Space-Filling Sculptures and Unusual Materials - The Art of Karla Black

Nov 29, 2017

In Moby Dick, Herman Melville wrote, “There is no quality in this world that is not what it is merely by contrast. Nothing exists in itself.” It seems comparing things is just what humans do. It is how we understand our place in the universe. But as Karla Black reminds us in her latest solo exhibition at Modern Art in London (on view through 16 December), the urge to understand reality through comparison can be a scourge that can prevent us from experiencing something new. Black insists her work does exist in itself. Rather than comparing or contrasting her sculptures with previously known things, or worse, assigning them meaning, Black prefers we simply experience them. Her work “exists as a physical reality in the world,” she says. “Rather than saying, ‘What is the meaning of this sculpture’, I would prefer to ask, ‘What are the consequences of this sculpture.’”

Resisting Definition

Karla Black is a philosopher as well as an artist. After earning her BA in Fine Art at the Glasgow School of Art in her native Scotland, she stayed to earn a Masters in Philosophy and then a second Masters in Fine Art. It is no surprise then that Black tends to look at every aspect of her studio practice from an idiosyncratic, open minded perspective. One of the things people often say about her work is that is defies easy description, because it does not fit the traditional definitions of sculpture, painting or installation. To Black, that is a moot point. She looks back to art school, when her instructor claimed sculpture has to be self-supporting—something that stands or sits on another surface of its own accord. Black instinctively rejected that description as something untested and inherently limiting.

She calls all of her works sculptures, whether they hang from the ceiling, hang on a wall, sit on the floor or occupy every aspect of a given space. She calls them sculptures because each is an independent entity—a self-referential object—even though it may defy traditional expectations or contain a multitude of seemingly divisible parts. Rather than getting bogged down in irrelevant aesthetic labels, Black feels it is more important to free herself to make new things. That is a gift to herself. It allows her to liberate her imagination. It is also a gift to viewers, since it liberates us from having to pretend we know more about these objects than we do. It lets us experience them with the same freshness of mind with which they were created.

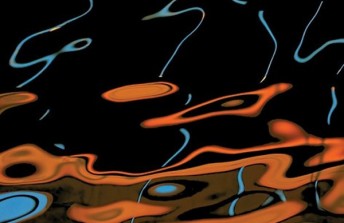

Karla Black - installation view, Modern Art, London, 2017, courtesy Modern Art, London

Karla Black - installation view, Modern Art, London, 2017, courtesy Modern Art, London

Rearranging the World

Black prefers to keep the materials she uses raw. She employs whatever the physical world is made up of and for the most part endeavors to leave it in its original state, just rearranging it, recombining it into new, autonomous objects. The list of elements she has used in her work includes natural substances like chalk, synthetic construction materials like plaster, thread, paint and tape, and commercial products like cosmetic creams and gels, cellophane, towels, toilet paper and plastic bags. But in an odd way, the fact that she leaves these elements in their raw state makes the work extra challenging. Because the work is constructed from recognizable products and materials from every day life, viewers cannot help but be engaged with the sensorial presence of the work.

Each material has a smell that brings up memories. Some, like that of packing tape, might be mundane; others, like that of a particular type of soap, might come laced with emotion. Each material also has a texture. Though we may not feel entitled to, we find ourselves drawn to touch the work. And of course because of their material makeup, her works possess an optical presence that is instantly recognizable to our eyes. She brings materials together to form something novel, which lets us know we are in the presence of the unknown. But the uncanny onslaught of sensory input we receive from the work makes it nearly impossible not to contextualize it, or to seek refuge in the harbor of allegory and meaning.

Karla Black - installation view, Modern Art, London, 2017, courtesy Modern Art, London

Karla Black - installation view, Modern Art, London, 2017, courtesy Modern Art, London

Recapturing Human Nature

Even if Black cannot control how we react to the work, she can control how she feels when creating it. To that end, she has avoided learning many traditional art techniques, such as stretching a canvas by hand. She says, “I don’t want to have those technical skills because I feel like that closes off any possibility of my own individual experience of finding my way through to some sort of solution that might be a bit more surprising.” She wants to feel free, in an animal sense. The fruits of civilization, such as inherited standards and practices, frequently stop usfrom connecting with our primal roots. Black wants to have a direct, physical experience while making the work, and for us to have a similar experience when interacting with the objects she makes.

There is a limit, however, to how much freedom Black allows with her work. Even if she has created an intuitive, site-specific piece, once the work is complete its attributes are set in stone. She rigorously documents every aspect of each finished piece then when it sells or is shown elsewhere, she requires it to be recreated exactly according to its original characteristics. She even obligates buyers to provide her with ongoing evidence their purchase is being precisely maintained—a demand that will extend to her estate when she dies. This might seem like a contradiction: she wants her work to be perceived as free but also rigid; unique but also precisely duplicable. Such a quandary might give a philosopher fits. But if we can overcome our human training that tells us we have to understand and explain everything, even contradictions might melt away. That is just one of the ways the work of Karla Black may help us recapture something essential about our nature.

Karla Black - installation view, Modern Art, London, 2017, courtesy Modern Art, London

Karla Black - installation view, Modern Art, London, 2017, courtesy Modern Art, London

Featured image: Karla Black - installation view, Modern Art, London, 2017, courtesy Modern Art, London

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio