Grand Palais Welcomes a Grand Retrospective of Joan Miró Works

On 3 October, the Grand Palais in Paris will open Miró, an ambitious retrospective examining the oeuvre of Joan Miró. It has been 44 years since the museum has so honored this Modernist pioneer who called the French capital home for more than 20 years. The exhibition will feature more than 150 works. The selection will include paintings, drawings, sculptures, ceramics, and illustrated books. This is by necessity of course—Miró was a truly multi-disciplinary artist. He responded to the real world as an impetus for all of his creative works (no matter how abstract they seem to us as viewers). Because Miró was never certain ahead of time where his inspiration would come from, he stayed completely open to any medium, any material, and any technique that might appeal to him in the moment. His total openness had much to do with his love for accidents. He once said, “I provoke accidents—a form, a splotch of color. Any accident is good enough. I let the material decide.” Sometimes it was a speck of dust on a canvas that instigated a painting; other times it was a piece of driftwood that washed up on the beach that instigated a sculpture. If no accidents were evident at the time, he would force one, say, by crumpling up a piece of paper in order to be able to respond instinctively to the folds. Yet as this retrospective demonstrates, the work that grew out of these accidents was anything but accidental. Even if the initial inspiration came from an intuition, a dream, or a whim, the genius of Miró resides in the seriousness with which he took his responsibility to coax that random unconscious moment into a concrete work of art that could undeniably become part of the real world.

Evolution of an Artist

The gravity with which Miró painted is believed to have come from his training as a child. His initial education was as a business major. Born in Barcelona in 1893, he was raised in a family of craftspeople. His parents, perhaps motivated by their own financial difficulties, encouraged him to study commerce. He went along with their suggestion, and was excellent in school. But three years into his education he suffered a mental collapse. The anxiety of not studying art, of not following his true calling, left him unable to do anything at all. He dropped out of school, and two years later finally enrolled in art classes. He applied the same attention to detail, however, to his art studies as he had to business school. He carefully copied every figurative style his teachers taught him and then learned everything he could about the emerging Modernist styles, such as Symbolism, Cubism and Fauvism.

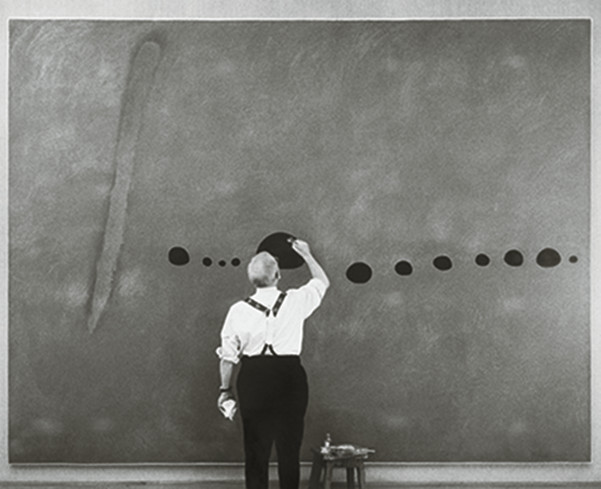

Anonyme. Joan Miró retouchant Bleu II, Galerie Maeght, Paris 1961. © Successió Miró / ADAGP, Paris 2018.

Photo Successió Miró Archive

It is there, at the point when Miró began learning about Modernism, that the retrospective at the Grand Palais begins. We see his “Self Portrait” from 1918, which demonstrates an embrace of the Fauvist sense of color. Next we see “Le Ferme,” painted in 1921, which shows Miró employing a Symbolist sensibility for the arrangements of objects in space. (This dreamlike vision of a rural scene is filled with haunting, dreamlike imagery and references to a multitude of abstract Modernist tropes like grids, geometric shapes, and fractured planes.) Next, the painting “Intérieur (La Fermière),” finished in 1923, demonstrates a radically simplified composition with a flattened picture plane, pared down forms, and exaggerated physical features on the figures. Finally, works like “Le Carnaval d’Arlequin” (1924) show Miró copying the visual style of the Surrealists. All of these early works are derivative of the work of the various famous artists who were working at the same time, but even if they are not completely original, they show the talent Miró had as a painter even at that young age.

Joan Miró - Autoportrait, 1919. Huile sur toile. 73 x 60 cm. France, Paris. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Donation héritiers Picasso 1973/1978.

© Successió Miró / ADAGP, Paris 2018. Photo Rmn-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau

Finding His Own Voice

The breakthrough for Miró came around 1926. Having lived in Paris for seven years, he had befriended many other artists and intellectuals, including the writer and art theorist André Breton who wrote the Surrealist Manifesto. Miró did not officially join the Surrealists, nor did he agree with everything they stood for, but he did come to understand from them the value of connecting to the world of his own dreams. The inner world of his imagination, the strange images from his dreams, and the visions he saw on the ceiling while dozing off at night—these things were solely his own, and they formed the basis for his strange, biomorphic, abstracted style. “Paysage (Le Lièvre)” (1927) shows a metamorphosing rabbit in a dreamlike landscape; “Painting (Snail, woman, flower, star)” (1934) blends the abstract with the figurative, and features text on the canvas spelling out exactly what the composition contains; “Painting (Birds and insects)” (1938) clarifies the childlike, yet oddly terrifying nature of his visual world; “Bleu II” (1961) boils his visual language down to the barest of essentials: all of these paintings demonstrate the unique personal style that we now associate with Miró.

As mentioned, in addition to bringing together each of the above mentioned paintings (along with dozens of other brilliant paintings from these periods), Miró at the Grand Palais also offers a deep dive into the three dimensional side of his practice. In many cases, the figures and forms in his sculptures and public works take on an even more uncanny presence than they do in his paintings. One example from this exhibition is “Jeune fille s’évadant” (Young girl escaping) (1967). Its hyper-sexualized female body has two faces—one tragic and one joyful—and is topped with a water spigot ready to burst: a disturbing vision of a thought-filled, confused, completely objectified creature. Like all of his work, this sculpture is undeniably part of the real world. Its abstract qualities invite us into a space of introspection and wonder, while its concreteness forces us to accept what is grotesque and surreal about everyday life. Miró at the Grand Palais is on view from 3 October 2018 through 4 February 2019.

Featured image: Joan Miró - Le Carnaval d’Arlequin, 1924-1925. Huile sur toile. 66 x 93 cm. États-Unis, Buffalo. Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery. Room of Contemporary Art Fund, 1940. © Successió Miró / Adagp, Paris 2018. Photo Albrigth-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo / Brenda Bieger and Tom Loonan

By Phillip Barcio