Jean Dubuffet and the Return to the Essence

Sep 2, 2016

What is art? Where can we find it? How do we recognize it? What is the origin of the creative impulse? What is the purpose of making art? It was with questions such as these in mind that the French artist Jean Dubuffet traveled to the Sahara Desert in the late 1940s. Having just recently become re-dedicated to making art after a ten-year hiatus, Dubuffet hoped the trip would help him shake off the cultural influences he believed were inhibiting his artistic vision. He carried with him on the trip several journals and sketched the landscapes, creatures and scenes that he encountered. Under the theory that it would help him reconnect with his primal creative impulses, he imitated the style of the Arabic Saharan natives, whose art he considered pure and raw, and uninfluenced by cultural prejudices. At one point during this trip, he offered pencils and paper to an Arabic native he met in the desert and encouraged him to draw. The man imitated the style of the drawings Dubuffet had made in his journal. But it was a dual mimicry: a local imitating a foreigner’s imitation of the local style. Somewhere in this anecdote lurk profundities about how culture is created, about the reasons humans make art and about the ways style can be influenced. And somewhere in it the question is raised once again: what is art?

Jean Dubuffet and the Search For Art Brut

Having initially displayed remarkable talent as a young painter, Dubuffet walked away from art school after only six months, discouraged by its intellectual restrictions and institutional arrogance. He abandoned painting altogether, experimenting with a range of other interests and careers. But then all of a sudden in his 40s, Dubuffet reconnected with his creative instinct, having discovered renewed inspiration from what he would eventually call Art Brut. The translation of Art Brut is “raw art.” What Dubuffet had realized was that a whole world of creative phenomena existed outside of the formal art world, where untrained artists, including children and the insane were creating masterpieces of instinct and sincerity.

Dubuffet respected the lack of cultural baggage these untrained artist had. They were free. Their work had no connection to academic analysis or historical trends. They were not making art in order to be recognized, gain advantages, or participate in the market. They were making art for other reasons entirely, and engaging in a completely different process than that in which professional artists were engaged. He became inspired by their rawness and devoted himself to becoming unprofessional again; by unlearning what he had been taught, stating, “Amongst artists, as amongst card-players or lovers, professionals are a little like crooks.”

The Primal vs. the Cultural

He reverted to a childlike, primitive style of painting through which he attempted to connect with his most basic creative instincts. And he began collecting and exhibiting the works of untrained artists. To accompany one of his first exhibitions of Art Brut artists, he published a manifesto raging against academics and intellectuals and the false culture they had built up around art. In his manifesto, he stated, “Art hates to be recognized and greeted by its name; it runs away immediately. As soon as it’s unmasked, as soon as someone points the finger, it runs away. It leaves in its place a prize stooge wearing on its back a great placard marked ART, which everybody immediately showers with champagne, and which the lecturers lead from town to town with a ring through its nose.”

But this brought up an intriguing point. Does one have to be a child to make art like a child? Does one have to be wild in order to paint wildly? Or does each one of us have within us the ability to unlearn, to return to a state of childlike wildness? Dubuffet decided that the first priority if he was to learn how to master Art Brut was to rid himself entirely of ideas, which he saw as the product of culture, and the poison that was preventing him from making true art.

Jean Dubuffet - Mécanique Musique, 1966. 125 cm x 200 cm. ©Photo Laurent Sully-Jaulmes/Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris

The Wolf Howls

By the 1960s, Dubuffet had made a tremendous impact on the art world with his traveling Art Brut exhibitions, and with his childlike, primitive-looking paintings. Yet he continued to feel he was not in touch with his primal artistic impulse. Then one day in 1962, while making a doodle, he had a breakthrough. The doodle, a simple, thoughtless, unhindered drawing, somehow conveyed his artistic truth. He used it as the foundation for what would become his new style, an aesthetic he referred to as Hourloupe, from “hurler” meaning roar and “loup” meaning wolf.

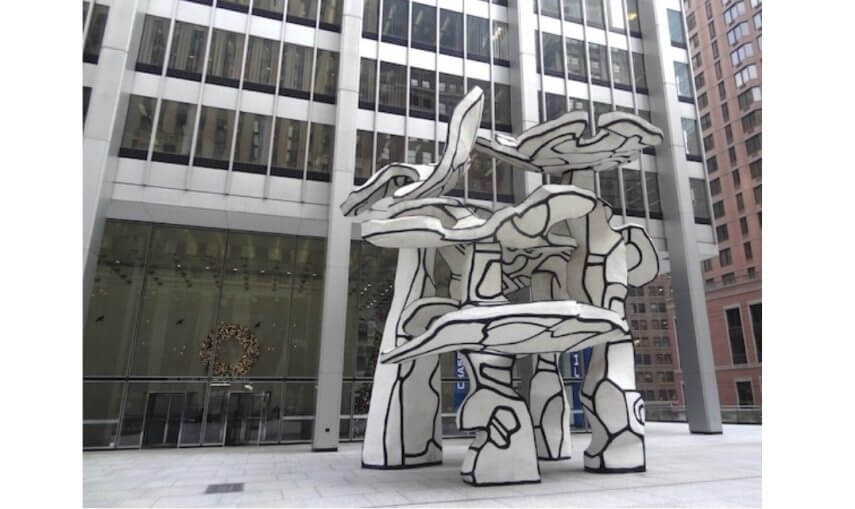

Dubuffet’s Hourloupe years were his most prolific yet. Not only did he create the iconic paintings that would define his idiosyncratic personal style, but he also crossed over into other aesthetic arenas. He made monumental public sculptures, which he celebrated for their ability to allow people to inhabit them, becoming part of the artistic experience. And he created what the Coucou Bazar, a stage production modeled after one of his paintings in which actors animated certain elements of the three-dimensional, bringing the artwork to life.

Jean Dubuffet - sculpture at Chase Manhattan Plaza, New York

A Savage Art

One of the most intriguing elements of Jean Dubuffet’s Art Brut is that it has nothing to do with aesthetics. In fact, Dubuffet believed that aesthetic qualities should be altogether ignored in favor of the emotive quality of a work of art. He advocated a total rejection of style in favor of the personal vision of the artist. As he wrote in his Art Brut manifesto, “the artists take everything (subjects, choice of materials, modes of transposition, rhythms, writing styles) from their own inner being, not from the canons of classical or fashionable art. We engage in an artistic enterprise that is completely pure, basic; totally guided in all its phases solely by the creator’s own impulses.”

In these words we find Dubuffet’s greatest legacy. In his attempt to describe and embody the spirit of Art Brut he answers those most basic and essential questions about art. He answers the question of what art is: art is vision. He answers the question of where we find art: we find it everywhere, not just in the approved venues and institutions. He answers the question of how to recognize art: we see it where it is least expected, not only where we predict it will be. He answers the question of the origin of the creative impulse: it emanates from a moment of lucidity. And he tells us what he believes the purpose of art to be: to transcend boundaries. By following his example, we can hope to return to the essence of art, which is unrelated to nationality, politics, economics, intellect and history, and which rejects false labels such as young or old, sane or insane, sick or well, trained or untrained. Art Brut teaches us that real art unites us in a common impulse shared by all.

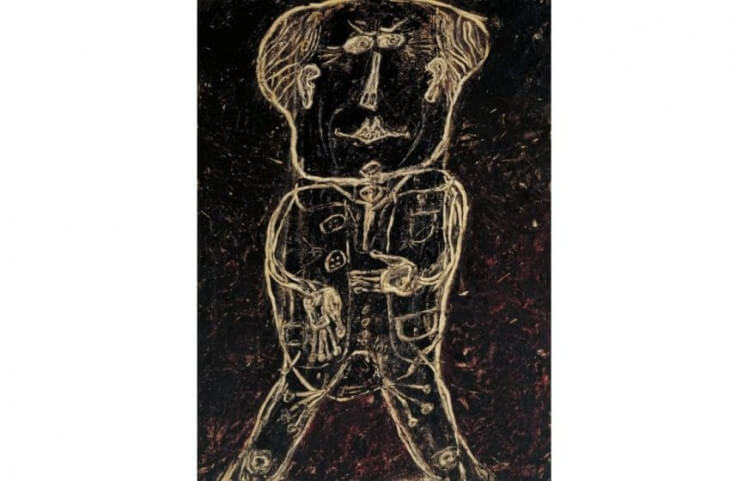

Featured Image: Jean Dubuffet - Monsieur Plume with Creases in his Trousers (Portrait of Henri Michaux), 1947. Oil paint and grit on canvas. Support: 1302 x 965 mm, frame: 1369 x 1035 x 72 mm. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio