Behind the Light and Space Movement at MCA Chicago

Jan 19, 2018

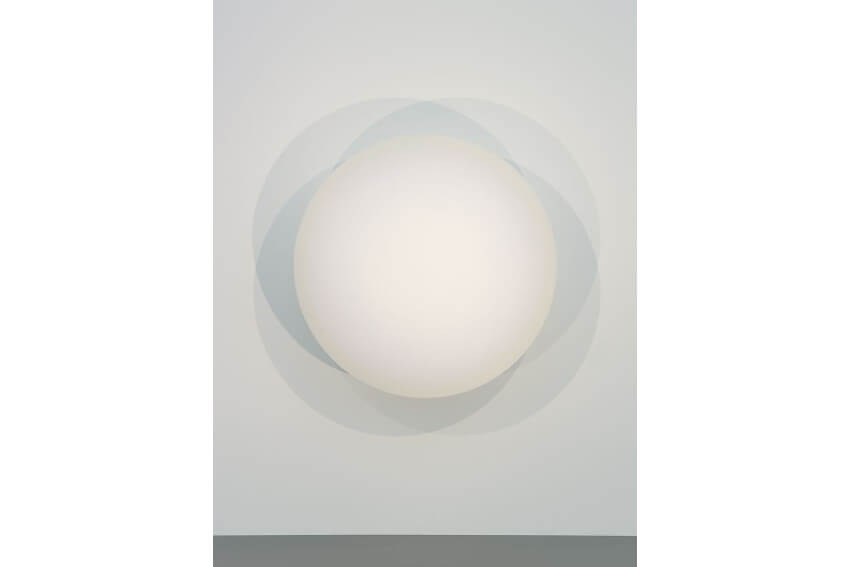

I credit the Light and Space Movement with first opening my mind to abstract art. In my youth, I was irritated by anything I could not understand. Abstract art only added to my confusion, and increased my angst. That all changed when I encountered an untitled artwork by Robert Irwin at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, my local museum at the time. The work was one of the so-called “discs” Irwin made in the late 1960s—it was already more than 25 years old when I saw it. It consisted of a convex, acrylic circle jutting out from the wall, cross-lit by four lights that cast four identical, circular shadows. Its presence transformed me. I felt more like I was in a sacred space than I had any of the hundreds of times I had previously stood in a church or a temple. It was not the work that felt sacred, or even the environment—it was that my mind suddenly opened up to the beauty of what it did not already know. In the blink of an eye, not understanding became a delight; confusion became wonder. As I walked through the rest of the museum, I saw every other abstract work in a new context. I even saw myself differently. This year, a new exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago will offer a chance for everyone to experience what I experienced way back when—the allure and enchantment of the Light and Space Movement. Titled Endless Summer, the exhibition brings together works from the MCA permanent collection with recent gifts from the estates of Walter and Dawn Netsch. Taking its name from the 1966 film in which surfers travel the world following perfect weather and endless waves, the exhibition is an attempt to illuminate the ideals that first inspired the Southern California artists for whose work the Light and Space Movement received its name.

The Power of the Void

Right off the bat I should say that Endless Summer (the MCA exhibit, not the film) has a glaring weakness—the lack of work by John McLaughlin. Though almost no writers credit him as such, McLaughlin was the philosophical and visual source on which all other Light and Space art is based. He was the first Southern California artist to explore the conceptual and visual language that later inspired so-called first generation Light and Space artists like Irwin, James Turrell, Helen Pashgian and Larry Bell, as well as second generation Light and Space artists like Lita Albuquerque and Mary Corse. Some dismiss McLaughlin because he was self-taught. Others ignore him because his work does not fit neatly into the “finish fetish” monicker that often accompanies academic discussions of the Light and Space Movement. But no earnest discussion of the history and values of Light and Space art can be complete without him.

Peter Alexander - Brown Black Wedge, 1969. Cast polyester resin; 91 ¾ × 4 × 3 15/16 in. (233.1 × 10.2 × 10 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of the Estates of Walter Netsch and Dawn Clark Netsch, 2014.54. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Peter Alexander - Brown Black Wedge, 1969. Cast polyester resin; 91 ¾ × 4 × 3 15/16 in. (233.1 × 10.2 × 10 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of the Estates of Walter Netsch and Dawn Clark Netsch, 2014.54. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

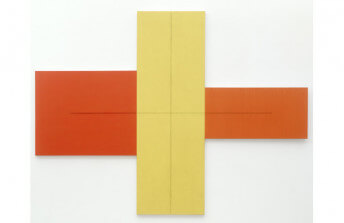

McLaughlin took his artistic inspiration from three sources: Zen philosophy, which taught him that the void between objects is as important as objects themselves; the writings of Kazimir Malevich, which taught him the universality of geometric shapes; and the work of Piet Mondrian, which convinced him that total abstraction was essential to a progressive aesthetic practice. Working in Dana Point, a small surfing town between Los Angeles and San Diego, in the late 1940s, McLaughlin fused those ideas, creating purely abstract paintings that used the space between geometric shapes to, as he put it, “intensify the viewer's natural desire for contemplation.” By painting colored rectangles onto neutral backgrounds, he employed the complementary forces of darkness and light—emptiness and fullness—to inspire viewers to question their perception. He used what is supposedly present to draw attention to what is supposedly missing. He revealed the power of the void—the foundation on which the work of Light and Space art is built.

John McCracken - Untitled, 1967. Fiberglass, polyester resin, and wood; 96 3/16 × 10 1/8 × 3 1/8 in. (244.2 × 56.4 × 7.9 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Ileana Sonnabend, 1984.53. © The estate of John McCracken courtesy David Zwirner, New York. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

John McCracken - Untitled, 1967. Fiberglass, polyester resin, and wood; 96 3/16 × 10 1/8 × 3 1/8 in. (244.2 × 56.4 × 7.9 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Ileana Sonnabend, 1984.53. © The estate of John McCracken courtesy David Zwirner, New York. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

What Is Present

When you walk into a James Turrell Skyspace, you see an environment that is concrete. And yet, within it, a space is left open—a void. The sky shows through the void. Lights illuminate the interior environment. But what is the heart of the work? Is it the light? Is it the environment? Is it the void? The perception of the work shifts with time. You begin to question the perceptual reality, and contemplate whatever else your mind starts to consider. Similarly, when you stand in the presence of a Helen Pashgian installation, your eye is first drawn to the luminous towers. But soon you become aware of the space around them, where shadows and light interplay. You perceive the least corporeal elements of the work—the light and space—as the most important. You wonder what the true subject of the work is. Your understanding of what is important evolves. This is the magic of Light and Space art.

Robert Irwin - Untitled, 1965–67. Acrylic lacquer on shaped aluminum; 60 in. dia. × 4 in. (152.4 dia. × 10.2 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Lannan Foundation, 1997.40. © 2017 Robert Irwin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

Robert Irwin - Untitled, 1965–67. Acrylic lacquer on shaped aluminum; 60 in. dia. × 4 in. (152.4 dia. × 10.2 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Lannan Foundation, 1997.40. © 2017 Robert Irwin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

Because of the movement on which it reflects, which was so important to the development of abstract art as we know it today, I recommend visiting Endless Summer while it is at the MCA Chicago (27 January – 5 August 2018). Just note that the exhibition is incomplete. It is heavily weighted toward male artists; it does not examine the full roots of the Movement; and it leaves many influencers out of the story. But the MCA is not claiming to be putting on a Light and Space Survey. This is intended to be a small glimpse into a much larger world. Use it as a starting point to discover off-the-beaten-path permanent works, like the Dwan Light Sanctuary in New Mexico; the Turrell Skyspace on the campus of Rice University in Houston; the Dan Flavin installation at Chiesa Rossa in Milan. Use it to begin your own adventure into a movement designed to expand your perception. Use it to open your mind to the power and potential of abstract art.

Featured image: Ed Ruscha - News, 1970. Screen print on paper; portfolio of six, each sheet: 23 × 31 ¾ in. (58.4 × 80.6 cm), each framed: 29 × 37 1/8 in. (73.7 × 94.3 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Nicolo Pignatelli, 1979.29.3. © Ed Ruscha. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

All imegs used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio