Why Laura Owens’ Approach to Painting Is so Innovative

Nov 15, 2017

More than once I have heard an artist say that Laura Owens saved painting. It is an odd statement. It implies painting was in danger of being destroyed at some point, presumably in the past four decades or so since that is how long Laura Owens has been alive—and that it therefore needed a savior. Such academic theories as the ones that say painting is dead or painting is dying or painting has never lived are unprovable, and thus, at times, can be both comical and agonizing to listen to. But they do have a point. They are intended to convey the attitude that art must remain relevant. To say painting is need of saving just means that painting is in danger of becoming irrelevant. And so to say that Laura Owens saved painting just means that she somehow made that danger subside, at least temporarily. But a question worth asking is: To what is painting supposed to be relevant? Society? Maybe. But more importantly, painting must always remain relevant to painters. Every new painter who is thinking of picking up a brush—that is who must be convinced of the meaning and potential of what they are about to do. When people say Laura Owens saved painting, that is what they mostly mean. They mean this artist, by her example, is a testament to why it matters that people keep picking up brushes, keep stretching canvases, and keep making their marks. That is why she is cited by painters of all ages as an inspiration. It is also why in 2003, just nine years out of graduate school, she became the youngest artist to be given a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles since that museum opened in 1979. And it is why she was chosen this year to be the subject of the first mid-career retrospective of any artist at the new location of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Do Not Be Afraid of Anything

In conjunction with its current Laura Owens retrospective (on view through 4 February 2018), the Whitney published a monumental book detailing every aspect of the contribution Owens has so far made to art. It is quite literally one of the biggest art books ever. It consists of more than 600 pages of historical and academic writing about her life and art, and features hundreds of photographs of her work. But there is one entry within it that stands out as essential to me, not just for understanding Laura Owens the person or Laura Owens the painter, but also for understanding those who regard her as a personal hero. That entry is a copy of a list Owens wrote in her journal when she was in her 20s titled, “How to be the Best Artist in the World.”

The list, which is gaining fast traction on social media thanks to a mention in a recent New Yorker profile of Owens written by Peter Schjeldahl, includes advice as simple as “Think big,” and “Say very little,” and as complicated as, “Know that if you didn’t choose to be an artist, you would have certainly entertained world domination or mass murder or sainthood.” But the most important item on that list in my opinion is, “Do not be afraid of anything.” That one directive has defined all of the work Owens has made so far, and has also defined the criticism she has withstood, the mistakes from which she has learned, and the battles from which she has refused to walk away. It is the hallmark of her success, and the reason people say she saved painting.

Laura Owens - Untitled, 1997. Oil, acrylic, and airbrushed oil on canvas, 96 × 120 in. (243.8 × 304.8 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; promised gift of Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner P.2011.274, © the artist

Laura Owens - Untitled, 1997. Oil, acrylic, and airbrushed oil on canvas, 96 × 120 in. (243.8 × 304.8 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; promised gift of Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner P.2011.274, © the artist

What There Is To Fear

The first fearsome thing that could easily have scared Owens away from her career as a painter was the inherent bias of what should really be called the Art Academia Industrial Complex. As a student at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), she faced the sexism of a painting professor who encouraged only the male painters in class to work abstractly. As a student in the Masters program at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), she was faced with a critical mass of teachers and fellow students who preached that painting was passé, and that only “Post Conceptualism” could possibly address the complex ways formalism, art history and social issues were converging on the shores of contemporary life.

Owens ignored all of those biases, if not always fearlessly at least despite her fear—and that is the true definition of courage. She formed a club with other female abstract artists at RISD. And she defied her teachers and fellow students at CalArts and embraced painting as her primary aesthetic concern. She made paintings that expressed the one thing that has truly never been expressed before in painting: Laura Owens. When you look at the array of works included in the current Whitney retrospective, you see what appears to be a fantastical range of styles and subjects. All of it is different but all of it is the same, because all of it is personal. Like Walt Whitman said of himself, Laura Owens contains multitudes. We all do. Owens saved painting because she reminds us of that. She reminds us that the way to be unafraid in front of a canvas is simply to free yourself to paint what is uniquely your own. Express yourself. That is what she does. And understanding her work really is just that simple.

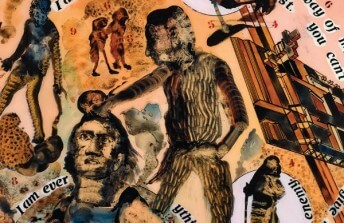

Laura Owens - Untitled, 2000. Acrylic, oil, and graphite on canvas, 72 x 66 1/2 in. (182.9 x 168.9 cm). Collezione Giuseppe Iannaccone, Milan (Left) and Untitled, 2006. Acrylic and oil on linen, 56 x 40 in. (142.2 x 101.6 cm). Charlotte Feng Ford Collection (Right), © the artist

Laura Owens - Untitled, 2000. Acrylic, oil, and graphite on canvas, 72 x 66 1/2 in. (182.9 x 168.9 cm). Collezione Giuseppe Iannaccone, Milan (Left) and Untitled, 2006. Acrylic and oil on linen, 56 x 40 in. (142.2 x 101.6 cm). Charlotte Feng Ford Collection (Right), © the artist

356 Mission

It is especially fitting that this, the first major retrospective Laura Owens exhibition in 14 years, is being mounted by the Whitney Museum of American Art. There is something uniquely American about Owens, beyond the fact of her citizenship. Partly it has to do with her work, which is brave and free—two solid, landmark characteristics that are imbedded into the psyche of all American souls, whether they were born in, or live in America or not. But the most ardently American thing that currently defines Owens is what she has been doing besides painting lately in her bookstore/gallery/public gathering space at 356 South Mission Road in Los Angeles.

In 2012, Owens was searching around Los Angeles, the city that had been her home for decades by then, for a space suitably large to exhibit a new body of work—a series of paintings so gigantic they would be constructed on site, since they would be preposterously difficult to transport. She found an empty warehouse in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of LA, which was perfect. With help from two partners, she rented the space and in 2013 mounted her planned exhibition. I had the pleasure of attending that show, and walked away from it feeling that I had just seen the most powerful painting exhibition of my life. The gallery was cavernous, industrial, and yet was dwarfed by the presence of the work. In front of the space was a bookstore, and out back food was being served, music was playing, and people were talking and laughing.

Laura Owens - Untitled (detail), 2012. Acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, charcoal, yarn, and cord on hand-dyed linen, 33 panels, 35 1/2 x 33 1/4 in. (90.2 x 84.5 cm) each. Collection of Maja Hoffmann/LUMA Foundation (Left) and Untitled (detail), 2012. Acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, charcoal, yarn, and cord on hand-dyed linen, 33 panels, 35 1/2 x 33 1/4 in. (90.2 x 84.5 cm) each. Collection of Maja Hoffmann/LUMA Foundation (Right), © the artist

Laura Owens - Untitled (detail), 2012. Acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, charcoal, yarn, and cord on hand-dyed linen, 33 panels, 35 1/2 x 33 1/4 in. (90.2 x 84.5 cm) each. Collection of Maja Hoffmann/LUMA Foundation (Left) and Untitled (detail), 2012. Acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, charcoal, yarn, and cord on hand-dyed linen, 33 panels, 35 1/2 x 33 1/4 in. (90.2 x 84.5 cm) each. Collection of Maja Hoffmann/LUMA Foundation (Right), © the artist

The American Way

After that inaugural exhibition, Owens decided to continue renting the space. She mounted exhibitions of other artists, hosted classes and lectures, and put on film screenings. And why not? The space was vacant. This is America. Why should someone not be able to rent any space they want? But her presence in the neighborhood has since set off a firestorm amongst some neighborhood residents. Owens is seen as an unwelcome occupier, and a harbinger of gentrification. Protesters representing Boyle Heights anti-gentrification efforts converged on the Whitney Museum to demonstrate against the Owens retrospective. They also routinely protest outside of her space in Boyle Heights.

Owens has met with representatives of the protest groups in an effort to reach understanding, but they have demanded she leave, and will accept nothing less. They also want her to publicly state she was wrong to come there and that she has learned her lesson. But Owens is not leaving. Not yet. She is brave. She has a right to be there. This intimidation by anti-gentrification protestors is no different than the actions history has shown us of those who intimidate people of color, or religious minorities, or refugees, trying to force them not to open businesses or buy homes in “their neighborhoods.” America has a long history of this kind of nonsense. But it also has a long tradition of diversity, and resistance to the powers of divisiveness. If you have a chance to see her current Whitney retrospective, please do, not only to discover why Laura Owens saved painting. But also to show your support for someone who exemplifies bravery, inventiveness, originality, and individuality—four characteristics that define what it means to be an artist, an American, and a free human being.

Featured image: Laura Owens - Untitled, 1997. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 78 x 84 in. (198.1 x 213.4 cm). Collection of Mima and César Reyes. © the artist

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio