Groundbreaking yet Forgotten - The Art of Mark Tobey

This summer the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, Italy, is showcasing the first major European retrospective of the paintings of Mark Tobey in more than 20 years. Titled Mark Tobey: Threading Light, the exhibition includes 66 major works created by Tobey between the late 1920s through the early 1970s. The selection of work endeavors to highlight the various evolutions Tobey went through in his career as he searched for ways to express the universalities of human existence. After beginning his career as a commercial illustrator and portrait artist, he transitioned into painting in his 30s. He started with figurative work, but soon found himself engaged in the Modernist conversation about how to develop new aesthetic points of view. His eventual achievements in this respect were enormous, which makes it all the more odd that so many people today have either completely forgotten about Tobey or have never heard of him. Not so long ago, he was considered one of the most important and influential painters in the world. That fact makes the timing and location of this current exhibition particularly fitting. Its run is timed to coincide with the 2017 Venice Biennale, a subtle reminder that it was at a previous Venice Biennale in 1958 that Mark Tobey made history. Tobey represented the United States in that fair alongside Mark Rothko. But while Rothko may enjoys far more fame today in the United States, it was a Tobey painting titled Capricorn that won the 1958 City of Venice Prize for painting—the first time, incidentally, since the inaugural Venice Biennale in 1895 that the gold prize went to an American painter.

An Open Mind

Mark Tobey was born in the midwestern American town of Centerville, Wisconsin, in 1890. Though he soon left Wisconsin, he fondly remembered it and frequently referenced its scenery in his early paintings. But unlike many American abstract painters in his generation who favored living and working entirely in New York, for much of his adult life Mark Tobey chose to live and work in Seattle. It was perhaps that fateful choice that led to much of the freedom and open mindedness that defined his development as an artist. Another frequent Seattle resident, the martial artist Bruce Lee, had a similar outlook on life as Mark Tobey. Lee founded an approach to fighting called Jeet Kun Do, which he described as the “style of no style,” meaning a fighter should reject dogma and be open to learning everything possible then keep whatever works and discard whatever does not. The “style of no style” grew out of teachings Lee first learned while studying Zen Buddhism, and it is strikingly similar to the approach Mark Tobey developed toward painting many years earlier.

Tobey first traveled to Asia in the 1930s. That trip came during a time when he was struggling as a painter to figure out what to do about space. He could not decide whether to attempt to achieve depth and dimension in his works or to abandon it and instead embrace flatness. While visiting Japan, Shanghai and Hong Kong, he gained a new and profound understanding of the different ways Asian artists have treated space in their work throughout history. He had earlier already learned the techniques of Chinese calligraphy while living in Seattle in the 1920s, but this trip exposed him to a more complete awareness of how writing and symbology fit in to the larger aesthetic approaches of Asian art. This epiphany opened Tobey up to the idea that he should not just study the way his culture makes art, but should rather open himself up to learning everything possible about the way all different cultures make art.

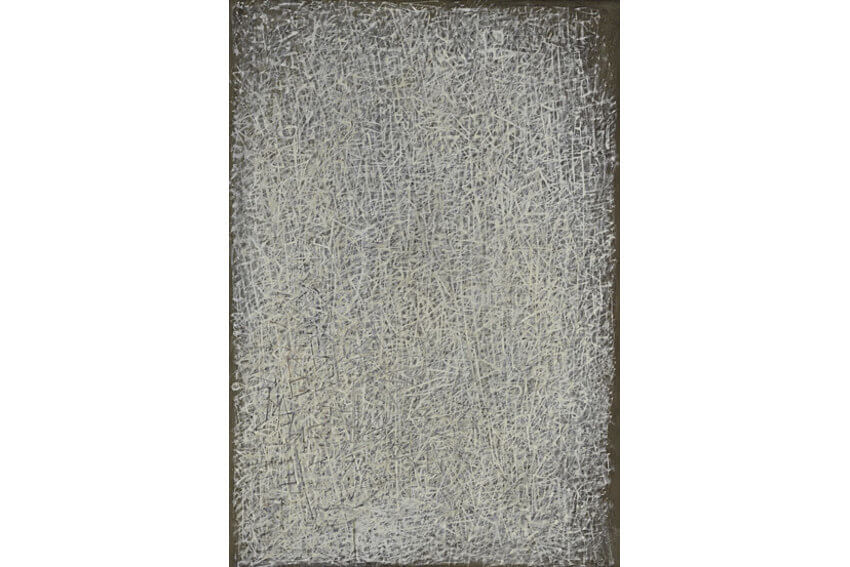

Mark Tobey - Crystallizations, 1944, Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Mabel Ashley Kizer Fund, Gift of Mellita and Rex Vaughan, and Modern and Contemporary Acquisitions Fund

Mark Tobey - Crystallizations, 1944, Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Mabel Ashley Kizer Fund, Gift of Mellita and Rex Vaughan, and Modern and Contemporary Acquisitions Fund

All Over Painting

Shortly after returning from Asia, Tobey created one of his most influential paintings, titled Broadway. It is a somewhat figurative expression of the shapes, colors and lights of the famous street in New York. But it is transformative in its approach. The composition comprises hundreds of tiny, gestural, white marks. The resemblance to writing is clear, but the markings do not spell anything concrete, nor do they directly represent real world shapes. They are evocative and poetic. The painting is seen today as the precursor of an aesthetic style Mark Tobey would continue to pursue variously throughout his career, which he called “white writing.”

Broadway was painted in 1936. In the following years Tobey continued to develop the approach that defined that work. He abstracted his calligraphic markings beyond recognition and soon abandoned all figurative shapes. He became committed to communicating feeling more than just images. Most importantly he made a point of covering the entire surface of his canvases with compositions that did not give preferential treatment to any one particular area of the surface. That idea was highlighted later by the art critic Clement Greenberg when he described the “all-over pictures” Jackson Pollock was making in the 1940s. But it was Mark Tobey, whose paintings Pollock had seen years earlier, who pioneered this approach.

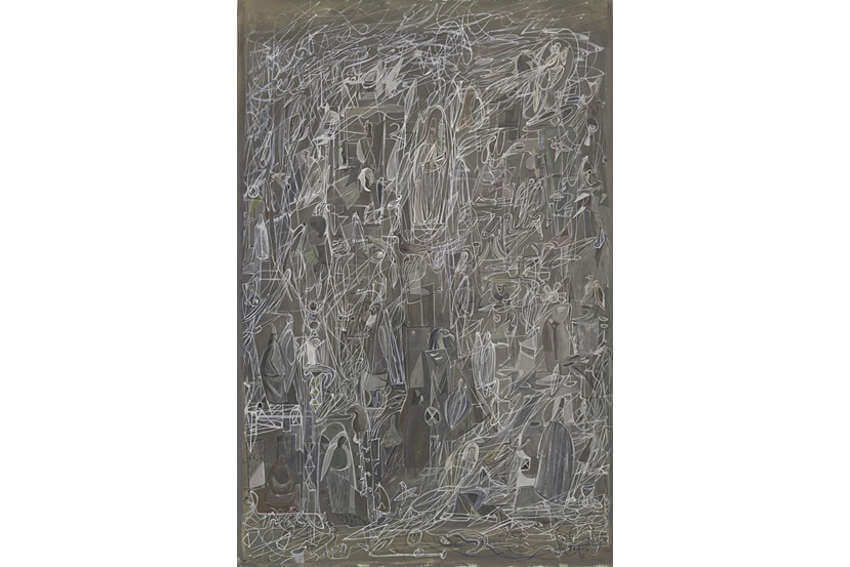

Mark Tobey - Threading-Light, 1942, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Mark Tobey - Threading-Light, 1942, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The School of No School

Mark Tobey was certainly acquainted with Jackson Pollock and all of the other artists of the New York School. Works by Tobey were included in the 1946 exhibition Fourteen Americans at the New York Museum of Modern Art, an exhibition that also included Arshile Gorky and Robert Motherwell. But whereas those New York artists and their cheerleader Greenberg embraced the myth that they were part of the emergence of a type of inherently American art, Tobey rejected that concept. He insisted that art should not be defined in such narrow terms, or be confined by petty notions such as nationalism, politics, culture or geography. He refused to associate himself with the idea of the New York School, even though his work so clearly was a precursor to the ideas of its members.

Instead, Tobey adopted the same approach Bruce Lee later described. Call it the School of No School. Tobey traveled, read, experimented, learned as many different approaches as he could and then kept what worked and abandoned what did not. He even studied Zen Buddhism and mastered Japanese Sumi-e (black ink) painting. His openness and his searching are evident in the selection of works included in Mark Tobey: Threading Light, which even includes some of his Sumi-e works as well as various paintings that evolved from the technique, such as City Reflections, which directly incorporates splattered black ink, and Lumber Barons, which more delicately references Sumi-e in a way more connected to white writing.

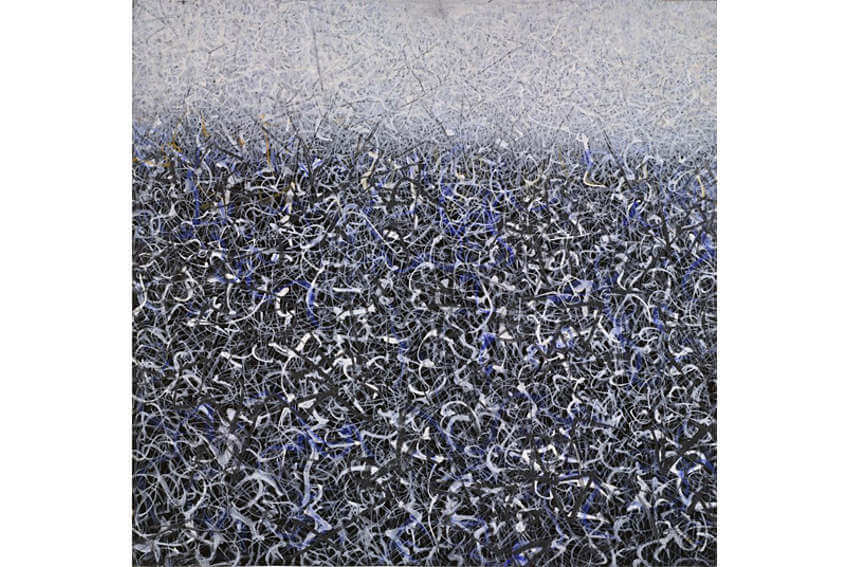

Mark Tobey - Wild Field, 1959, The Museum of Modern Art, NY, The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection

Mark Tobey - Wild Field, 1959, The Museum of Modern Art, NY, The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection

A Universal Aesthetic Language

Aside from his contempt for nationalistic or regional labels, another major reason some critics believe Mark Tobey was ultimately forgotten by many writers of American art history has to do with his overt spirituality. Not to say that the American art world is an unspiritual place: obviously that is not true. But the particular brand of spirituality Mark Tobey espoused put him at odds with just about everyone, from artists, curators, gallerists and critics to people outside the world of art. Tobey belonged to a faith known as Bahá'í. The core belief of the monotheistic Bahá'í religion is an abiding respect for the value and worth of all human religions, and the goal of members is lasting peace through the unity of all people. That may not sound controversial to a sensible person, but the religion also insists that all religions came from a single divine source, and that all prophets are equal manifestations of the same godhead, beliefs that contradict the core tenets of almost every major religion, especially Christianity, Judaism and Islam.

As far as the American art world goes, it is fine to talk about the spirit, as Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian certainly did; and it is good to talk about universality, as Agnes Martin and so many others did; and it is great to talk about transcendence and contemplation as Mark Rothko did. But the word religion scares people. American institutions avoid things that might threaten them commercially. And though things may be different now, in the mid-20th Century overt religious agendas were not generally considered good for business. But Mark Tobey never cared about that. He did not hesitate to address his religious beliefs, and quite frequently he professed that it was his goal to use his art as a way to contribute to the creation of a universal language that could help humanity achieve unity and peace. But of course whether this is the reason he has been neglected in the U.S. is nothing but speculation. Happily, despite the snub from his homeland, Tobey enjoyed a long and fruitful career elsewhere, especially in Europe, where he was revered in his lifetime and where he is today considered to be the progenitor of movements like Tachisme and Art Informel. Mark Tobey: Threading Light is on view at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, Italy, through 10 September 2017.

Mark Tobey - World, 1959, Private Collection, New York

Mark Tobey - World, 1959, Private Collection, New York

Featured image: Mark Tobey - Untitled, Sumi Drawing (detail), 1944, The Martha Jackson Collection at The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

By Phillip Barcio