The Story Behind Wassily Kandinsky's Composition VII

“Composition VII” (1913) by Wassily Kandinsky is considered by many abstract art aficionados to be the most important painting of the 20th Century—perhaps even the most important abstract painting ever created. Yet frequently when someone looks at it for the first time they react negatively, expressing anger, frustration, or even disgust. Undeniably, it is a difficult painting, especially for those who are new to abstract art. First of all, it is massive, measuring 200 x 300 centimeters. Secondly, the surface is entirely covered with countless overlapping amorphous forms, seemingly random lines, and a minefield of colors, some vivid and some blurred. Nothing references the known natural world. Only the illusion of depth is perceptible, but the space into which it recedes bears no semblance to reality. The painting could easily look like nonsense to anyone unwilling to work towards unravelling its mysteries. But for those willing to study it with an open mind, “Composition VII” can pay enough intellectual, visual, and even spiritual dividends to last a lifetime. And I am not being hyperbolic. This painting truly is that important to some people—not only because of its visual, physical, or formal qualities either, but because for Kandinsky and those who appreciate him, “Composition VII” has come to be understood as a concrete embodiment of spiritual purity in art.

Stairway to Seven

Between the years 1910 and 1939, Kandinsky painted 10 canvases to which he assigned the title “Composition.” Today, only seven of those paintings survive, the first three having been destroyed during World War I. But photographs of the first three Compositions do exist. Although they lack color information, we can ascertain from them some clues about the essence of the visual journey Kandinsky was on as he created each one. That journey initially involved transforming traditional landscapes and figures into simplified, biomorphic masses, and then coaxing those masses into shapes and forms that became more and more abstract. In “Composition III,” for example, the forms of humans and animals are still recognizable, milling about, perhaps playing or perhaps fighting, or both, in a sort of pastoral environment. But then in “Composition IV” (1911), the forms are almost unrecognizable. We are told by Kandinsky that in this image there are figures reclining in the lower right, and two towers standing atop a hill in the upper right, a scene he describes as simultaneous war and peace. But it would be difficult for me to arrive at this conclusion without his explanation.

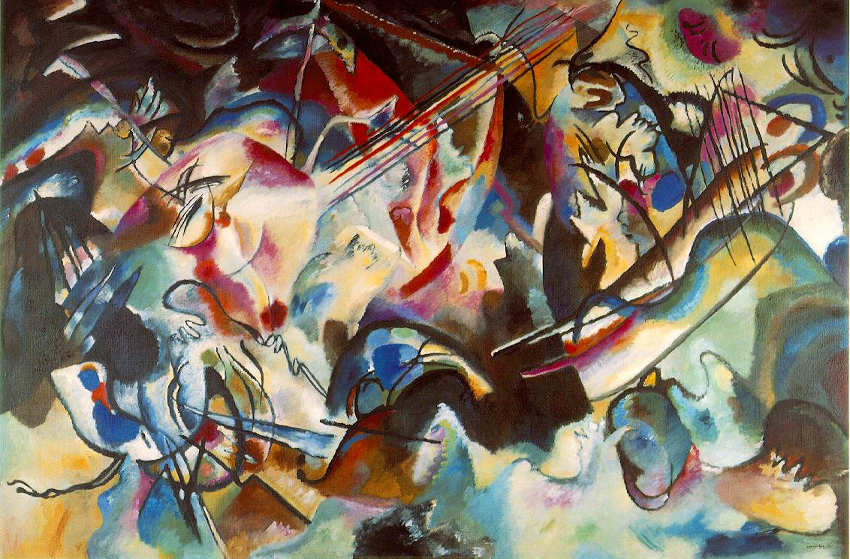

Wassily Kandinski - Composition VI, 1913. Oil on canvas. 195 x 300 cm. State Hermitage Museum

“Composition V” (1911) is even more abstract, and yet the emotion it expresses also feels more intense than in the earlier Compositions. In this painting, the forms in the painting still somewhat relate to the natural world since slightly humanoid figures and quasi-natural features, however pared down, are interspersed throughout the image. Almost totally abstract, however, is “Composition VI,” which Kandinsky painted two years after “Composition V.” Its most prominent feature is its lines, such as the six parallel lines in the middle of the image that resemble the neck of a guitar. What this painting represents, according to Kandinsky, is “the Flood,” meaning the biblical story of Noah. He attempted to distill the emotional, psychological, and spiritual essences of the story—destruction and creation; fear and hope—into a visual exploration of balance and harmony. About “Composition VI” he wrote, “the original motive of the painting (the Flood) was dissolved and transferred to the internal, purely pictorial, independent and objective existence.” Nonetheless, the painting still clearly includes some figurative elements, which tie its visual language to the external world.

An Expression of Inner Feeling

“Composition VII” is considered to be so important because it is the first time Kandinsky felt that he achieved the ideal for which his Composition series was named. In the last paragraphs of the last chapter of his seminal book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which Kandinsky published in 1910, he describes three different types of artistic inspiration. The first, which he calls “impression,” he describes as a direct, artistic impression of outward nature. The second, which he calls “improvisation,” he describes as “unconscious, spontaneous expression,” similar to the later Surrealist practice of automatic drawing. The third, which he calls “composition,” he describes as “an expression of a slowly formed inner feeling, which comes to utterance only after long maturing.” When it comes to “Composition VII,” the phrase “long maturing” is key. When he painted “Composition VII,” Kandinsky was living in Munich. Based on the historical record he kept at the time, we know that he planned “Composition VII” for months, creating more than 30 preliminary sketches for it in various mediums. Each preliminary sketch builds towards an image that is completely devoid of both “impression” and “improvisation.”

Wassily Kandinski - Composition VII, 1913. Oil on canvas. 79 x 119 in (200.6 x 302.2 cm). Tretyakov Gallery

Shortly after finishing this milestone, Kandinsky was forced by the outbreak of World War I to return home to Russia. Depressed about the war he barely painted at all for years. It was 10 years before he resumed his Composition series. “Composition VIII” (1923) translates the abstract imagery of its predecessor into a purely geometric visual language. “Composition IX,” which was not completed until 1936, is not purely abstract, but reintroduces the idea of “impression” by adding floral forms and other natural imagery. “Composition X” (1939), which was completed five years before Kandinsky died, is highly symbolic, and also shockingly modern looking, even now. However, though each of these later Compositions, and each of the six that preceded it, could be considered visionary, what makes “Composition VII” stand apart is the fact that by achieving thoughtful, methodical, mature, and total abstraction, it fulfills the ultimate ideal that Kandinsky was trying to achieve, not only with this series but with all of his 20th Century works. It is the first time Kandinsky achieved with painting what he believed musicians achieved with music: a pure translation of feelings into formal abstract elements that are capable of expressing the human spirit.

Featured image: Wassily Kandinski - Composition V, 1911. Oil on canvas. 74.8 x 108.2 in (190 x 275 cm). Private collection.

All images via Wikimedia Commons.

By Phillip Barcio