The Most Famous Abstract Paintings of Women

There is potentially so much more to a painting than what it reveals to our eyes. For example, what does it reveal to our minds? Some of the most famous realistic artworks are paintings of women. But what do those famous paintings of women communicate to viewers besides what is on the surface? They may communicate the mastery of their creators, but do they also communicate the inner essence of their female subjects? They may visually depict their times, but do they also extrapolate a cultural or historic understanding of gender? Do they just show us pictures of women in various situations, or do they explore the overarching meanings contained within situational feminine realities? Abstract paintings sometimes have an advantage when it comes to such matters since they inherently encourage viewers to search beyond what is on the surface. Here are ten famous abstract paintings of women that have helped us increase our understanding of femininity from the various perspectives of gender, history, culture and aesthetics.

Lee Krasner - Gaea

Have you ever wondered about the origin of the term Mother Nature? The ancient Greeks believed the creator of the universe was a feminine entity named Gaea. She gave birth to all things in existence, including all other gods and goddesses and the human race. Lee Krasner painted her monumental abstract painting Gaea in 1966. The painting marks an important evolution in her work, as she emerged from a particularly troubling time in her personal life. Its explosive color and expressive gestures embody a complex mixture of power, beauty, energy and harmony. As an abstract expression of the original and eternal feminine essence in the universe it ranks foremost among abstract paintings of women.

Lee Krasner - Gaea, 1966. Oil on canvas. 69" x 10' 5 1/2" (175.3 x 318.8 cm). Kay Sage Tanguy Fund. 212.1977. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lee Krasner - Gaea, 1966. Oil on canvas. 69" x 10' 5 1/2" (175.3 x 318.8 cm). Kay Sage Tanguy Fund. 212.1977. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

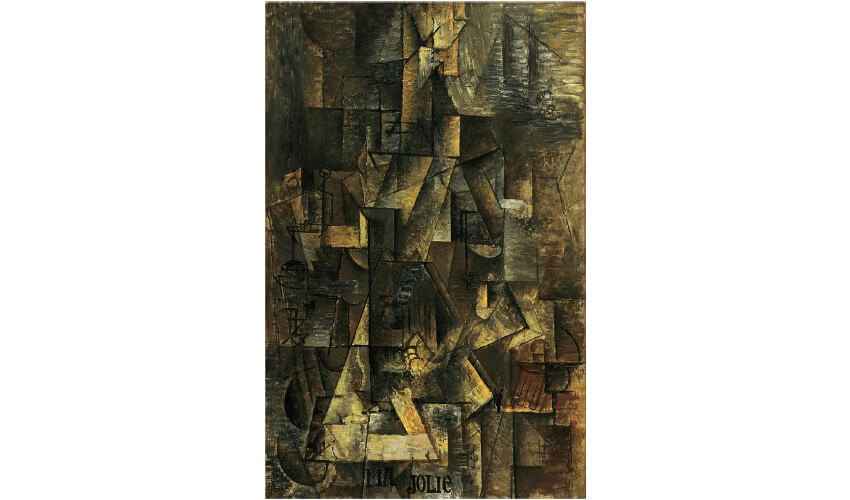

Pablo Picasso - Ma Jolie

Ma Jolie translates into My Pretty Girl, a popular French song when Picasso painted his Cubist painting of the same name. The phrase was also his pet name for his lover, Marcelle Humbert. As one of the earliest and most memorable expressions of analytic Cubism, this painting is famous for reasons that have little to do with its subject. But as a painting of a woman it is also enormously expressive. The dignified expression of nonchalance on the head in the upper right; the fleshy sensuousness of the toes; the musical notes and the hand strumming the guitar; the dizzying array of perspectives and sources of light; these all speak to the mix of whimsy, seriousness, respect and mystery that define the feelings Picasso expressed throughout his life for the feminine soul.

Pablo Picasso - Ma Jolie, 1911. Oil on canvas. 39 3/8 x 25 3/4" (100 x 64.5 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). 176.1945. © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso - Ma Jolie, 1911. Oil on canvas. 39 3/8 x 25 3/4" (100 x 64.5 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). 176.1945. © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

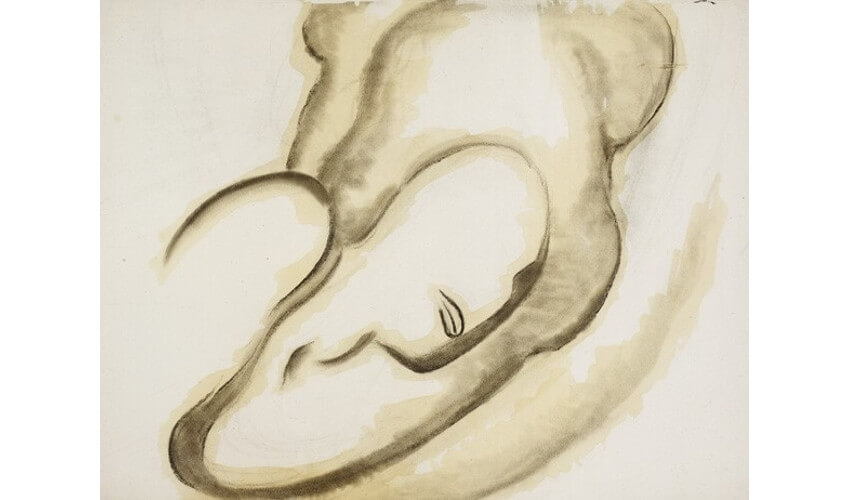

Georgia O’Keeffe - Abstraction (woman sleeping)

Georgia O’Keeffe stripped away everything she considered inessential. She sought to immerse viewers in a feeling. To do so she would often create large-scale, close-up images, enveloping viewers in the pictorial space. This painting is one of several similar abstract compositions O’Keeffe made of a woman sleeping. She drew it in charcoal then went over it in a wet brush, creating a dreamlike ethereality within the frame. It is an image of stoic, dignified grace, which speaks to something transitory and delicate, earthbound and yet eternal.

Georgia O Keeffe - Abstraction (woman sleeping), 1916. Charcoal and watercolor wash on paper

Georgia O Keeffe - Abstraction (woman sleeping), 1916. Charcoal and watercolor wash on paper

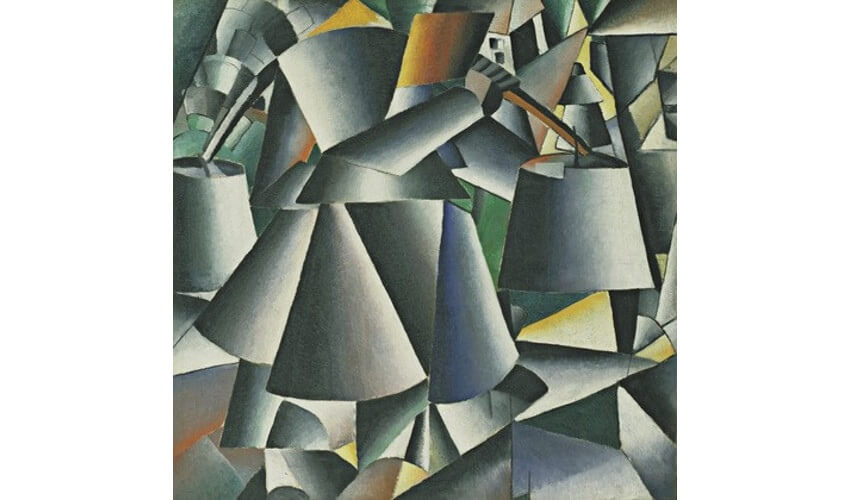

Kazimir Malevich - Woman with Pails: Dynamic Arrangement

Kazimir Malevich was a true believer in abstraction. A year after painting this painting, he invented his iconic style, Suprematism, which was devoted to a rejection of subject matter in lieu of universalities. This painting of a woman is not so much about a woman as it is about the formal qualities of the composition. What it communicates about femininity is subjective. But in the intent of the artist we find something democratic and, indeed, universal. The title, Woman with Pail, speaks to traditional feminine gender roles in working class Russia when Malevich made the work. That he chose this subject communicates that he was seeking a Utopian way to see the world not in divisive terms such as genders and social classes, but in terms of commonalities.

Kazimir Malevich - WWoman with Pails: Dynamic Arrangement. 1912-13 (dated on reverse 1912). Oil on canvas. 31 5/8 x 31 5/8" (80.3 x 80.3 cm). 1935 Acquisition confirmed in 1999 by agreement with the Estate of Kazimir Malevich and made possible with funds from the Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest (by exchange). 815.1935. MoMA Collection

Kazimir Malevich - WWoman with Pails: Dynamic Arrangement. 1912-13 (dated on reverse 1912). Oil on canvas. 31 5/8 x 31 5/8" (80.3 x 80.3 cm). 1935 Acquisition confirmed in 1999 by agreement with the Estate of Kazimir Malevich and made possible with funds from the Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest (by exchange). 815.1935. MoMA Collection

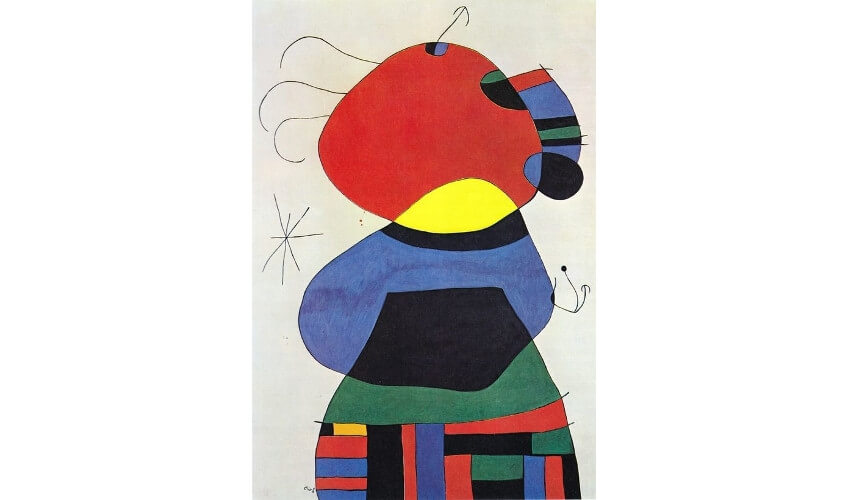

Joan Miró - Woman with Three Hairs Surrounded by Birds in the Night

Joan Miró never fully delved into complete abstraction. Instead he nurtured a unique aesthetic voice incorporating primitive iconography, reduced forms, and a vibrant, limited color palette. Through this idiosyncratic style he was able to communicate profundities in direct, simple, often whimsical ways. He often explored the theme of woman and children in his work. This abstracted image of a solitary woman expresses quiet strength and balance. It is meditative and suggests a figure in contemplation of everyday pleasantries. It is an image of security, solitude and harmony. In spite of its uncanny strangeness it evokes joy.

Joan Miro - Woman with Three Hairs Surrounded by Birds in the Night Palma/ September 2, 1972. Oil on canvas. 7' 11 7/8" x 66 1/2" (243.5 x 168.9 cm). Gift of the artist in honor of James Thrall Soby. 116.1973. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Joan Miro - Woman with Three Hairs Surrounded by Birds in the Night Palma/ September 2, 1972. Oil on canvas. 7' 11 7/8" x 66 1/2" (243.5 x 168.9 cm). Gift of the artist in honor of James Thrall Soby. 116.1973. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

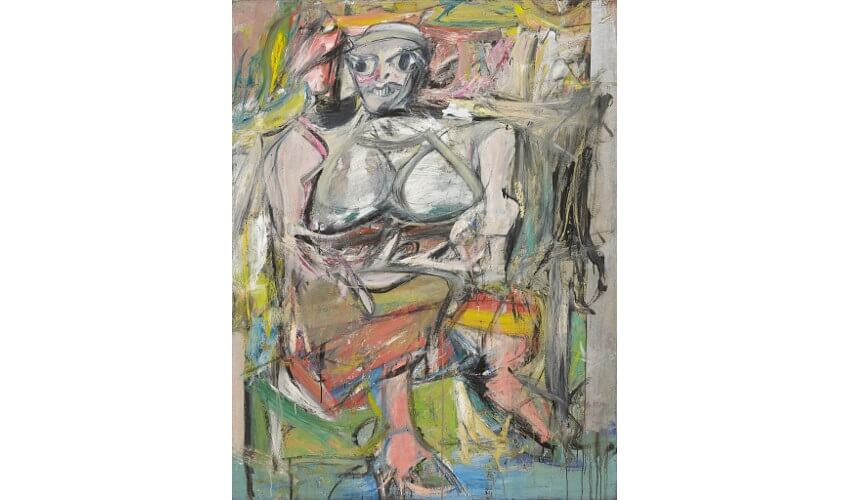

Willem de Kooning - Woman I

A leading Abstract Expressionist, Willem de Kooning specialized in emotive, energetic canvases. His technique was at once spontaneous and grueling. He painted aggressive, immediate layers then scraped them off, adding and eliminating over time. His many paintings of women have been interpreted as grotesque or angry, and even misogynistic. But he denied such associations, preferring to reflect on their primitive nature and the provenance they share with classical depictions of femininity. This most famous of his Woman paintings seems fitting as an example of that duality between the intent of the male artist when painting a woman and the way the end result of his expression can be interpreted by viewers. It offers us an iconic abstract image of a woman, as well as a jumping off point for a larger conversation about objectification and intent in art.

Willem de Kooning - Woman I, 1950-1952. Oil and metallic paint on canvas. 6' 3 7/8" x 58" (192.7 x 147.3 cm). 478.1953. MoMA Collection. © 2019 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Willem de Kooning - Woman I, 1950-1952. Oil and metallic paint on canvas. 6' 3 7/8" x 58" (192.7 x 147.3 cm). 478.1953. MoMA Collection. © 2019 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Maria Lassnig - Frühstück mit Ohr (Breakfast with an Ear)

No conversation about contemporary abstract female portraiture would be complete without mentioning the influence of Austrian artist Maria Lassnig. Her practice fluctuated between figuration and abstraction, but always orbited around a larger conversation of what she described in 1948 as body consciousness. Her painting Breakfast with an Ear is an iconic representative of the hundreds of self-portraits Lassnig painted, often containing only a portion of her body, relating to the body part she was most aware of at the time. This image addresses the larger social conversation of traditional gender roles, as the function of listener/nurturer is highlighted among images of electronic kitchen gadgets.

Maria Lassnig - Fruhstück mit Ohr (Breakfast with an Ear), 1967. © Maria Lassnig

Maria Lassnig - Fruhstück mit Ohr (Breakfast with an Ear), 1967. © Maria Lassnig

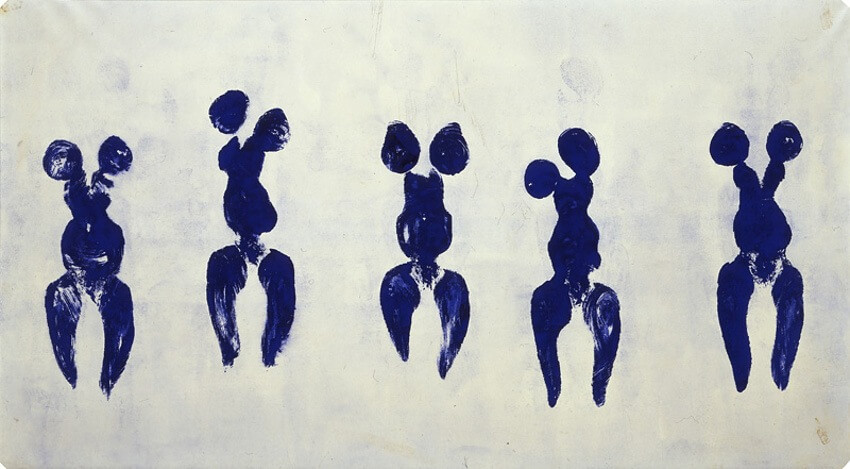

Yves Klein - Anthropométrie de l'époque bleue

As with many artworks by Yves Klein there is a conceptual layer to this painting that should be discussed. He did not paint it alone, but rather he participated in its creation as director. Anthropometry is the study of the physical dimensions of the human body. For his Anthropométrie series, Klein directed female assistants to strip naked and cover themselves in Yves Klein Blue, his eponymous hue. The assistants then physically imprinted their painted bodies onto surfaces, either spread out on the floor or mounted on the wall. This painting is in a sense an action painting. In another sense it is reportage, as it creates a physical record of an actual event. As an abstract image it offers a compelling suggestion of sensuality. It also suggests the X chromosome, a symbol of genetic femininity. From a conceptual standpoint it is potentially repugnant in its use of objectified female labor to complete a male dominated and prurient aesthetic vision.

Yves Klein - Anthropométrie de lépoquebleue, 1960. International Klein Blue on paper on wood. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Yves Klein - Anthropométrie de lépoquebleue, 1960. International Klein Blue on paper on wood. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Carrie Moyer - Tableau

Often the work of Carrie Moyer is politically charged, as in her Agitprop, graphic posters engaged in direct social activism and commentary. Other times, as in her abstract prints, it seems enveloped in metaphysical universalities. In her paintings those two poles often converge in graphically contained compositions combining what she calls “both illusionism and flatness.” Formalistically, Tableau possesses compositional gravity and shows a mastery of the sensuousness of the acrylic medium. Its sense of femininity is distinctly contemporary, simultaneously evoking something primitive and human and something futuristic and alien, anchoring it in an uncanny yet comforting present.

Carrie Moyer - Tableau, 2008. Acrylic, glitter on canvas. © Carrie Moyer

Carrie Moyer - Tableau, 2008. Acrylic, glitter on canvas. © Carrie Moyer

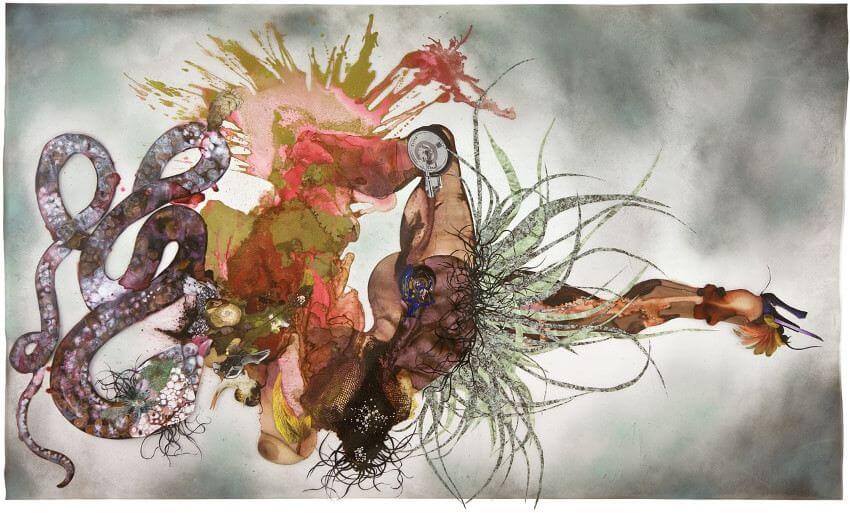

Wangechi Mutu - Non je ne regrette rien

It would be simplistic to say the paintings of Kenyan-born artist Wangechi Mutu are of woman, or about women. But they are filled with a language of forms communicative of physical femininity. Through her haunting images Mutu expresses the vast and varied experience of how the female body is encountered in global culture. This painting, titled after the Edith Piaf song Non je ne regrette rien (I regret nothing), simultaneously celebrates and objectifies the female body while evoking subconscious universalities through totemic feminine imagery.

Wangechi Mutu - Non je ne regrette rien, 2007. Ink, paint, mixed media, plant material and plastic pearls on Mylar. 137 x 221 cm. 54 x 87 1/8 in. Victoria Miro

Wangechi Mutu - Non je ne regrette rien, 2007. Ink, paint, mixed media, plant material and plastic pearls on Mylar. 137 x 221 cm. 54 x 87 1/8 in. Victoria Miro

Featured image: Georgia O Keeffe - Abstraction - Woman sleeping (detail), 1916, charcoal and watercolor wash on paper

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio