Abstract Elements of Marcel Broodthaers Oeuvre

It makes sense when a poet becomes interested in abstract art. Both methods of expression are intentionally, joyfully indirect. Poets and abstract artists both challenge the obvious and the mundane in an effort to connect with something intuitive and universal. The Belgian poet Marcel Broodthaers spent the first 40 years of his life constructing his poetry out of words. Then in 1964, at the age of 40, he began making poetry out of other things: like surfaces, materials, products and spaces. The hundreds of uncanny objects and experiences Broodthaers brought into being over the course of his 12-year career as a visual artist were so full of romance, mystery and beautiful confusion that he made an immediate impact on the global art scene. Despite having no formal artistic training, by the time he died at age 52 Broodthaers had created a body of work that changed the way many artists, collectors and museums perceive of their role within the world of art.

Truth and Shadows

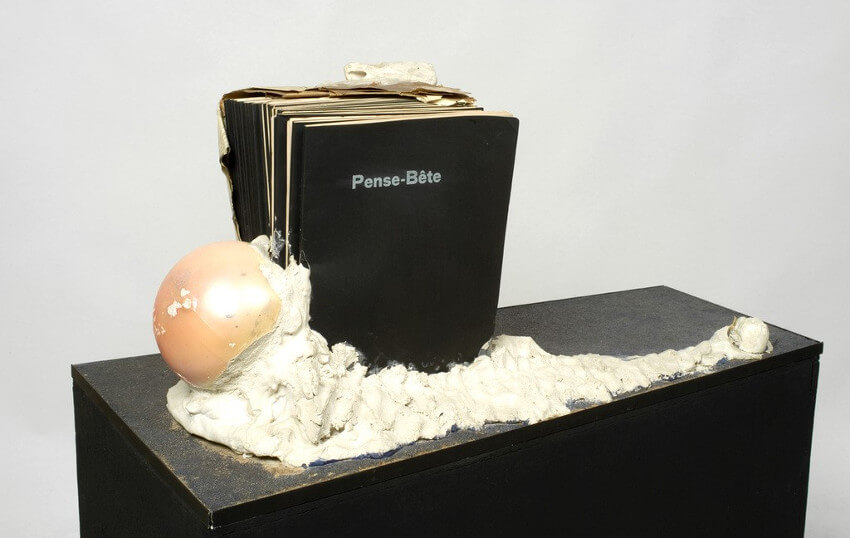

One of the poems from Marcel Broodthaers’ book Pense-Bête begins, “The truth. The shadows. The lizard flees with the lizardess. The stone is naked.” The words evoke wonder about the secret source of meaning; what’s real and what’s illusion, what’s lasting and what’s fleeting. The phrase Pense-Bête translates as “memory aid.” And that’s also the name of Broodthaers’ first art object, which consists of dozens of unsold copies of Pense-Bête encased in cement. The object itself is poetic. The cement renders the books unreadable. Are there still poems inside? If we can’t read them, does it matter if they’re there? Do unreadable poems still possess meaning? Are these books or symbols? Or neither? Is the composition abstract, entirely open to interpretation?

Another possible reading of Pense-Bête could be that the cement resembles a giant, broken egg. Maybe the egg contained the books, the “brain children” of the poet. Or maybe someone threw the egg at the books, an insult against the poems. Or, it’s a statement about an egg as a container. Cement is also a container. Books are containers. Memories are containers. Perhaps some meaning lies in the idea of containment. Or perhaps that’s just a shadow.

Marcel Broodthaers - Pense-Bete, 1964, Books, paper, plaster, and plastic balls on wood base, 11 4/5 × 33 3/10 × 16 9/10 in, 30 × 84.5 × 43 cm, © 2018 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

Marcel Broodthaers - Pense-Bete, 1964, Books, paper, plaster, and plastic balls on wood base, 11 4/5 × 33 3/10 × 16 9/10 in, 30 × 84.5 × 43 cm, © 2018 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

Marcel Broodthaers Contained

More definite clues to Broodthaers’ poetic visual language come from a couple of works he made in 1965. His assemblage White Cabinet and White Table features an antique cabinet and table filled and covered with broken eggshells. The primordial containers of life have been emptied of what they once contained, so now their only content is air. The cabinet, hanging on the wall, is a container full of empty containers. The table, sitting on the floor, supports more empty containers. Is it symbolic that the two pieces are antiquated and full of emptiness, and that the promise of life has been lost? Is it significant that one piece hangs on the wall and the other sits on the floor? Is Broodthaers referencing painting and sculpture? Is this a witty, symbolic critique, or are the eggs, the furniture, and the color white simply abstractions?

For his work Triomphe de moule I (Triumph of mussel I), Broodthaers again featured the language of containment. The artist overfilled a cooking pot with empty mussel shells. In French, the word moule has at least two meanings: mussel, and mold. A mussel contains a creature. A mold contains a form. A sculpture is a form, and often comes from a mold. The title could literally refer to the triumphant number of mussels. Or it could refer to the triumph of the pot, itself a mold, in containing so many mussel shells. Or it could reference the aesthetic object as a triumph of sculpture. Or possibly, as with the cement, the books, the eggs, the cabinet and the table, perhaps the work is an abstract reference to potential, and the fluctuating states of fullness and emptiness. It’s hard to be sure what Broodthaers’ intention was. As with the artist Arman and his accumulations, he uses large numbers of like objects in such a way that they are re-contextualized from their original purpose, becoming purely aesthetic occupants of space, open to interpretation.

Marcel Broodthaers - White Cabinet and White Table, Painted furniture with eggshells, Cabinet 33 7/8 x 32 1/4 x 24 1/2in, 86 x 82 x 62 cm, table 41 x 39 3/8 x 15 3/4in, 104 x 100 x 40 cm (Left), 1965, and Triomphe de moule I (Triumph of mussel I), 1965, Painted and enameled iron alloy; mussel shells with paint, 18 1/2 x 19 5/8 x 14 5/8 in, 47 x 49.8 x 37.1 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art(Right), © 2018 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

Marcel Broodthaers - White Cabinet and White Table, Painted furniture with eggshells, Cabinet 33 7/8 x 32 1/4 x 24 1/2in, 86 x 82 x 62 cm, table 41 x 39 3/8 x 15 3/4in, 104 x 100 x 40 cm (Left), 1965, and Triomphe de moule I (Triumph of mussel I), 1965, Painted and enameled iron alloy; mussel shells with paint, 18 1/2 x 19 5/8 x 14 5/8 in, 47 x 49.8 x 37.1 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art(Right), © 2018 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

The Poetry of Knowledge

Much of Broodthaers’ artistic oeuvre focused on words and their apparent meaning or lack thereof. The Farm Animals presents pictures of different kinds of cows, each with the brand name of a popular automobile printed beneath it. And for his piece The White Room Broodthaers constructed a full-sized replica of his Brussels art studio, covering the white walls with seemingly random and meaningless bursts of black text. Part of the fun of interpreting these works comes not just from the words Broodthaers uses, but also from the whole idea of words. Words are abstract. A word isn’t the thing it represents any more than a picture is, a point made by one of Broodthaers’ influences, René Magritte.

By poetically combining words and objects, Broodthaers exploited the essential vulnerability of the mind. The artist used the two types of intelligence against each other. What’s called Crystallized Intelligence helps us understand what’s objectively real about the world, such as the knowledge that fire is hot. Fluid Intelligence helps us apply and interpret the reality that we supposedly know. Broodthaers created an abstract aesthetic that inhabits the middle ground between these two intelligences, utilizing the visual language of crystallized reality in ways that baffles our fluid attempts to interpret it.

Eagles Wings

One of Broodthaers’s most influential aesthetic creations was his conceptual museum called The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, which he started in 1968. The museum had no permanent location or permanent collection. Rather it manifested as a series of traveling exhibitions, each one highlighting part of the museum’s alleged collection. These exhibitions didn’t include Broodthaers’ art. They consisted of other artists’ work, prints, books, relics and historical objects related to eagles.

Broodthaers museum caused many in the art world to question the relationship between art, artists and museums. The sculptor Richard Serra once said, “Art is useless.” But if art has no function, what’s a museum’s function other than to house useless things? But if we read the eggshells, mussels, words and objects in Broodthaers’ other works as abstract symbols, why not do the same with his museum? Maybe the Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles wasn’t a statement so much as the installation equivalent of a Kazimir Malevich composition: an assortment of re-contextualized forms compiled in a meaningless arrangement in space.

Regardless of his intention, the poetry and wit of Broodthaers legacy is undeniable. He took fragile meaning, something as delicate as an eggshell, and turned it into something archival. Whatever its purpose or use, his oeuvre now functions as inspiration, the ultimate container for all of our beliefs about what abstract art can be.

Featured image: Marcel Broodthaers - Tableau et tabouret avec oeufs (Painting and Stool with Eggs), © 2018 Estate of Marcel Broodthaers / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio