When Miriam Schapiro Used Computers to Generate Geometric Abstract Art

Jan 17, 2018

Miriam Schapiro was a legendary figure in the art world for more than half a century. She was a masterful visual artist, an influential teacher, and a brilliant theorist. But her most commonly known legacy relates to her importance to the first wave Feminist Art Movement. Schapiro was one of the founders of the Pattern and Decoration Movement (1975 – 1985), which confidently challenged typical Modernist adoration of male, western aesthetic tendencies. She co-founded the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California, along with Judy Chicago (who is said to have coined the phrase “feminist art”). And she was one of the artists involved in Womanhouse (1972), a groundbreaking installation that transformed a dilapidated, 17-room mansion in West Hollywood into perhaps the most visionary site-specific group exhibition of all time—one which was visited by more than 10,000 people in its one month existence and is the subject of two documentary films. But in addition to the massive influence Schapiro had in reshaping our understanding of the relationships between identity, culture, art, power and history, she also underwent several fascinating formal aesthetic evolutions as an artist—and that is one part of her legacy that has not adequately been told. An exhibition running through 17 February 2018 at Honor Fraser in Los Angeles takes a small step toward correcting that oversight, by featuring eight paintings that Schapiro created during one specific moment in her career—a period between 1967 and 1971, when she became a pioneer in the then nascent field of computer-aided art.

Formal and Conceptual Changes

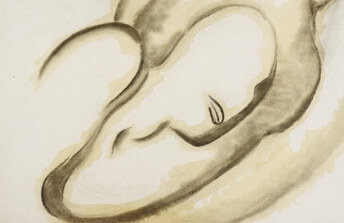

Schapiro at various times experimented with more than half a dozen mediums, including painting, drawing, textiles and sculpture. At any point during that evolution, she easily could have stopped searching and simply stuck with whatever style she had developed at that moment, and still created an epic, definitive oeuvre. But she constantly pushed herself into uncharted territory, both formally and conceptually. In the 1950s, she made a name for herself in the competitive and crowded New York art world with her hypnotic, mystical looking, lyrical abstract paintings. Their complexity and depth reveals her mastery of color and technique. But she abandoned that style in search of something more personal. She experimented with collage and lithography, and in the early 1960s arrived at a body of work she called the Shrine series—quasi-Surrealist, geometric compositions reminiscent of vertical altarpieces, containing figurative references to femininity and art history. These haunting and strange works do not fit in with anything her contemporaries were doing. They reveal an artist willing to experiment and unafraid to stand apart.

Miriam Schapiro - Installation view, Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, 2017

Miriam Schapiro - Installation view, Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, 2017

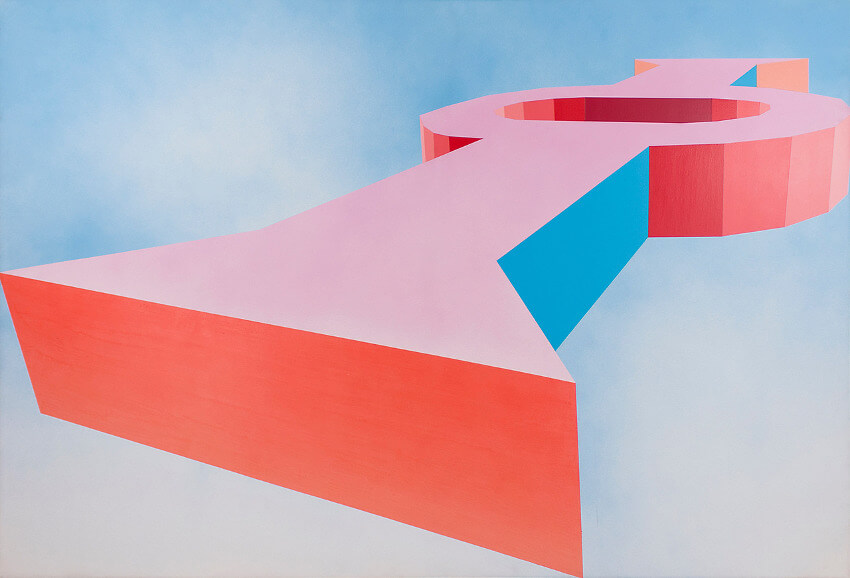

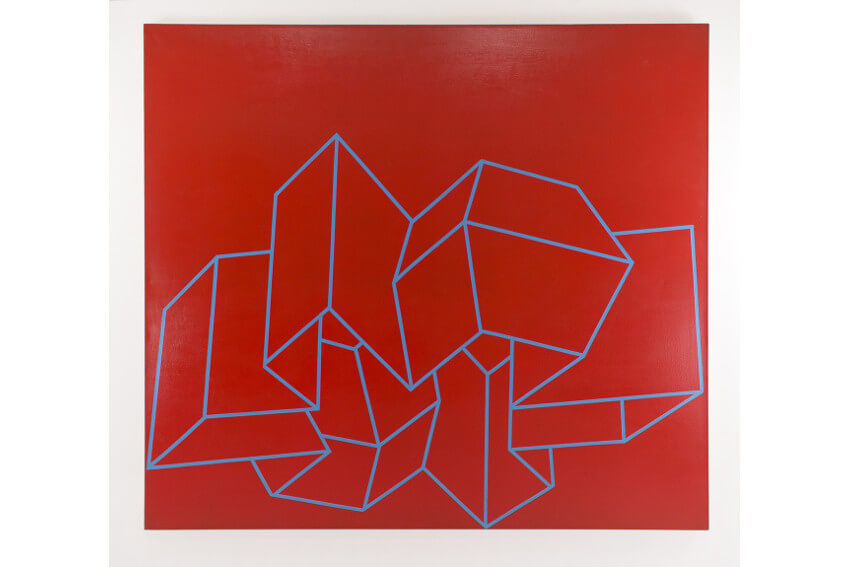

It was that spirit that emboldened Schapiro to move to California in 1967. There, she hit a turning point, when she became one of the first artists to discover the potential computers have to assist artists in their preliminary sketches. At the time, she was already gravitating toward hard-edged, abstract, minimal imagery in her work. She realized that by inputting her formal ideas into the digital visual world, she could quickly and endlessly make minor adjustments in perspective until the perfect image emerged. The paintings currently on view at Honor Fraser represent the result of this experimental process. Some of the works, like Thunderbird (1970), reveal the purely formal ways Schapiro was interacting with the computer. Other works, like Keyhole (1971), reveal her desire to use whatever tools are at her disposal to express the ideas pre-occupying her in the conceptual realm.

Miriam Schapiro - Keyhole, 1971, Acrylic and spray-paint on canvas, 71 x 106 in

Miriam Schapiro - Keyhole, 1971, Acrylic and spray-paint on canvas, 71 x 106 in

New Ways of Looking

This is not the first time these computer-aided paintings have been exhibited in recent years. They were shown at Eric Firestone Loft in New York in 2016, about a year after Schapiro died, under the title Miriam Schapiro, The California Years: 1967–1975. The difference in the two shows lies in their analytical focus. In New York, the exhibition examined these works in context with the aesthetic evolution that came right after. It examined the yonic imagery in paintings like Keyhole and Big Ox for the way it presaged the visual language Schapiro referred to as Central Core. It then explored how Schapiro completely abandon hard-edged abstraction in favor of a new style she invented called Femmage—an amalgam of feminine and collage. Femmage combined traditional painting techniques and surfaces with materials and techniques traditionally associated with femininity: for example, sewn elements on a canvas, or fabric pieces collaged onto a traditional surface. Femmage was an influential and pioneering aspect of the Pattern and Decoration movement.

Miriam Schapiro - Thunderbird, 1970, Acrylic on canvas 72 x 80 in

Miriam Schapiro - Thunderbird, 1970, Acrylic on canvas 72 x 80 in

Unlike the prior, extended version of this exhibition, the Honor Fraser show narrows the focus in order to offer spectators a purely formalist look at the work. It might seem odd to do this, or in some way diminishing. It would be easy for someone new to her work to see this show and misunderstand Schapiro. But in another way, this show lays the groundwork for what could be half a dozen other similar shows, which could each examine isolated moments in her career. It is generous to look at every facet of the work an artist does. If we only allow ourselves to dwell on the cultural meaning of the work without ever talking about its colors, lines, shapes, textures and processes, we deprive Schapiro of her full measure. It is obvious from these computer-aided paintings that such formal concerns were of importance to her. It is equally obvious she was a master of color and composition who could have spent a lifetime making important abstract work, if she had chosen to. After all, these paintings seem as fresh and contemporary as if if they were painted yesterday. But it is also exciting to think that these works represent a moment in time just before Schapiro dramatically altered art history by walking away from what was certain, and delving into the then unwritten story of feminist art.

Miriam Schapiro - Installation view, Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, 2017

Miriam Schapiro - Installation view, Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, 2017

Featured image: Miriam Schapiro - Installation view, Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, 2017

All images courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery

By Phillip Barcio