Abstraction and the Use of Different Types of Line in Art

Line is one of the formal elements of art. Along with elements like color, shape, texture and space, it is something aesthetic to contemplate aside from the subjective, interpretive components of an artwork. Discussing line in art is roughly equivalent to discussing aroma in wine, or flavor in food. It is one part of a larger aesthetic experience. Objectively, painters use line to outline shapes and create perspective, among other things. But there is also a theory that suggests various emotional states can be inspired by different types of lines in art. For example, a horizontal line supposedly conveys restfulness, since it mimics the position of a body in repose; a vertical line supposedly conveys spirituality, because it infers height; mixed horizontal and vertical lines supposedly convey stability; diagonal lines supposedly convey motion; and curved lines supposedly convey humanity and sensuality. It is unknown whether typical, uncoached viewers actually experience such feelings when looking at a painting; especially since subject matter can affect the messages supposedly being communicated by lines. But perhaps by looking at how various abstract painters have used line over the years we can discover whether there are indeed underlying truths connecting the emotional state of viewers and the aesthetics of line in art.

Spirituality and Line

In addition to being one of the first Western painters to pursue a completely non-representational form of painting, the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky was deeply concerned about conveying spirituality through his art. In 1912, he published a book called Concerning the Spiritual in Art. In it, he discussed his desire to attain through visual art what music had already attained through sound: the communication of universalities through an abstract aesthetic language.

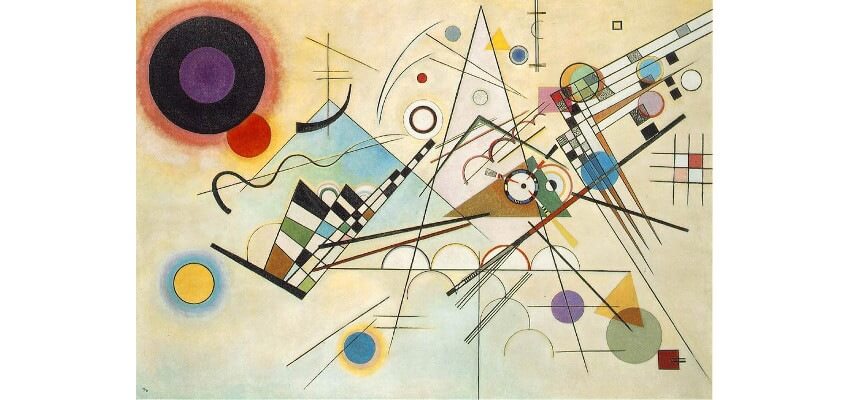

In 1926, after extensively testing his aesthetic theories, Kandinsky published another book called Point and Line to Plane. This treatise definitively stated his belief in the emotional impact of line in art. The paintings he created around this same time can be read as demonstrations of his theories. They use line formally to outline shapes, create dimensional forms, and to create perspective, and also to inspire emotional effect. An iconic example is the painting Composition VIII, which is admired for its sense of harmony and compositional balance. In it, crossed horizontal and vertical lines in the lower frame provide a stable foundation for the composition. Multiple diagonal lines create movement toward a vanishing point in the upper right. And curved lines introduce a lively, biological presence that is in flux.

Wassily Kandinsky - Composition VIII, 1923. Oil on canvas. 55 1/4 x 79 inches (140.3 x 200.7 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Wassily Kandinsky - Composition VIII, 1923. Oil on canvas. 55 1/4 x 79 inches (140.3 x 200.7 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Opposing Forces

Though his philosophy was much different than that of Kandinsky, the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian was also a believer in the communicative power of line. He believed that he could pare the language of painting down to its most bare essentials. He gradually reduced his visual tools until he arrived at a style that utilized only horizontal and vertical lines, and a severely limited color palette. Through this austere style, he felt he could communicate the underlying spiritual truth of the universe.

Mondrian rejected diagonal lines because he wanted to avoid perspective in order to attain a completely flat picture plane. And he rejected curves because he wanted to communicate something pure and universal. He believed horizontal and vertical lines alone, when used together, represented the pure, essential, opposing forces of the universe, such as masculinity and femininity, positivity and negativity, and stillness and motion.

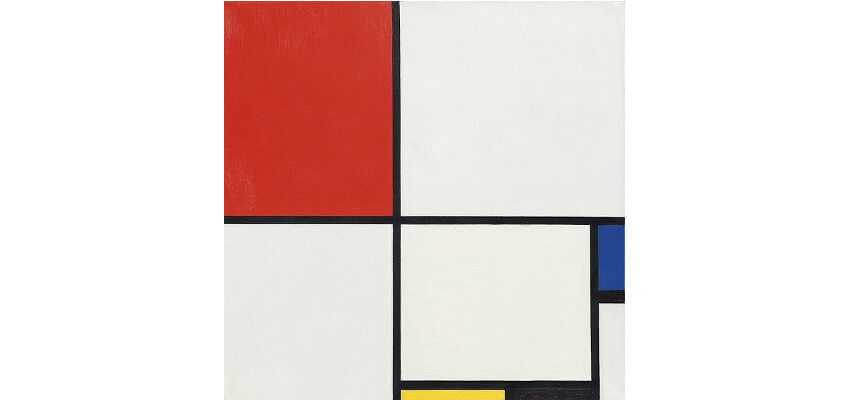

Piet Mondrian - Composition No III, with red, blue, yellow and black, 1929. Oil on canvas. 50 × 50.2 cm (19.6 × 19.7 in). Private Collection

Piet Mondrian - Composition No III, with red, blue, yellow and black, 1929. Oil on canvas. 50 × 50.2 cm (19.6 × 19.7 in). Private Collection

The Perfect Imperfect

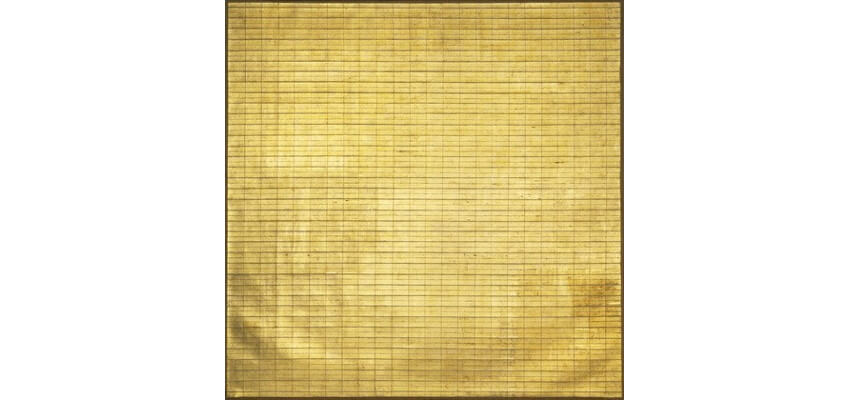

The Canadian born painter Agnes Martin employed an aesthetic approach that shared many similarities with that of Piet Mondrian. But Martin was seen as far more expressive and emotional than Mondrian. Both painters focused almost entirely on a combination of horizontal and vertical lines. But Martin painted hand-drawn grids that reveal her human touch. Even in their apparent precision, they contain subtle, minute imperfections.

Those imperfections take on the same function as a curved line, conveying something organic and essentially human. Though her work is perhaps more emotional, as is revealed by her titles, such as Friendship, Happiness-Glee, and Beautiful Life, she, like Mondrian, believed in the power of horizontal and vertical lines to express something harmonious and universal.

Agnes Martin - Friendship, 1963. Gold leaf and oil on canvas. 6' 3" x 6' 3" (190.5 x 190.5 cm). Gift of Celeste and Armand P. Bartos. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Agnes Martin - Friendship, 1963. Gold leaf and oil on canvas. 6' 3" x 6' 3" (190.5 x 190.5 cm). Gift of Celeste and Armand P. Bartos. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Color and Curves

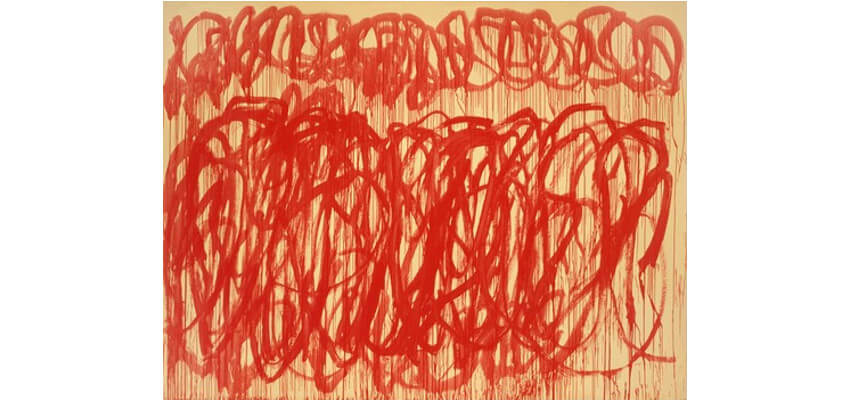

The oeuvre of the American painter Cy Twombly derives its iconic look from a visual language based almost entirely on color and line. His paintings are abstract, communicating intense feelings through their simplified palette and the energy and intensity of their scrawl. Their lines are mostly glyphic in nature, meaning their curved, sensuous nature resembles some kind of primitive writing.

Along with the glyphic lines, vertical lines also fill his images. But rather than being drawn, the vertical lines were created by drips made when his brush pushed against the surface. The verticals give the curved, glyphic forms a sense that they are rising. His painting Bacchus perfectly manifests this phenomenon, as its sensual curves evoke a sense of transcendence supported by the vertical drips.

Cy Twombly - Untitled (Bacchus), 2005. Acrylic on canvas. 317.5 x 417.8 cm. © Cy Twombly

Cy Twombly - Untitled (Bacchus), 2005. Acrylic on canvas. 317.5 x 417.8 cm. © Cy Twombly

Line and Illusion

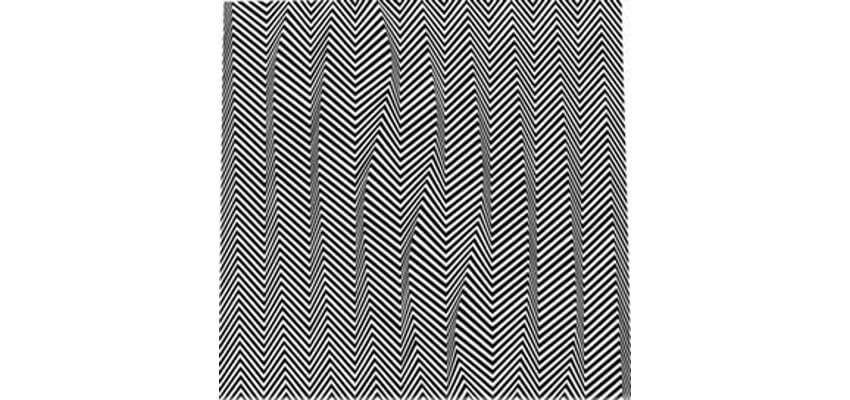

Line is a vital component of the work of Op Artists. And the paintings of Bridget Riley not only use line to evoke an emotional response from viewers. They also use line to create a physical response. The works Riley made in the 1960s were often said to make viewers feel sick, as though they were getting dizzy and nauseous from the sensation of motion created by the paintings.

In her 1966 painting Descending, Riley creates a sense of height from strong verticals, as well as a sense of perspective and movement from repeating rows of diagonals. Additionally, she creates a sense of sensual softness from the strategic placement of implied curves in the vertical lines. The lack of horizontal lines indeed also adds to the overall feeling that everything is off balance.

Bridget Riley - Descending, 1966. Emulsion on panel. 91.5 x 91.5 cm. © Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley - Descending, 1966. Emulsion on panel. 91.5 x 91.5 cm. © Bridget Riley

Contemporary Voices of Line

Many contemporary painters explore the communicative power of line in art. The Brazilian born painter Christian Rosa uses an idiosyncratic, sparse language of line that shares much with the work of Wassily Kandinsky. The American abstract painter Margaret Neill creates sensual, intuitional, curved linear compositions that speak in harmonious conversation with the work of Cy Twombly. Dutch painter José Heerkens uses horizontal and vertical lines in conjunction with color for the examination of space. And the French-American artist Peter Soriano uses line in ways that merge graphic sensibilities with something metaphysical and ethereal.

In addition to these we mentioned, scores of other abstract artists over the past century have explored the power of line to convey meaning and to inspire an emotional response. There is no way to prove whether they have achieved universal success. But there is no doubt that the formal aesthetic elements of art are at least capable of evoking emotional responses. And considered together, the works of these abstract artists we have mentioned present compelling arguments for the communicative power of line.

Featured image: Christian Rosa - Endless refill (detail), 2013, spray paint, pencil, tape, oil stick and oil on canvas, 180 x 200 cm

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio