Turbulent Life and Art of Martin Kippenberger

This year will mark the 20th anniversary of the death of Martin Kippenberger. A leader in a revolutionary generation of German artists to emerge in the 1970s, Kippenberger died on 7 March 1997 at the age of 44, from liver failure after decades of relentless partying. When he died he was known on several continents for things like taking his pants off in public and insulting people, but his art was barely known outside of avant-garde subcultures. Since his death, curators, collectors, critics and historians have revisited his work. Retrospectives at the Tate Modern, Los Angeles MoCA, and New York MoMA have constructed an image of Kippenberger not as a restless, drunken wild man, but as a masterful painter, a prolific multi-media experimenter, and a globally influential impresario. In some ways the dual life of Martin Kippenberger heralded our current culture of celebrity artists and alternative truths. Looking back at his oeuvre we see abstract elements within it that help us understand the madness that consumed him, and that today has become part of the norm.

The Young Martin Kippenberger

Born in Dortmund, Germany, in 1953, Martin Kippenberger was part of the generation of artists unwittingly charged with the task of re-imagining German art in the aftermath of World War II. His father was the director of a coal mining company. Kippenberger took his first art classes as a child after his father moved the family to the Black Forest region for work. But Kippenberger infamously boycotted those art classes almost as soon as he started them, to protest his teacher giving him only the second highest grade in the class. That mix of confidence and audacity would stay with him throughout his artistic career.

The double curse Kippenberger suffered as a child was that he was immediately talented at everything he took up, and yet nothing he tried seemed adequate to him as a complete mode of expression. As a teenager, he experimented with dancing and various practical creative trades, like window decorating. But finding no purchase for his efforts he gravitated toward other pastimes, like the use of mind-altering substances. By age 16 he was addicted to drugs and had to enter a recovery program. But then after recovering, he made his way to Hamburg where he fell in with a group of similarly restless, creative young people with whom he began taking classes at the Hamburg Art Academy.

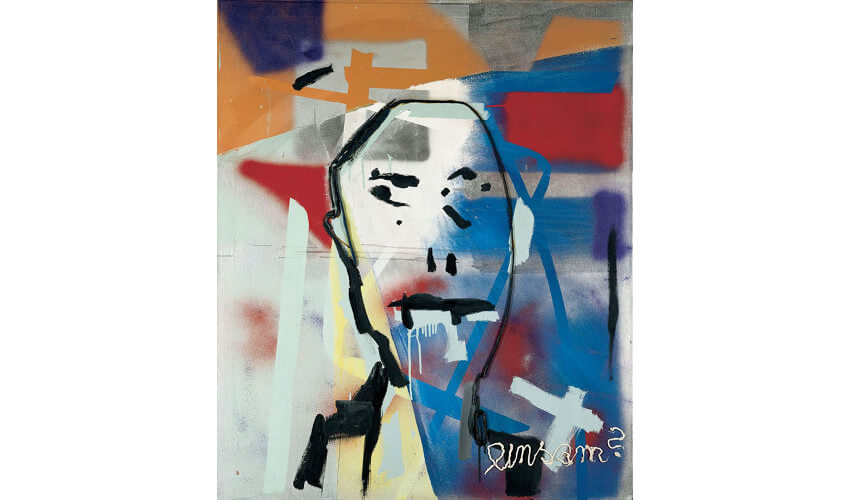

Martin Kippenberger - Lonesome, 1983. Oil and Spraypaint on Canvas. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Martin Kippenberger - Lonesome, 1983. Oil and Spraypaint on Canvas. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Multi-Disciplinary Roots

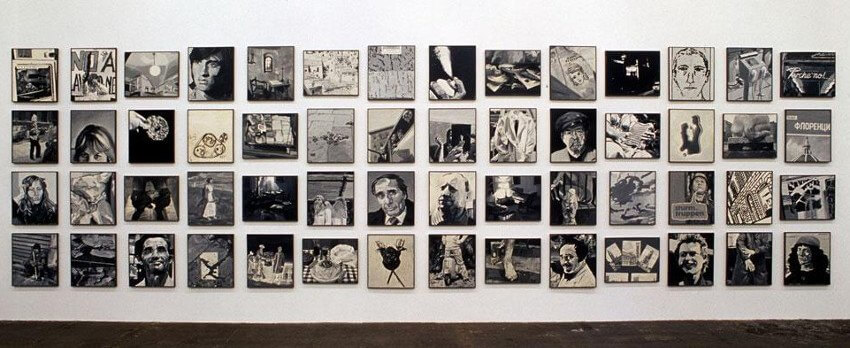

After four years in Hamburg, Kippenberger had become disenchanted with art education. He called art schools “the most stupid of all educational institutions.” He left without graduating and moved to Florence, Italy, in hopes of becoming an actor. But while in Florence he instead ended up creating what would be his first major series of paintings. Called Uno di voi, un tedesco in Firenze, the works resemble uncanny, somewhat dark souvenir postcards or holiday snaps. They are figurative, but the title, which translates into One of you, a German in Florence, offers a strange conceptual critique of the culture.

Martin Kippenberger - Uno di voi, un tedesco in Firenze, 1977. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Martin Kippenberger - Uno di voi, un tedesco in Firenze, 1977. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

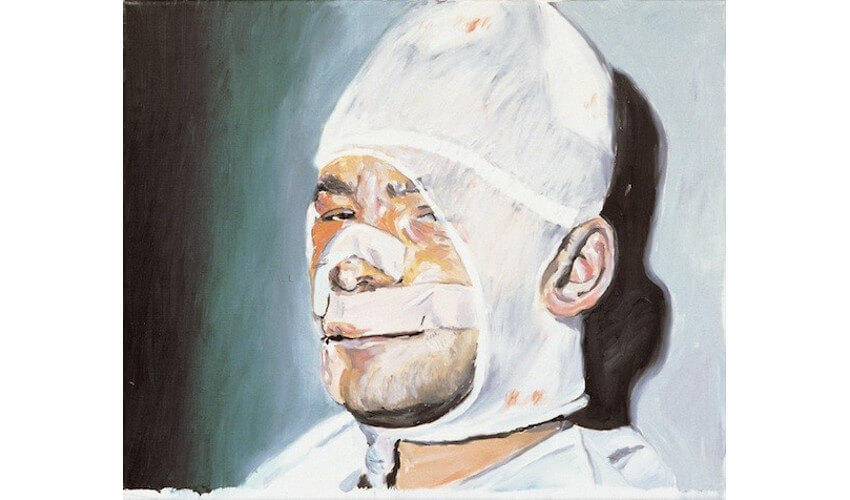

After a year in Italy, Kippenberger moved back to Germany and exhibited his Florence paintings, but German viewers considered them trivial. But having inherited money after the death of his mother, Kippenberger was free from the burden of earning a living and able to explore any artistic avenue he pleased. He purchased a stake in a famous punk rock club called S.O. 36 and started an experimental band. Then he changed the programming of the club, adding film screenings, and raised the beer prices. Some longtime customers became enraged at the changes and beat Kippenberger up one night, an event captured in his self-portrait, Dialogue with Youth. As with his Florence paintings, this self-portrait is a stoic cultural critique. Its title relates a deep cynicism toward humanity while its style embraces the Neo-Expressionist trends of the time.

Martin Kippenberger - Dialogue with Youth, 1981. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Martin Kippenberger - Dialogue with Youth, 1981. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Art vs. Life

In addition to acting, singing and managing a club, Kippenberger also spent time in Paris working on a novel, and in Los Angeles acting in films. He made sculptures, most famously creating a series of drunken lampposts inspired by his painting of a deformed lamppost for drunks, and a series of self-effacing statues titled Martin Go to the Corner and Be Ashamed of Yourself. He also experimented with furniture design, most poignantly in a work called Model Interconti, a table fashioned out of a Gerhard Richter piece he had bought. This work expresses contempt for painting while also declaring the works of other artists worthless as anything but utilitarian commodities.

Martin Kippenberger - Model Interconti. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Martin Kippenberger - Model Interconti. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

When not busy expanding his artistic practice into all available realms Kippenberger was busy making the scene, hosting parties and staying pretty much constantly drunk. His friends recall him as someone who would force everyone else to have fun, punishing them if they would not stay out with him or listen and laugh along to his long stories. Many people despised him as a sarcastic fool. But others saw him as honest and generous. His work expressed that he was confused about his own personality, and about where he fit in. It questions the nature and value of art, and the boundaries that supposedly exist between the life and work of an artist.

Martin Kippenberger - Martin Go to the Corner and Be Ashamed of Yourself. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Martin Kippenberger - Martin Go to the Corner and Be Ashamed of Yourself. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Kippenberger in America

This blurring of the boundaries between life and art manifested clearly in two experimental projects Kippenberger undertook in the Americas. The first came about in 1986, when Kippenberger purchased a gas station in Brazil and renamed it the Martin Bormann Gas Station. Martin Bormann was a prominent Nazi official who escaped capture after World War II. He was supposedly sighted around the world for decades. Nazi hunters believed he had escaped to South America. Intended as a conceptual effort, this project was misunderstood and got Kippenberger labeled as a Nazi sympathizer.

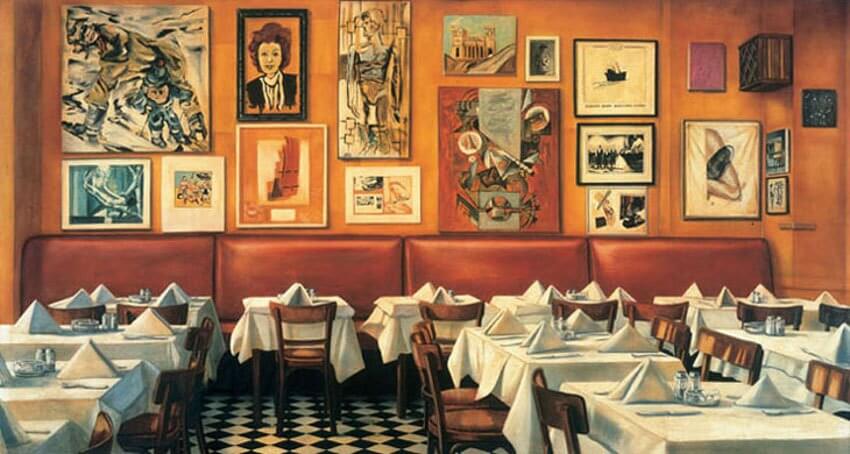

The second project was in Los Angeles, where, in 1990, he bought a 35% stake in the Capri Restaurant in Venice Beach. He routinely set himself up near the entrance of the restaurant and performed for customers. He often mocked and derided them, especially if they tried to leave during the performance. It is easy to see how both of these projects were controversial. But both can also be understood abstractly as challenges to fixed reality. The gas station transformed something mundane into something of global relevance. The restaurant project transformed a hospitality space into a space of fear. Both relate to a trend in alternate reality art projects dubbed in 1989 by Scottish artist Peter Hill as Superfictions, in which artists create real world elements of fictional narratives, blurring the line between fact and fantasy.

Martin Kippenberger - Paris Bar Berlin, 1993. Oil on Cotton. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Martin Kippenberger - Paris Bar Berlin, 1993. Oil on Cotton. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

Biography vs. Martin Kippenberger

The question we ask is whether to consider the oeuvre of Martin Kippenberger in conjunction with his biography, or to simply analyze it art qua art. Judging his work solely by aesthetics it often seems kitschy and indeed, at times, trivial. But when contemplated in conjunction with his biography it seems deeper. Kippenberger died of liver cancer caused by decades of alcohol overindulgence. But it is inaccurate to call him an alcoholic. Alcoholism implies disease or addiction—it implies remorse. Alcohol was a philosophical choice for Kippenberger. As his sister said in an interview with the Paris Review after publishing a book about the life of her brother, “he couldn’t stand other people without [alcohol]—it was too intense, you need a blur between you and them.”

Kippenberger was part of a bridge generation. The prior generation, embodied by the writer Earnest Hemmingway, believed one should have an adventurous life in order to have something authentic to say as an artist. Today people do adventurous things not in search of authenticity, but to set them apart from the competition. Martin Kippenberger was caught between the age of authenticity and the age of shallow, story-obsessed posers. Like Hemmingway, he relentlessly and extravagantly participated in his culture. Unlike Hemmingway he never felt he belonged. He was not sure whether his adventures were cultivating his art or simply exposing life as a joke. His confusion is clear in his motto, which his sister paraphrased as peinlichkeit kennt keine grenzen. It means embarrassment has no limits. In this motto, as in the work Kippenberger made, we see an abstraction; an idea about taking chances, and the value of reaching beyond what is safe.

Featured image: Martin Kippenberger - Down with Inflation (detail), 1984. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger. Represented by Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio