Juan Gris on the Verge of Abstraction

The two artists most commonly associated with Cubism are Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Rightfully so, since it was they who invented the style, and most passionately pursued its expressive possibilities. But it was Juan Gris, the so-called third Cubist, who is credited with explaining Cubism, a vital step that led to its acceptance into mainstream culture. Picasso and Braque were different from Gris in their attitudes and their approaches to their art. They were after something that had little to do with whatever style they were using. Gris, on the other hand, was methodical and analytical. He pursued Cubism precisely because of its stylistic qualities. For Picasso and Braque, Cubism was a matter of passion. For Juan Gris, it was a matter of taste.

The Illustrator Juan Gris

Juan Gris arrived in Paris in 1906, at the age of 19. Although he had studied painting in his hometown of Madrid, he was not necessarily intent on becoming a painter. He was a skilled illustrator, and both in Madrid and Paris he made a living submitting drawings and cartoons to various publications. The content of some of those cartoons, especially the ones he drew leading up to the onset of World War I, have been used to suggest that Gris was an anarchist or a left-wing radical. But his personal letters suggest instead that he was a stoic intellectual who wanted to be left completely out of politics. That he was mistaken in his passions is testament to his talent as an illustrator of the ideas of others.

That exact talent served Gris well on his journey to Cubism. Soon after moving to Paris, Juan Gris moved into the same building as Picasso. He visited his countryman frequently and witnessed firsthand many of the artistic advancements Picasso made. Unlike Gris, Picasso was proudly anti-war and commonly included political statements in his work. Although that passion perhaps evaded Gris, the formal aspects of what Picasso was doing made a tremendous impact. Around 1910, inspired by its aesthetic qualities, Gris began painting Cubist images of his own. His ability to take in a lot of information, analyze it quickly and then explain it served him well in this effort, as it allowed him to focus on and enhance the specific abstract aesthetic elements that made Cubism unique.

Drawing Hard Lines

One of the most important aesthetic traits Juan Gris focused on was the use of hard, solid lines. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were both endeavoring to capture a sense of something. They wanted to portray a heightened realistic impression of a visual experience in which a viewer sees something from multiple different simultaneous viewpoints. They wanted their images to capture the movement and multiplicity inherent to how people truly experience reality. To that end, not only did they divide their images up into different planes to represent different viewpoints, but they also merged those planes, fading the lines and blending the colors in order to add to the sense of dynamism.

Juan Gris abandoned that search for dynamism, instead using hard lines and well-defined shapes. He focused purely on the idea of showing different viewpoints, embracing that aesthetic element for its own abstract qualities. Rather than suggesting movement, Gris painted static compositions divided up into sections; he analyzed each section from a new viewpoint and painted it in a precise, two-dimensional way. This aesthetic choice highlighted one of the purely formal elements of Cubism, and it also completely flattened the architecture of the picture plane. It is the most distinct difference between his work and that of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

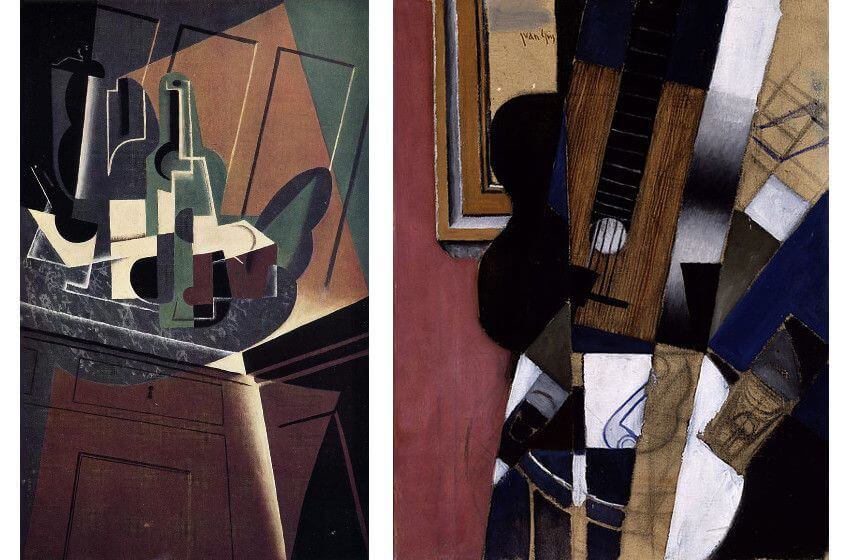

Juan Gris - Still Life with Checked Tablecloth, 1915. Oil and graphite on canvas. 45 7/8 x 35 1/8 in. (116.5 x 89.2 cm). Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, Purchase, Leonard A. Lauder Gift, 2014. The Met Museum Collection. (Left) / Juan Gris - Guitar and Glasses, 1914. Pasted papers, gouache, and crayon on canvas. 36 1/8 x 25 1/2" (91.5 x 64.6 cm). Nelson A. Rockefeller Bequest. 956.1979. MoMA Collection © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (Right)

Juan Gris - Still Life with Checked Tablecloth, 1915. Oil and graphite on canvas. 45 7/8 x 35 1/8 in. (116.5 x 89.2 cm). Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, Purchase, Leonard A. Lauder Gift, 2014. The Met Museum Collection. (Left) / Juan Gris - Guitar and Glasses, 1914. Pasted papers, gouache, and crayon on canvas. 36 1/8 x 25 1/2" (91.5 x 64.6 cm). Nelson A. Rockefeller Bequest. 956.1979. MoMA Collection © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (Right)

Paintings About Cubism

In addition to his use of hard lines, Juan Gris also dealt differently with the issue of light than did Picasso and Braque. In their paintings, they addressed light as they perceived it from each of the various viewpoints they captured, a choice that often resulted in the presentation of an unintelligible multitude of light sources spread across an equal number of different planes. Gris maintained one light source uniformly illuminating multiple points of view. That change gave his paintings a more clearly defined, illustrative quality that highlighted the idea that the image was intentionally abstracted, purely for aesthetic purposes.

Juan Gris also used a bright, vivid color palette that was much different than that of Picasso and Braque, making his compositions more lucid and easily understandable for the general public. In a lecture he delivered in 1924, he stated that all of these formal choices were intentional for the way that they were demonstrative of the theories of Cubism. He wanted the focus to be on style. He said he was not attempting to convey a sense of reality. Rather, the focus should be on craft. In other words, while Picasso and Braque made Cubist paintings, Gris was making paintings about Cubism.

Juan Gris - The Sideboard, 1917. Oil on plywood. 45 7/8 x 28 3/4" (116.2 x 73.1 cm). Nelson A. Rockefeller Bequest. 957.1979. MoMA Collection © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (Left) / Juan Gris - Guitar and Pipe, 1913. Oil and charcoal on canvas. 64.7 x 50.1 cm. 25.5 x 19.7 in. Dallas Museum of Art (Right)

Juan Gris - The Sideboard, 1917. Oil on plywood. 45 7/8 x 28 3/4" (116.2 x 73.1 cm). Nelson A. Rockefeller Bequest. 957.1979. MoMA Collection © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (Left) / Juan Gris - Guitar and Pipe, 1913. Oil and charcoal on canvas. 64.7 x 50.1 cm. 25.5 x 19.7 in. Dallas Museum of Art (Right)

Absoluteness vs. Relativity

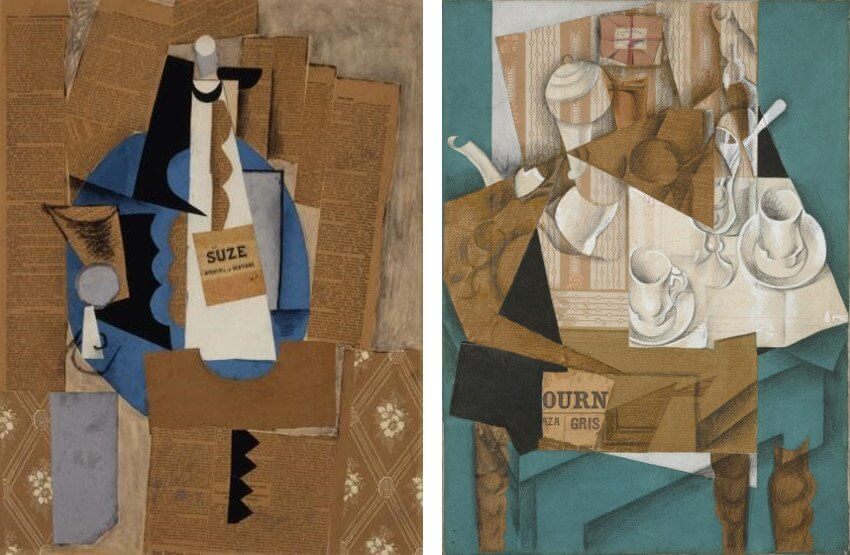

Another major element of Cubism was that it was the first Modernist art movement to incorporate elements of collage. Both Picasso and Gris incorporated collage elements into their work, and in particular they both commonly used newspaper clippings in their compositions. Again, this was one of the key ways that Picasso used a Cubist technique to express something larger in a painting, but Gris used a Cubist technique to illustrate the abstract concepts of Cubism itself. For example, juxtapose the 1912 Picasso collage, La Bouteille de Suze, with the 1914 Gris collage, Breakfast.

Both contain collage newspaper elements. In the Picasso collage, the newspaper clippings contain actual news of war. In the Juan Gris collage, the newspaper clipping features an altered headline stating his name. Picasso was making a political statement with his work, as the news of war interjected itself into the experience of everyday life at the café; the very real threat of violence is, so to say, right there on the surface. Gris was making a different statement. The scene is not at a café; it is in a home, a private world. The news is not of society, it is of himself.

Pablo Picasso - La Bouteille de Suze, 1912. Pasted papers, gouache, and charcoal. 25 3/4 x 19 3/4 in. University purchase, Kende Sale Fund, 1946. WU 3773. Kemper Art Museum © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (Left) / Juan Gris - Breakfast (Le Petit déjeuner), 1914. Gouache, oil, and crayon on cut-and-pasted printed paper on canvas with oil and crayon. 31 7/8 x 23 1/2" (80.9 x 59.7 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). 248.1948. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (Right)

Pablo Picasso - La Bouteille de Suze, 1912. Pasted papers, gouache, and charcoal. 25 3/4 x 19 3/4 in. University purchase, Kende Sale Fund, 1946. WU 3773. Kemper Art Museum © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (Left) / Juan Gris - Breakfast (Le Petit déjeuner), 1914. Gouache, oil, and crayon on cut-and-pasted printed paper on canvas with oil and crayon. 31 7/8 x 23 1/2" (80.9 x 59.7 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). 248.1948. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (Right)

Reinventing Cubism

The Spanish sculptor Manuel Martinez Hugué once said, “The one who explained Cubism was poor Gris.” The author Gertrude Stein, who was an avid collector of works by both Juan Gris and Picasso, used to say that Gris was the only artist that could annoy Picasso. Perhaps the reason Picasso was so annoyed by him was because Gris was so eager to explain what Picasso saw as inexplicable, or irrelevant.

Ironically, by the early 1920s, Picasso embraced the formal explanation Juan Gris made of Cubism, agreeing that all along it had been about abstract things like line, form and color. But perhaps that apparent flip-flop should not be seen as a reversal of opinion at all. Perhaps instead that statement could be interpreted as a demonstration of what both Picasso and Gris would likely agree is the most important abstract aspect of Cubism: that there are many different ways of looking at everything.

Featured image: Juan Gris - Still Life with a Guitar, 1913. Oil on canvas. 26 x 39 1/2 in. (66 x 100.3 cm). Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, 1998. 1999.363.28. The Met Museum Collection

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio