Outsider Artists Whose Work is Seen as Abstract

Outsider art is an all-encompassing term that describes artists working outside of the formal art world. Outsider artists tend to be self-taught. Sometimes they work in folk traditions. Other times they are institutionalized, either because they have committed criminal acts or because they are confronting certain mental realities that make them severely vulnerable or possibly dangerous. Aside from its aesthetic rawness, what tends to be fascinating about outsider art is the ambiguous or unknown intent of the artists. Formally trained artists, whether they are in it for a career or just for a hobby, are almost always able, and sometimes even willing, to talk about their art, explain their intentions, and justify it to those who do not understand. But outsider artists seek no validation, and almost always offer no justification. They make art for their reasons, which normally have nothing to do with the rest of us. Do you remember the first time you made art? Why did you do it? Was it an instinct? Were you in search of something, like beauty? Or were you just playing? That earliest artistic impulse—the unmitigated, innocent spark of creativity that urges us to manifest something visual—that is what we so often see in outsider art. In celebration of the rich history of outsider art, today we highlight for you six abstract outsider artists. Their intentions may not be clear, and the meaning of their work may never be agreed upon. But in their aesthetic creations we see something intuitive and pure, and primary to the function of abstraction in art.

Anna Zemánková

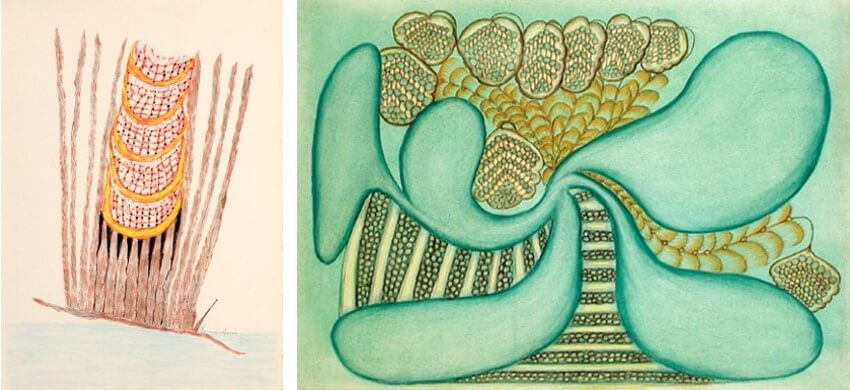

Tragedy, spirituality and the beauty of nature informed the work of Anna Zemánková. Born in 1908 in Moravia, part of modern day Czech Republic, she taught herself landscape painting in her 20s. But it was not until her 50s, after she sank into a deep depression following several moves and the death of one of her children, that she returned to art. While painting she believed she was connected to spiritual forces, and was channeling magnetic energy that could not be represented objectively. To express the forces with which she communed she painted abstract compositions loosely inspired by the patterns, shapes and colors she perceived in nature, particularly in flowers. Her paintings are what she is best known for, but in addition to paintings, she also made elaborate lampshades, poking holes in the shades to create abstract patterns with light.

Anna Zemánková - Untitled, 1980s, satin collage and combined techniques on paper (Left) and Untitled, pastel on paper, 1970s (Right)

Anna Zemánková - Untitled, 1980s, satin collage and combined techniques on paper (Left) and Untitled, pastel on paper, 1970s (Right)

Pascal Tassini

Belgian artist Pascal Tassini discovered his passion for making art late in life. Unable to fully care for himself due to a life long obsessive condition, he lived with his parents as an adult until they passed away. Then one of his brothers took over his care and introduced him to the Créahm Workshop, in Liège, Belgium. At first, Pascal was content cleaning and organizing the center, but he soon became inspired to make art. He painted and drew at first, but then began creating complex objects out of fabric. He often cocooned the various items he found or that were given to him as gifts. Using a technique of his own imagining, he even constructed for himself a studio tent in which he works. Visitors who wish to see him must allow him to first don a lab coat and take their pulse, healing them of their ills before they can enter his studio.

Pascal Tassini - Untitled fabric assemblages

Pascal Tassini - Untitled fabric assemblages

Pascal Tassini - Untitled fabric assemblages

Pascal Tassini - Untitled fabric assemblages

Eugene Andolsek

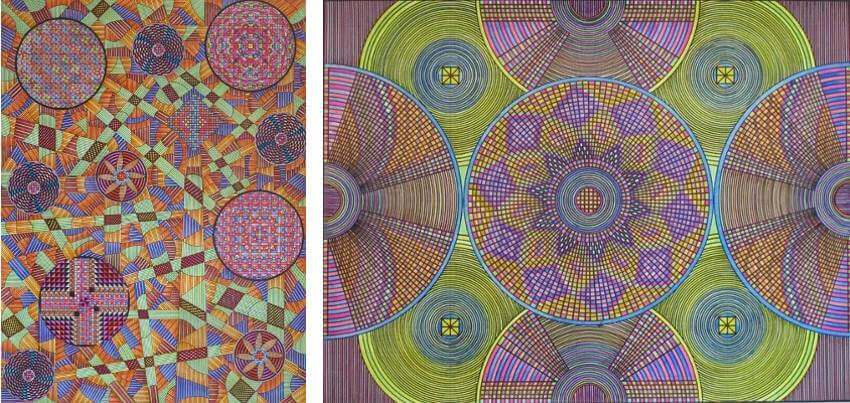

Like many outsiders, Eugene Andolsek never considered himself an artist. He drew with pens on graph paper for relaxation at his kitchen table as a respite from daily life. For decades he collected his spectacular geometric drawings in a trunk while working as a railroad stenographer and while caretaking for his ailing mother. After he retired and his mother passed away, he eventually lost his eyesight and had to check himself into a care facility. There, a worker discovered his artwork and recognized it as something special. In 2005, at age 84, three years before he died, Eugene saw his work exhibited for the first time, at the American Folk Art Museum. He was surprised by the positive attention his paintings received, having previously considered them at best to be useful perhaps as colorful placemats.

Eugene Andolsek - Two untitled geometric abstract ink drawings on graph paper

Eugene Andolsek - Two untitled geometric abstract ink drawings on graph paper

Judith Scott

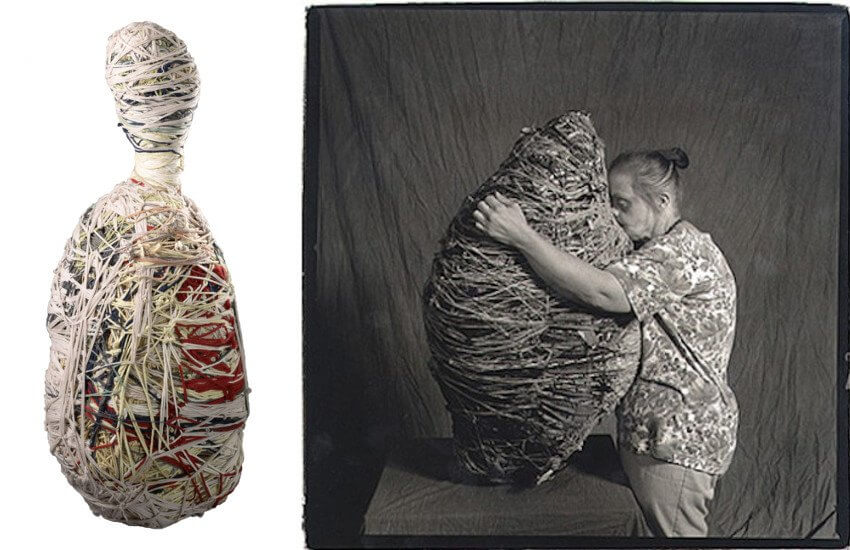

The abstract sculptural creations of Judith Scott offer a heart-achingly powerful expression of the humanity of this outsider artist. Born deaf, mute and with Down Syndrome, Judith spent nearly all of the first four decades of her life living under deplorable conditions in various institutions. Finally in 1986, at the age of 44, her twin sister took custody of Judith, and brought her home with her to Oakland, California. There, Judith was able to enroll in classes at the Creative Growth Art Center. That is where, for the first time, she began creating art. She collected various objects, winding them in elaborate networks of fibers until their form became obfuscated. The resultant sculptures sometimes do and sometimes do not reflect the form of the object with which she began. Though they resemble cocoons, it is more accurate to say they have undergone an opposite, though nonetheless transformative process. It is as though by being covered up their essential presence has been revealed.

Fiber-cocooned abstraction by Judith Scott (Left) and Judith Scott with one of her creations (Right)

Fiber-cocooned abstraction by Judith Scott (Left) and Judith Scott with one of her creations (Right)

Tetsuaki Hotta

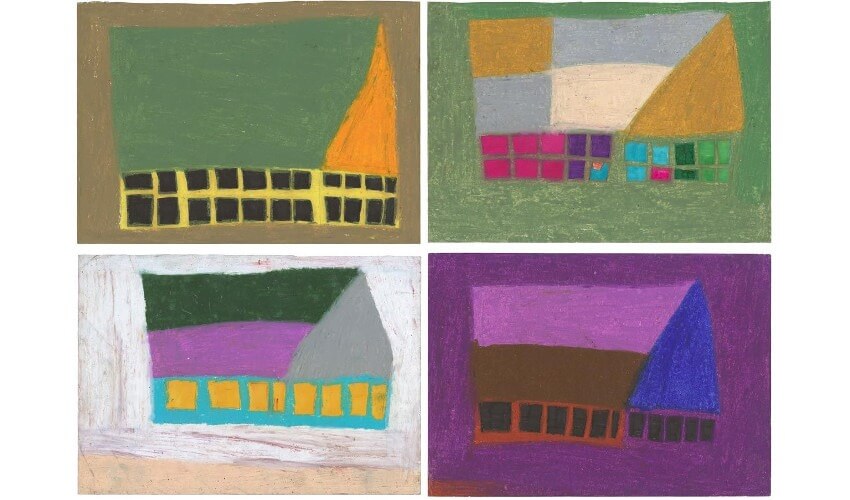

Japanese artist Tetsuaki Hotta was institutionalized at age 19 for what was described as a mental handicap. But when he began taking art classes at the institution where he lived it was quickly revealed that his capacity for advanced abstract thought was in tact. Since 1970, Hotta has exclusively been painting abstract geometric compositions resembling houses. He is completely disinterested in the forms that are present in his works. He uses the compositions purely as examinations of color and space on a flat plane. Seen together, these expressive, intuitive paintings are like the outsider art equivalent of the work of the German-American artist and teacher Josef Albers, who spent his life similarly examining color through his Homage to the Square series.

Tetsuaki Hotta - artwork

Tetsuaki Hotta - artwork

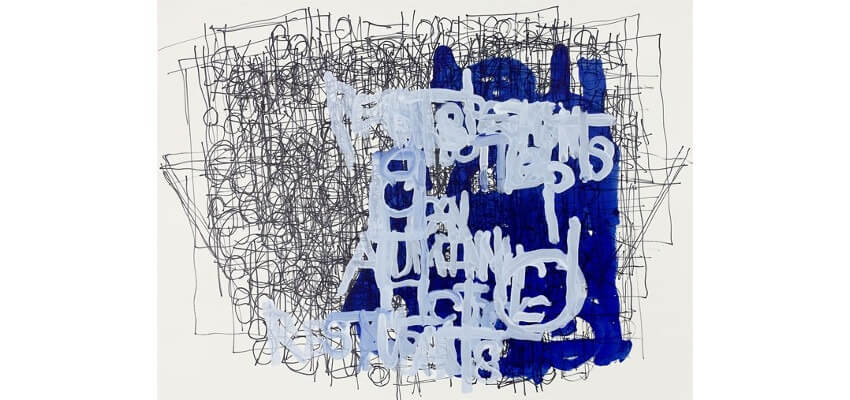

Dan Miller

California native Dan Miller was raised across the Bay from San Francisco in a town called Castro Valley. Born autistic, he, like Judith Scott, found his artistic calling at the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland. Dan Miller is preoccupied with text, using it not so much as an expressive entity in itself, but rather as an aesthetic medium through which compositional and aesthetic meaning might be produced. His compositions have evoked comparisons to the works of the abstract artist Cy Twombly, who also utilized glyphic forms and sparse color palettes in his paintings. Unlike Twombly however, Miller draws on actual text, culled from his inner world, then layers it continually until it reaches a point that is beyond readability. His work has been widely acclaimed, and is even included in the New York MoMA.

Dan Miller - Untitled, UD, acrylic, marker on paper, 57 x 76 in

Dan Miller - Untitled, UD, acrylic, marker on paper, 57 x 76 in

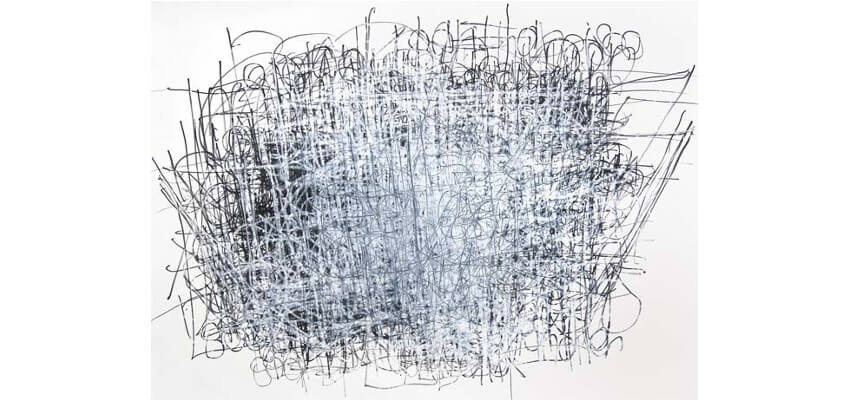

Dan Miller - Untitled (white over black), 2013, acrylic and ink on paper, 56 x 76 in

Dan Miller - Untitled (white over black), 2013, acrylic and ink on paper, 56 x 76 in

Essential Instincts

During the course of our research for this article, we came across the fascinating story of the British zoologist Desmond Morris. In addition to his work as a scientist, Morris was an outsider Surrealist artist. He showed his art in London in the late 1940s and early 50s. But his biggest contribution to art materialized when, in 1957, he exhibited the abstract paintings one of his colleagues from his day job: a chimpanzee named Congo. The idea of abstract art made by a chimpanzee may sound silly. It could even seem offensive. But some of the most famous artists in the world sought Desmond Morris out in order to acquire paintings by Congo. Salvador Dali and Pablo Picasso each owned one, and Joan Miro even traded one of his own works to Morris in exchange for a painting by Congo.

What Dali, Picasso and Miro comprehended was that humans share a primal, abstract aesthetic urge with other animals. The creative act is our universal heritage as denizens of this planet. Many different animals find pleasure in the exploration of pattern, shape, line, color, texture and composition. Dali even went to far as to say that the chimpanzee painted like a human, and that Jackson Pollock painted like an animal. Perhaps that speaks to why we take such pleasure in the work of self-taught artists and other people who make outsider art. They represent our hope that there is something pure, raw, primal, essential and universal about all of us, and that it can be expressed, and possibly understood, through art.

Featured image: Judith Scott - One of her fiber-cocooned abstractions

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio