The Lyrical Legacy of Magdalena Abakanowicz

In the heart of downtown Chicago, 106 massive, headless, iron figures occupy a grassy field at the south end of Grant Park, two blocks from the lakeshore. The figures seem to be walking in all directions, but are frozen in mid-step. Created by the Polish sculptor Magdalena Abakanowicz, these haunting forms uncannily encapsulate their surroundings: a place of towering steel structures and anonymous crowds, constant movement, yet constant traffic; a place caught in a never-ending negotiation between the organic and inorganic worlds. Abakanowicz passed away on 21 April 2017. Titled Agora, this permanent public installation is one of dozens of monumental outdoor works she completed in her career. All told, Abakanowicz brought into existence a population of nearly 1000 beings such as these. She sometimes referred to them as skins, suggesting they represent her own human shell: something peeled away from her, containing her life force, her personality, and her sacred spirit. Though she never fully explained their meaning, she once said they speak to “man’s horrible powerlessness against his biological structure.” They are obviously not alive, but neither do they seem fully dead. They belong to an immense oeuvre created by Abakanowicz over the course of a long and prolific career, one that confronted the condition of humanity in the contemporary world in a uniquely personal, often disturbing, and yet oddly comforting way.

The Dangers of Privilege

Magdalena Abakanowicz was born into a well-to-do family in Warsaw, Poland, in 1930. Her parents claimed an aristocratic heritage that stretched back to the Mongolian emperor Genghis Kahn. Their lineage was Tatar, one of five shamanistic, nomadic tribes that once controlled massive swaths of north central Asia. Like many Tatar people, the Abakanowicz family settled in what eventually became Russia. But because of their social status, they were forced to flee that country in the October Revolution of 1917. They moved to Poland, but then three years later found themselves once again in danger when the Soviets invaded. So they fled again, this time to the Polish city of Gdansk, where they established an estate and had a child, Magdalena.

But in only nine more years, world events intervened once more as the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939 caused the Abakanowicz family again to flee their home. In the midst of the social upheaval, Magdalena was separated from her parents for many months. Even after they were reunited it was still many years before the painful uncertainty and anxiety of war finally died down. And when Poland was liberated from the Nazis things hardly improved, as the Soviet Occupation inflicted upon the population widespread poverty and cultural repression aimed at total social homogenization.

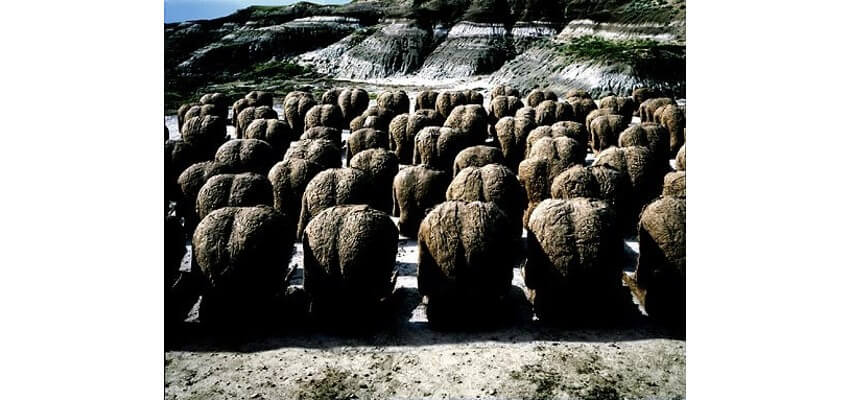

Magdalena Abakanowicz - 80 Backs, 1976-80, burlap and resin, image courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, Pusan, South Korea

Magdalena Abakanowicz - 80 Backs, 1976-80, burlap and resin, image courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, Pusan, South Korea

A New Beginning

Despite her troubled circumstances, Magdalena Abakanowicz demonstrated an early interest in art. The only type of art instruction allowed under the post-war Soviet rule was Soviet Realism, a style that demanded total adherence to realistic, nationalistic and socialist themes. In the face of the infuriating restrictions, Abakanowicz dedicated herself to learning technique, eventually mastering a range of disciplines that included painting, drawing, printing, sculpture, and weaving. Her discipline paid off in 1953, a year before her graduation from university, when Joseph Stalin died. With his death came a rapid process toward liberalization in Poland. Cultural restrictions were lifted and Polish artists were once again free to join their Modernist counterparts in the global avant-garde.

Abakanowicz threw herself into a visual exploration of her own mind. She became enthralled with the images and forms of nature, and developed an interest in materials that evoked the primitive natural world. She collected rope from the docks and unwound the fibers to create new forms, which she felt expressed something ancient and organic. Soon she began combining her fascination with nature with the shamanistic traditions of her family history, creating a visual language that expressed a simultaneous connection to the past and skepticism toward the modern world. By the mid-1960s, after more than a decade of experimentation, she arrived at an aesthetic position that conveyed a new mysticism and mythology through biomorphic abstract forms. Shockingly unique, it was both modern and primitive, personal and universal.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Rope Installation on a Baltic Dune, 1968, © Magdalena Abakanowicz

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Rope Installation on a Baltic Dune, 1968, © Magdalena Abakanowicz

The Abakans

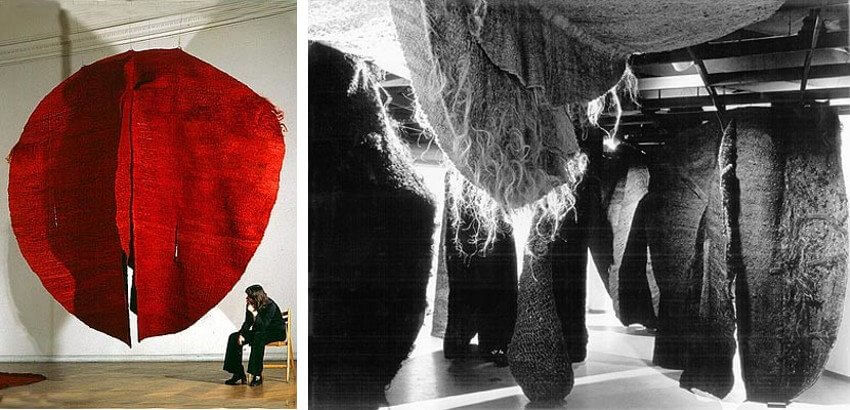

Abakanowicz first revealed her new aesthetic vision to the world in an exhibition in 1967, which included objects called Abakans: shamanistic, abstract entities she named after herself. Made from hand-dyed sisal, a type of natural fiber used in the manufacturing of rope, the Abakans were massive and imposing. The hand-woven objects were draped over metal frames and hung from the ceiling, resembling primitive sacred objects. They brought to mind animal pelts from the distant past as well as the tattered clothing and shantytowns of modern war refugees.

The scale of the Abakans was terrific. They extended all the way from ceiling to floor, and sometimes resulted in entirely enclosed environments ensconced by the forms. Many people perceived of the Abakans as stark and horrifying. They stood in dramatic contrast to the geometric Constructivist work that was being done by most of her Polish contemporaries at the time. Nonetheless they brought Abakanowicz instant recognition, and established her as a leading voice of the new Polish avant-garde.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Abakan Red, 1969, sisal weaving on metal support (left) and installation of Abakans in Sodertalie, Sweden, 1970 (right), © Magdalena Abakanowicz

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Abakan Red, 1969, sisal weaving on metal support (left) and installation of Abakans in Sodertalie, Sweden, 1970 (right), © Magdalena Abakanowicz

Organic Forms

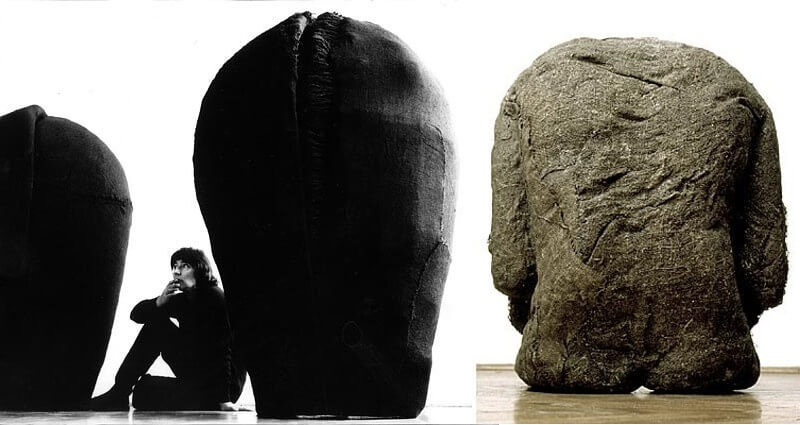

While the public was focusing on the monstrous qualities of the Abakans, Abakanowicz was focusing on one of their other essential qualities: their softness. In 1970, she abandoned these massive forms and instead used the same materials and techniques, and the guiding principal of softness, to begin fashioning biomorphic abstract ovoid objects and quasi-humanoid forms. She gave her new forms names like Heads and Backs, referencing their resemblance to human figurative elements. They were made of natural fibers and seemed to possess the same visual qualities as aged human skin. But the forms also contained a number of abstract qualities that invited deeper contemplation.

Most striking is the anonymity of these forms. If they are heads and backs, we should have some personal connection to them: some sympathy perhaps. But they are dismembered; disassociated from their humanity. They are only objects. We can appreciate them only for their materiality and their form. We can appreciate their color and texture, and their shape. We can appreciate the fact that each object was hand woven by Abakanowicz, made by the creator in her own image. There is something grotesque about them, and yet something Eden-like. They speak to the origin of our species, and also hint at its inevitable end.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Heads, 1972, Burlap and hemp on metal support, © Magdalena Abakanowicz and one of 40 Warsaw Backs, 1976/80, burlap, resin, each different, image courtesy of the Sezon Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Heads, 1972, Burlap and hemp on metal support, © Magdalena Abakanowicz and one of 40 Warsaw Backs, 1976/80, burlap, resin, each different, image courtesy of the Sezon Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo

Human Nature

Gradually, Abakanowicz added even more humanity to her figures. And simultaneously she also added more references to nature. A series called Seated Figures she created in the mid-1970s captures a moment in her aesthetic development when she seamlessly married both humanity and nature. The seated human forms are headless and anonymous, but they show a heightened degree of anatomic detail, such as rib cages, pectoral muscles and toes. Running through the forms are sinuous lines that at first seem to evoke veins or perhaps tendons. But soon the lines reveal themselves to be less like veins and more like vines. The forms then take on the presence of humanoid trees.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Seated Figures, 1974-79, burlap and resin, steel pedestal, eighteen pieces, image courtesy of Muzeum Narodowe, Wroclaw

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Seated Figures, 1974-79, burlap and resin, steel pedestal, eighteen pieces, image courtesy of Muzeum Narodowe, Wroclaw

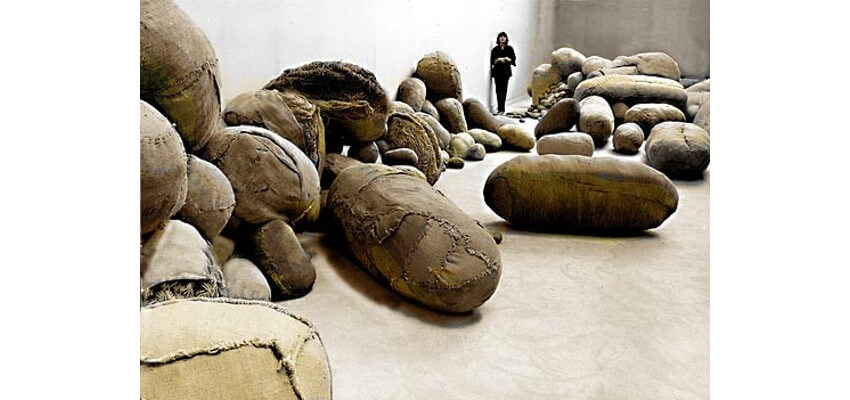

Next, Abakanowicz expanded on the notion of combining biomorphic elements with humanoid forms with the creation of an installation for the Venice Biennale called Embryology. This installation consisted of approximately 800 hand woven, ovular forms. The objects at first look like stones perhaps, or simple burlap sacks designed for carrying something. But considering the name Embryology, they cannot help but take on the character of eggs. They are soft, delicate shapes that contain some secret mystery. They protect whatever is inside of them and yet as we can see from many of the forms that are bursting open they are also fragile.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Embryology, installation at the 1980 Venice Biennale, Burlap, cotton gauze, hemp rope, nylon and sisal, © Magdalena Abakanowicz

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Embryology, installation at the 1980 Venice Biennale, Burlap, cotton gauze, hemp rope, nylon and sisal, © Magdalena Abakanowicz

Trees Are Brothers

Over time, the references to nature Abakanowicz included in her work became more overt, and sometimes even included actual natural elements. In the late 1980s, Abakanowicz created a series of sculptures in which sections of real trees were combined with metallic elements and strips of burlap. She called the series War Games. Because of the title, the pieces evoke unholy amputations of nature, as can so often be found in landscapes shattered by war. The burlap looks like a bandage wrapped around a severed limb, while the addition of metal extensions to these natural things makes the objects seem to have been modified to function in some new, absurd way through the addition of modern technology.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Zadra, from the War Games series, 1987-89, 91-93, wood, iron, burlap, image courtesy of the Hess Collection, California, USA

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Zadra, from the War Games series, 1987-89, 91-93, wood, iron, burlap, image courtesy of the Hess Collection, California, USA

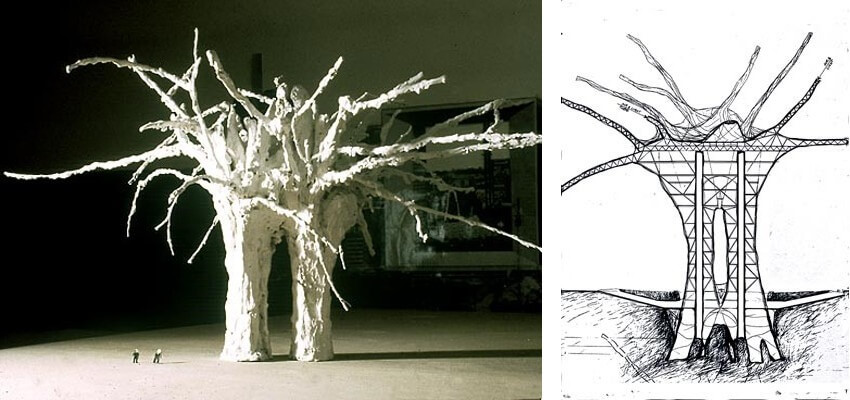

In 1991, Abakanowicz achieved what was perhaps her ultimate expression of the marriage of nature and human culture with her proposal to a design competition sponsored by the Parisian government. The competition sought new designs for structures to be built in La Défense, an expanded zone of development that allows for the ancient city to also include modern architectural achievements. Abakanowicz submitted designs for what she called Arboreal Architecture. The structures resembled massive tree trunks, which inside would be useful structures, and outside would be covered in vegetation.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Proposal for Arboreal Architecture for La Défense, Project for enlargement of the Grande Axe of Paris, 1991, organic-shaped buildings with vertical gardens, © Magdalena Abakanowicz

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Proposal for Arboreal Architecture for La Défense, Project for enlargement of the Grande Axe of Paris, 1991, organic-shaped buildings with vertical gardens, © Magdalena Abakanowicz

Humans Being

Although many of her most famous works were spectacular in their scale and sometimes shocking in their appearance, some of the most profound works Abakanowicz made speak the softest. One such piece is an outdoor installation in Lithuania of 22 concrete ovoid objects resembling eggs. The forms could easily be mistaken for naturally occurring boulders. They are quietly hopeful in their promise. Another soft-spoken piece of great impact is her installation of 40 partial human figures in Hiroshima preceding the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the nuclear attack on that city in World War II. The installation, titled Space of Becalmed Beings, speaks simultaneously to the calmness of the dead, as well as to a space dedicated to living humans who wish to find calmness within themselves, through contemplation of humanity, nature and art.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Space of Unknown Growth, 1998, 22 concrete forms, image courtesy Europos Parkas Collection, Lithuania

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Space of Unknown Growth, 1998, 22 concrete forms, image courtesy Europos Parkas Collection, Lithuania

In 2005, Magdalena Abakanowicz received a life achievement award from the International Sculpture Center in New York. In her speech accepting the award, she defined what sculpture is. She said, “With impressive continuity [sculpture] testifies to man's evolving sense of reality, and fulfills the necessity to express what cannot be verbalized. Today, we are confronted with the inconceivable world we ourselves created. Its reality is reflected in art.” In that statement, the purpose and meaning of her artwork is at least partially revealed. She worked to communicate what cannot be spoken with words: the truth of human feeling, the ancient, collective subconscious, and the undying connection humanity has with the laws of nature.

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Space of Becalmed Beings, 1992/93, 40 bronze figures from the Backs series, image courtesy Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima, Japan

Magdalena Abakanowicz - Space of Becalmed Beings, 1992/93, 40 bronze figures from the Backs series, image courtesy Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima, Japan

Featured image: Magdalena Abakanowicz - Agora, 2005-2006, 106 iron figures in Grant Park, Chicago, © Magdalena Abakanowicz

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio