The Most Important Collection of Latin American Abstract Art Opens at MoMA

The Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros (CPPC) has become recognized as the largest and most influential collection of Latin American abstract art in the world. In 2016, its founder Patricia Phelps de Cisneros gave MoMA 102 artworks from the collection dating from the 1940s to the 1990s. The gift included works by such luminaries as Lygia Clark, Gego, Hélio Oiticica and Jesús Rafael Soto, and recently formed the basis of the exhibition Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction, a major survey of Latin American Modern and Contemporary art that opened at MoMA in October 2019. In addition to providing a sweeping overview of 20th Century developments in South American abstraction, the CPPC also offers insights into the cultural exchanges that occurred between South American, European, American and Russian artists in the aftermath of World War II. That exchange is particularly evident in a suite of photos of the campus of Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas (CUC) included in the Sur moderno exhibition. One of the most stunning examples of a total artwork anywhere in the world, the CUC was constructed between 1944 and 1967 and designed by Venezuelan architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva. The visionary campus intersperses artworks by European, Russian and American artists such as Alexander Calder, Hans Arp, Victor Vasarely and Fernand Léger with the works of Latin American artists and designers such as Francisco Narváez, Armando Barrios, Mateo Manaure, Pascual Navarro, Oswaldo Vigas and Alejandro Otero. Despite its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the CUC has lately fallen into disrepair—a casualty of economic and social divisions across Latin America that can be traced to the same Post War cultural connections that helped inspire the artistic heritage celebrated in Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction. Its inclusion in this exhibition is a potent reminder of how critical it is for contemporary audiences to acknowledge the deep ties that bind Latin America with the rest of the world.

The Art of Power

Patricia Phelps de Cisneros began collecting art while traveling through Latin America in the 1970s. After realizing how shockingly little of the enormous South American artistic legacy was represented in major world museum collections, she transformed her personal collection into the CPPC. In the decades since, the CPPC has loaned and donated hundreds of works to major institutions in Europe, the US, and South America. It has also published more than 50 books, catalogues and monographs geared toward expanding global understanding of Latin American art. The collection is organized into five categories—Modern Art, Contemporary Art, Colonial Art, the Orinoco collection (representing the work of indigenous artists from the Amazonas region), and Traveler Artists to Latin America (works by European and American artists who travelled to the region from the 17th through the 19th century). The most substantial aspect of the collection is Geometric Abstract art from the Post World War II period.

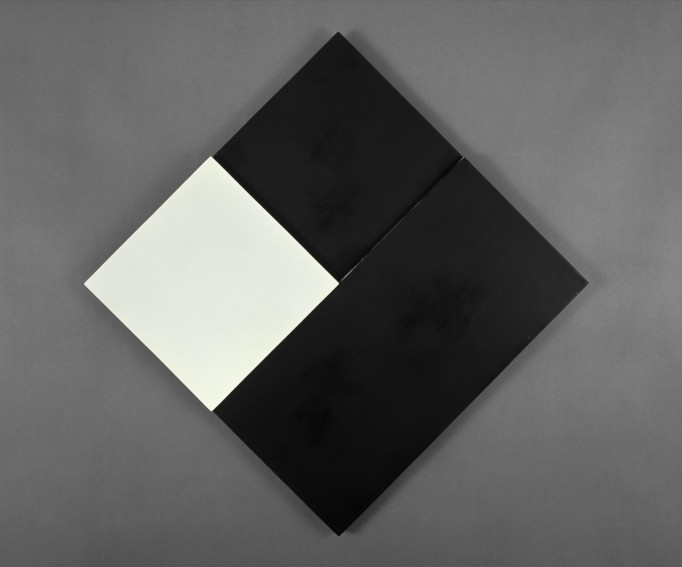

Lygia Clark - Contra relevo no. 1 (Counter Relief no. 1), 1958. Synthetic polymer paint on wood. 55 1/2 × 55 1/2 × 1 5/16″ (141 × 141 × 3.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Promised gift of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund. Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

World War II was extraordinarily impactful for Latin American culture. Though every Latin American country was independent by 1898, deep economic and political ties between them and their former European colonizers lingered throughout the early 20th century. After the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor later that same year, almost every Latin American nation joined the Allies in declaring war on the Axis Powers. This strained or ended some existing trading relationships, so the United States stepped in, providing economic relief by trading weapons and cash for land leases for military bases. One purpose of this deal was to help fend off possible invasions by German and Italian forces coming from Africa, but some South American nations benefitted more than others, causing suspicions and past rivalries to flare. Meanwhile, sympathies among artists and intellectuals in Latin America were split between the various political philosophies of their allies, which included Communism, Democratic Socialism and American Free Market Capitalism.

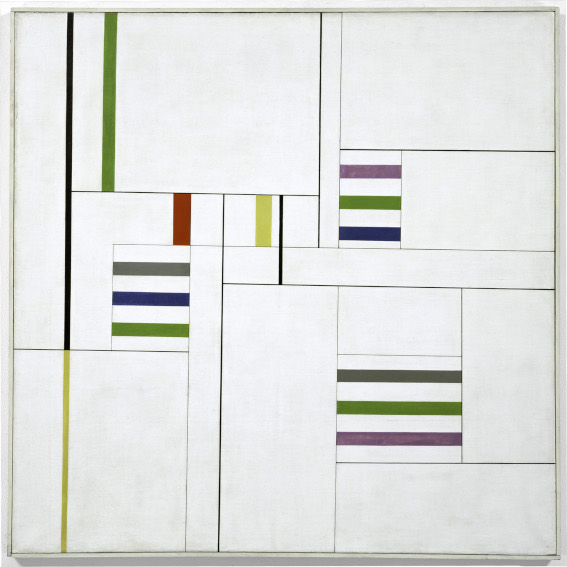

Alfredo Hlito - Ritmos cromáticos III (Chromatic Rhythms III), 1949. Oil on canvas. 39 3/8 × 39 3/8″ (100 × 100 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund

The Power of Art

All of these political and social complexities are evident in the work of Latin American avant-garde artists that were active in the decades following World War II. Artists like Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Hélio Oiticica transformed the cold calculations of European Concrete Art into the Neo Concrete movement, which used a similar visual language but embraced a more sensual approach to the plastic arts. Jesús Rafael Soto similarly built upon the works of artists like Piet Mondrian by taking them into the third dimension and adding elements of time and movement, even encouraging viewers to touch and interact with the work. These advancements, he believed, were essential to make abstract art approachable to everyday people who could finally then feel they were not alienated from the aesthetic world.

Installation view of Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction―The Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2019 – March 14, 2020. © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Heidi Bohnenkamp

Grand architectural projects such as the CUC in Venezuela, or the planned city of Brasilia—a Modernist architectural utopia that became the capital of Brazil in 1960—were an organic outgrowth of the democratization Post War Latin American artists brought to abstract art. Their perspective, which was expressed by the Brazilian poet Ferreira Gullar in such essays as the Neo Concrete Manifesto and Theory of the Non-Object, took for granted that aesthetics are not an outgrowth of pure science and theory, but are an essential part of the human experience—with all of the sensuality, emotion and openness that implies. To an even greater extent than the Bauhaus visionaries, their legacy demonstrates how to create a society filled with practical total artworks that welcome everyone and relate to everyday life. Yet, as Patricia Phelps de Cisneros has pointed out, it is shocking how little the rest of the world knows about the rich legacy of these Latin American abstractionists. Perhaps their politics frightens us. In any case, Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction is one step towards correcting our vision. Yet, even this exhibition, and in fact the whole CPPC, only tells a small part of the story of Latin American abstract art. Hopefully there are more corrections to come.

Featured image: María Freire - Untitled, 1954. Oil on canvas. 36 1/4 × 48 1/16″ (92 × 122 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund in honor of Gabriel Pérez‑Barreiro. © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio