Illusion and the Abstract in the Works of Jesus Rafael Soto

The difference between reality and illusion can sometimes be subjective. While a student at the School of Fine Arts and Applied Arts in Caracas, Venezuela, Jesús Rafael Soto tried studying Impressionism. But he could not understand it. The light in Impressionist paintings seemed unreal to him because the light in his tropical environment was so much harsher. To his eyes, Cubism seemed realistic because it broke the world up into planes, which was how he saw the landscape of his surroundings. “Later,” Soto once said, “when I arrived in Europe, I was able to understand Impressionism.” The lesson Soto learned from that experience is that the true nature of something cannot be understood without studying its relationship to something else. “Relationships are an entity,” he said, “they exist and so they can be represented.” Throughout his career, Soto explored the relationships of the physical world through his art. As a pioneer in kinetics he mastered how to convey movement in art, and demonstrated that the relationship between reality and illusion is dynamic, and that at times the two, in fact, become one.

Jesús Rafael Soto vs. the Past

Soto was born in 1923, in the colonial river town of Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela. His interest in art began early. He taught himself to copy famous paintings from books as a child. By age 16, he was supporting himself by hand-painting posters for the cinema in his town. And by 19 had earned a scholarship to study art in Caracas. His sincere passion drove him to study intensely in order to understand history and craft, and especially to comprehend what it was exactly that made something a work of art.

While in school, Soto was insulated by believers in Modernism. But after graduation, he took a position as the director of an art school in a small town. He quickly realized that whenever he tried to instill in his students some enthusiasm for the new, the other teachers, mired in the past, discouraged them, unraveling his influence. He realized the only way he could grow as an artist was to change his environment. Most of his friends from school had already left for Europe. “I was in such a state of despair,” he said later, “that one day I just locked up the school and abandoned everything. I left for Paris!”

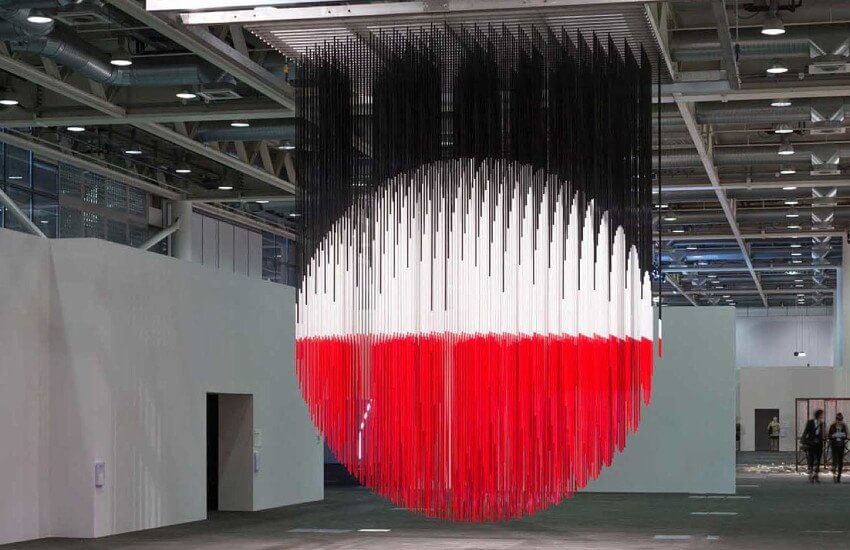

Jesús Rafael Soto - Sphère Lutétia, 1996. Perrotin. Installation. Paint on metal. 600.0 × 600.0 × 600.0 cm. 236.2 × 236.2 × 236.2 in. Basel 2015. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Jesús Rafael Soto - Sphère Lutétia, 1996. Perrotin. Installation. Paint on metal. 600.0 × 600.0 × 600.0 cm. 236.2 × 236.2 × 236.2 in. Basel 2015. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Moving Toward Something

Soto arrived in Europe in 1949, and was quickly absorbed into a small community of South American ex-pats with connections to the avant-garde artist community. Inspired by all of the experimentation going on, he started breaking down the idea of painting in his mind. He considered figuration and abstraction too wrapped up in the sympathies of the artist. He decided that if he wanted to take art somewhere new, he had to go back to a world of ideas that pre-dated the sophistication of modern art. He began focusing on relationships between fundamental visual elements.

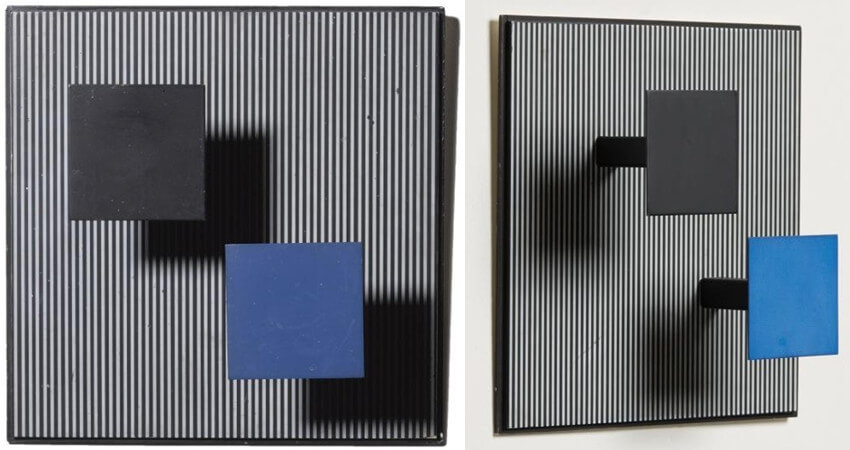

He made paintings focused on compositions of grids, dots, lines and squares, limiting his palette to eight basic colors. He analyzed how the simplified visual elements affected the viewer and how the eye interacted with the compositions. He noticed how he could use varying spatial relationships and differences in lightness and darkness to create a composition that would appear to change as the viewer moved around it. He could either trick the eye into perceiving movement where there was none, or create a composition that was impossible to perceive in its entirety from one viewpoint, thus requiring movement from the viewer.

Jesús Rafael Soto - Dos Cuadritos, side and front views. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Jesús Rafael Soto - Dos Cuadritos, side and front views. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

True Kinetics

But of course there were many artists working with movement and illusion in the Mid-20th Century. Soto wanted his art to express something fundamentally different. He was friends with various other artists who used machines to make their art move. And he also knew many practitioners of Op-Art, who were making artwork that tricked the eye into perceiving illusionary spatial phenomena. But he wanted to create movement without machines, and not through illusion alone, but through real world interactive relationships.

Jesús Rafael Soto - Example of Vibrations and Spirals. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Jesús Rafael Soto - Example of Vibrations and Spirals. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

To accomplish his goals he began experimenting with artworks called Vibrations, which feature patterned surfaces with other patterned elements suspended in front of them, creating ever-changing aesthetic experiences as viewers move around them. He also made pieces called Spirals, which feature a solid surface painted with a pattern and a second transparent surface suspended in front of it painted with a complementary pattern. The simple compositions in these pieces change before the eyes even when a viewer stands still, and when a viewer moves there is no end to the aesthetic variations that arise.

Jesús Rafael Soto - Example of Vibrations and Spirals. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Jesús Rafael Soto - Example of Vibrations and Spirals. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Penetrating Farther

While the aesthetic objects Soto was making were unique and beautiful, his philosophical achievements were not quite yet satisfactory to him. He had accomplished one of his goals, which was the physical integration of the viewer into his work, since his pieces required someone to be in the actual presence of them to receive the full effect. And he had achieved another vital goal, which was the integration of space and time into his art, since the full understanding of his pieces required a viewer to experience them from multiple perspectives over time while moving through space. But there was something else important he had yet to achieve, which was the communication of his core idea, what he called, “a universe filled with relationships.”

Soto accomplished this feat with a body of work he called Penetrables. Consisting of thin fibers hanging from the ceiling in a tight pattern, a Penetrable allows a viewer to enter it and to become completely absorbed into the volume of the work. Some Penetrables are simply clear or are painted a uniform color, while others contain painted elements that from afar present the illusion of a solid mass hanging in space, but then yield to the viewer upon contact, allowing an utterly different aesthetic experience from within.

Jesús Rafael Soto - the Penetrable in Caracas. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Jesús Rafael Soto - the Penetrable in Caracas. © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Integrated Forces

Soto called his Penetrables, “the revelation of sensible space.” Other kinetic artists relied on motors, pulleys or gadgets to create moving objects that were still only things to be watched. Even Soto made work that essentially only asked to be looked at by a viewer. With the invention of his Penetrables, people were no longer on the outside of the aesthetic phenomenon, looking in. “Today,” he said, “we know that man is not on one side and the world on the other. We are not observers but integral parts of a reality, which we know to be teeming with living forces, many of them invisible.”

This was the greatest achievement Soto attained. He evolved to consider people as potential collaborators with the artist in the aesthetic experience. The abstract notion that viewers are necessary in order to complete an artwork has been around for a long time. Soto took the idea to its ultimate extreme, proving that in fact there are no viewers, but only participants in an experience that without them would have no meaning, or possibly could not exist at all.

Featured image: Jesús Rafael Soto - the Houston Penetrable. 2004–2014. Lacquered aluminum structure, PVC tubes, and water-based silkscreen ink. Overall: 334 × 787 × 477 in. (848.4 × 1999 × 1211.6 cm). © Estate of Jesús Rafael Soto / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio