pure creativity. We believe that by merging human qualities and material properties, we can concretely comprehend abstract space.” The avant-garde art collective known as the Gutai Group formed in Osaka, Japan, in 1954. Over the 18-year life span of the group, its artists radically transformed the global modern art scene with their ideas. Written by Yoshihara Jiro, the founder of group, their complete, 1270-word manifesto explains in detail their earnest philosophical intentions. It describes the art of the past as a fraud and an illusion, and insists that true art must contain the spirit of life. “Let’s bid farewell,” it states, “to the hoaxes piled up on the altars and in the palaces, the drawing rooms and the antique shops. Lock up these corpses in the graveyard.” Gutai called for a new art: a spirit-filled, living art that paid equal respect to the materials used in its realization and to the artist, without whose participation it could not manifest. Their efforts redefined Japanese artistic identity in the aftermath of World War II, and became a living demonstration of renewed Japanese interest in freedom, individuality and interconnectedness to the rest of the globe.

Man vs. Mud

Materiality was of primary concern to the first Gutai artists. They used materials in such a way that their essential physical qualities remained a visible and vital element of the work. They were inspired by the observation that decaying architectural ruins often seem alive, because time allows the raw materials used to create them to reassert their physical essence. That value is poetically expressed within the word gutai. Often translated as concrete, gutai could rather be translated as concretion, as in the process of becoming concrete. When, through the facilitation of an artist, matter transforms itself, while still embodying the true essence of its material properties; that is the spirit of gutai.

For a perfect demonstration of gutai consider Challenge To The Mud, performed in 1955 by Shiraga Kazuo. For this work, Shiraga hurled himself into a muddy swath of wet clay and proceeded to wrestle with it. Thrusting all of his body parts deep into the clay he made craters, mounds, trenches and shelves. He squeezed the clay into forms and carved patterns with his undulations. At the conclusion of the performance, the area in which Shiraga had wrestled with the mud was left as an artwork to be admired for its own qualities. The performance embodied the words of Yoshihara Jiro, who said, “In Gutai Art, the human spirit and matter shake hands with each other while keeping their distance.”

Shiraga Kazuo - BB64, 1962

Shiraga Kazuo - BB64, 1962

Light and Weight

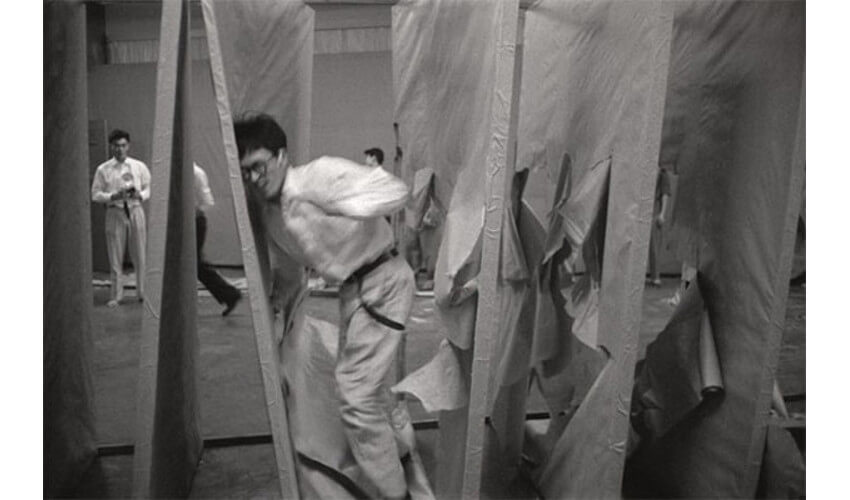

In 1956, Murakami Saburõ expanded on the art of Shiraga Kazuo, this time utilizing a synthetic material as his medium. For his performance called Laceration of Paper, Murakami framed multiple large sheets of paper and then arranged them in a tight line. Taking a running start, he jumped through the paper frames, bursting each one with a loud pop. After bursting through all of the paper sheets and coming out the other side, Murakami left behind a relic that demonstrated the potentially traumatic effects of human collaboration while also vibrantly expressing the essential physical qualities of paper.

That same year, Tanaka Atsuko took the use of synthetic materials to an even more extreme level through her creation of a piece called Electric Dress. This artwork consisted of a wearable suit made of painted light bulbs that lit up in a multi-colored display. The human artist within the suit literally animated the material, bringing it to life while also allowing it to express its true essence. The suit was also wired to periodically shock the wearer with a small jolt of electricity. The shock served to express the essence not of the synthetic material used for the work, the light bulbs, but of the natural material used in the work, electricity: a not so subtle expression of the danger inherent when humans interfere with the power of the natural world.

Murakami Saburo - Laceration of Paper, 1956

Murakami Saburo - Laceration of Paper, 1956

Pure Creativity

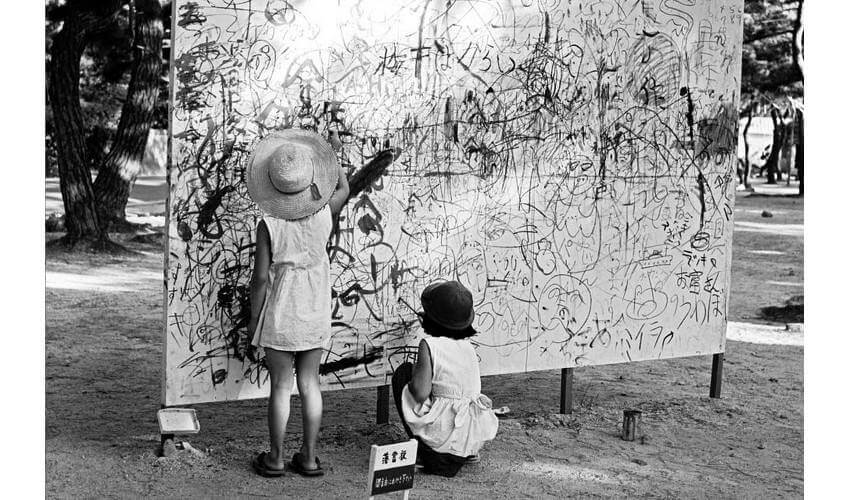

Aside from their respect for materiality, the next most important value held by the Gutai Group was their respect for creative freedom. Yoshihara Jiro succinctly expressed that concept in a work he made in 1956 called Please Draw Freely. The piece consisted of a massive blank surface set outside in the open along with an assortment of writing and drawing implements, along with an invitation to all people to come and express themselves in any manner they like. By allowing all people the chance for unlimited and unrestrained creative expression, Yoshihara transformed the concept of freedom into the medium, and turned the creative process into the work of art.

In their quest for freedom, the Gutai Group pursued every idea without restraint, in a spirit of sincerity. They painted with remote controlled cars and paint cannons, experimented with gestural abstraction, and tested a multitude of other approaches related to merging physicality with materiality. And in an effort to spread their encouragement to the rest of the world they also exuberantly corresponded by mail with other artists in several other countries, building an enormous community of likeminded souls. Their efforts forged connections with the artists who eventually went on to create the Fluxus movement, and they achieved breakthroughs in performance art, collaborative art, installation art, public art and many other popular contemporary modes of expression that were then just in their infancy.

Yoshihara Jiro - Please Draw Freely, 1956, Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition, Ashiya Park

Yoshihara Jiro - Please Draw Freely, 1956, Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition, Ashiya Park

Future Possibilities

Near the end of the Gutai Art manifesto Yoshihara Jiro mentions that some of their early work was being compared to the work of the Dadaists. To his way of thinking, that meant that the experiments of gutai artists were being misinterpreted as being absurd, or anti-art. Gutai artists stressed moving beyond the past, but acknowledged the vital importance of art in general, and the validity of some of their predecessors. Dada, on the other hand, was largely based on the premise of active disrespect for the past, and for all institutions, physical or otherwise, related to art. Dada was wildly creative, but also cynical, and often destructive. Gutai artists were simply asking what new possibilities could be imagined for the future.

In response to being compared to Dada, Yoshihara pointed out that while Dada deserves respect, the intentions of gutai are far different, because they are focused not on cynicism but on sincerity. In his manifesto he writes, “Gutai places an utmost premium on daring advance into the unknown world. Granted, our works have frequently been mistaken for Dadaist gestures. And we certainly acknowledge the achievements of Dada. But unlike Dadaism, Gutai Art is the product that has arisen from the pursuit of possibilities.” In 1972, Yoshihara Jiro passed away. Since he had been largely responsible for funding their activities, the Gutai Group subsequently disbanded. But before they ended their work, their spirit had touched artists all over the world and had inspired their, and future generations. Gutai lives on today in the respect artists have gained for multidisciplinary studio environments, in the work of experimental art collectives, and in every exhibition space that gives time and resources to artists pursuing previously unimagined ideas.

Featured image: Jiro Yoshihara - Circle, 1971

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio