Martin Barré, The Forgotten Abstract Artist, at Centre Pompidou

The retrospective Martin Barré, on view from 14 October 2020 through 4 January 2021 at the Center Pompidou, offers the most comprehensive look yet at the always-evolving career of this enigmatic artist. Yet, despite his local fame (20 of the works in the show are from the permanent collection of the Pompidou) there will no doubt be many viewers from outside of France who have no idea who this artist is. If they look at his work only from a contemporary point of view, they may even wonder why they should care. Barré did not address any particular social or political concerns in his work. In fact, his paintings often seem to have no content at all, nor do they make much of a splash as objects. Indeed, Barré (1924 — 1993) was also frequently dismissed in his own time. Nonetheless, to many of us there is something undeniably appealing about his work. Simple, and even at times simplistic, his paintings are honest, fun, and unmistakably human. Barré made paintings that barely seem to be paintings, and I feel like that was the point. As the Pompidou retrospective clarifies, Barré went through at least five major shifts in his visual style. These shifts were perhaps inconsequential in art historical terms, but that does not diminish the truth his evolution consistently revealed—that the only obligation an artist has is to their own curiosity. In our age, when every artist is expected to be able to mount a vigorous academic, social, and political defense of their work, Barré might seem less than serious. But that was always the case, even half a century ago. He never fit in. By following his own interests, Barré became to his French admirers what Agnes Martin is to the Americans: a prophet of Minimalism as both an aesthetic method, and as a path towards self knowledge.

The Proto-Minimalist

Born in Nantes, in western France, in 1924, Barré reputedly walked all the way to Paris as an aspiring, 19-year old artist. The 376 km trip took him five days. For the next decade he studied in various art academies and experimented with various methods and visual languages. He soon determined that the only way forward for him was abstraction, and the main abstract concern that interested him was the relationship between the painted image and its ground (or prepared surface). Barré was curious about what could constitute a painting; what made paintings distinct; and what could count as content in a painting. He did not think he was a pioneer in asking these questions. On the contrary, referring back to a painting created half a century earlier, he said, “All painting seems to me to lead to and set off from Malevich’s black square on a white ground.”

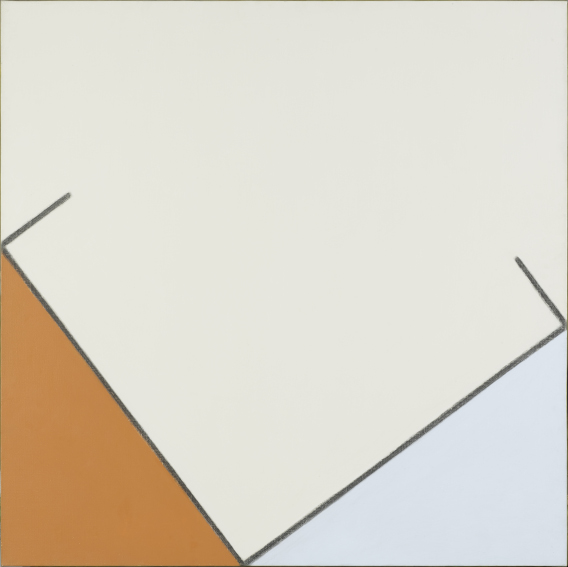

Martin Barré - 86-87-120x120-E, 1986 - 1987. Acrylique sur toile. 120 x 120 cm. Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris. © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Bertrand Prévost/Dist. RMN-GP © Martin Barré, Adagp, Paris 2020

In several of his earliest abstract paintings, Barré also deployed the square to explore the relationship between image and ground. Rather than painting the squares, he blocked off the shape, delineating its emptiness with the painted space around it. The simple question these paintings propose is whether emptiness can be content. Next, he simplified his method even further, taking inspiration from spray painted graffiti he saw around Paris. Perceiving spray paint cans as perfect extensions of the hand of the artist, he made a series of paintings that look like nothing more than sprayed lines atop the prepared surfaces of canvases. Sometimes he sprayed lines in a pattern. Other times he sprayed only a tiny line across one corner of a canvas. Sometimes he painted squiggles. Other times he hung multiple canvases on a wall and continued one line from canvas to canvas. The minimal quality of these works stood out in contrast to the works his contemporaries were doing in the 1960s, lending Barré his reputation as being anti-culture, and a proto-Minimalist.

Martin Barré - 57-100x100-A, 1957. Huile sur toile. 100 x 100 cm. Collection privée, Paris; courtesy Applicat-Prazan, Paris. © Martin Barré, Adagp, Paris 2020 / Photo: Art Digital Studio

Simple Questions

In the 1970s, Barré took a four year break from painting to explore what he called photo-conceptualism. This period of his career is not frequently explored in his gallery exhibitions. I sometimes wonder, if art could not be bought and sold, how would that change the way people write about it? Usually, I think they would write less. In the case of Barré, I believe they would write more, especially about this hiatus. It may not have generated any products to be sold in art stores, but it profoundly affected the way Barré understood his central question about image versus ground. When it ended, his paintings became much more dense, with sketched grids supporting painted hatch marks, which are in turn veiled in layers of clear wash. These works are still geometric, going back to Malevich and his squares, but they are quite complex, and come closer than anything Barré did before to embracing what most viewers would consider content.

Martin Barré - 60-T-43, 1960. Huile sur toile. 81 x 330 cm (quadriptyque). Collection privée. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York / Photo: Ron Amstutz © Martin Barré, ADAGP, Paris 2020

In his late years, Barré once again refined his visual language, this time creating a series of hard edge geometric works that suggest his affinity with another early abstractionist: Piet Mondrian. These, his final paintings, with their clean, flat compositions, are sometimes talked about as if they are rejections of his earlier works, which are more raw. However, they do not seem so far removed. They show lines painted on a ground in order to delineate space. The painted areas interrogate the ground, raising questions about which part of the painting the image is. As all of his previous paintings did, these final works ask what is more important: the content of a painting, or its support? To me, this is not only a question about painting, but also an existential question about being a painter. It asks what is valid in the eyes of others; what should get attention; and what is worth our time—simple questions maybe, posed by simple paintings, but their simplicity makes space for us to learn about ourselves.

Featured image: Martin Barré - 60-T-45, 1960. Huile sur toile. 192 x 253 cm (quadriptyque). Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris. © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Bertrand Prévost/Dist. RMN-GP © Martin Barré, Adagp, Paris 2020

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio