Mnuchin Gallery Thinks It's Time You Heard About Mary Lovelace O'Neal

Dec 18, 2019

Mnuchin Gallery in New York recently announced it will present Chasing Down the Image, a solo exhibition tracing the entire career of Mary Lovelace O’Neal, in early 2020. This is great news for fans who have been following the remarkable work O’Neal has been making for half a century. But those same fans might also be nonplussed by the language the gallery is using to promote the show. In a recent interview with artnet news, Mnuchin Gallery partner Sukanya Rajaratnam framed the exhibition as a chance to re-discover an artist who has been overlooked by history. That seems like a strange remark to make about an artist who has consistently been making and showing her art since she first enrolled in the art department at Howard University in 1960. O’Neal earned a prestigious fellowship to the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1963, and went on to earn her MFA from Columbia in New York, where she developed a distinctive visual voice that soon earned her a solo exhibition at The Museum Of Modern Art San Francisco in 1979 when she was only 37 years old. She then went on to teach in some of the most prestigious art programs in the US, including the University of Texas at Austin, the San Francisco Art Institute, and the University of California, Berkeley, where she became the first Black woman to receive tenure. All along, O'Neal has exhibited her work extensively, almost every year, including several additional solo museum exhibitions. She has also represented the United States in about half a dozen international art biennials. I first became aware of her work in 2009 while living in San Francisco. I was chastised for not knowing of her yet—she is a legend to many Californians. So while I absolutely think it is wonderful that Mnuchin is showing O’Neal, what does it mean for an artist who has been here all along to be re-discovered?

A Master of Figurative Abstraction

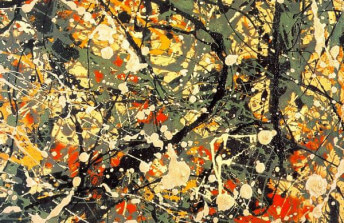

O’Neal has pointed to two major influences in her art making: Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. She appreciates the gestural, textural cacophony evoked by Abstract Expressionists like Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, noting how their methods allow the “intangible” aspects of human life to be expressed. She also admires the quietude of Minimalism, which offers a contrasting balance to her work. While at Skowhegan in the 60s, O’Neal first came into contact with a medium called lampblack—a type of carbon residue sometimes used as a paint pigment. Years later, she realized that by rubbing the raw pigment directly into the surface of a canvas she could use emotive physical gesturality—an ideal of Abstract Expressionism—to create total flatness—an ideal of Minimalism. Her “Lampblack” paintings were the first to bring her wide public attention.

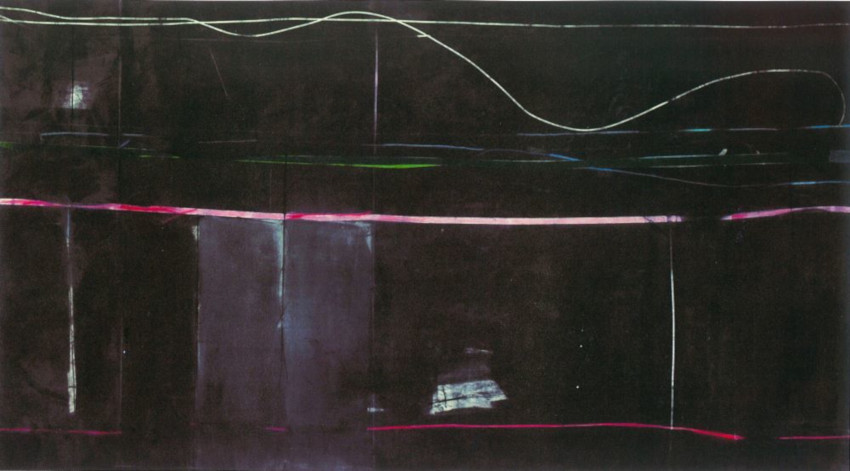

Mary Lovelace O’Neal - Black Glitter Nights, 1970s. © Mary Lovelace O’Neal. Courtesy Mnuchin Gallery, New York

Equal to her mastery of medium specificity is the profundity of her compositional instincts. Perfectly placed gestural marks and colors play off the lampblack to evoke dreamlike inner worlds where ghostly figurative impressions lurk in the abstract haze. Sparsely placed lines create innumerable zones of perception in “Black Glitter Nights” (1970s); lightness and weight push against each other in “Last Lay up” (1979); creeping fear insinuates itself upon openness and whimsy in “She thought she could fool the zebra with powder and paint” (2007). In “See, so heaven can hear you” (2007), one of her most masterful expressions of what might be described loosely as Figurative Abstraction, dancing figures seem to vibrate amid a shock of fiery red bursting forth from the blackness. What stops any of these paintings from being purely figurative is the mystery they retain. This mystery has also always been essential to O’Neal herself, who says, “If I could not be surprised by what I make, I probably would not do it.”

Mary Lovelace O’Neal - City Lights, 1988. Offset lithograph and screenprint; sheet (irregular): 28 1/8 × 32 1/8 inches. Saint Louis Art Museum, The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie. © Mary Lovelace O’Neal

The Case for Re-Discovery

Despite the fact that O’Neal has been evolving her work steadily over her entire career, and has never really stopped exhibiting, the case Rajaratnam makes that O’Neal has been neglected revolves around two points. First, O’Neal has not had a solo show in New York in 25 years. Rajaratnam offered to artnet news, “Perhaps being on the West Coast, a tenured professor, and eventual chair of the department of art at UC Berkeley had insulated [O’Neal] from the larger art world.” However, in that same 25 year time span O’Neal had solo shows in San Francisco, Oakland, New Orleans, Jackson, Mississippi, and Santiago, Chile. So what is meant by the “larger art world?” It seems to me that Rajaratnam is talking about the smaller art world: the one that embraces the outdated attitude that any city outside of New York is provincial and thus being shown in those other cities is the equivalent of being overlooked.

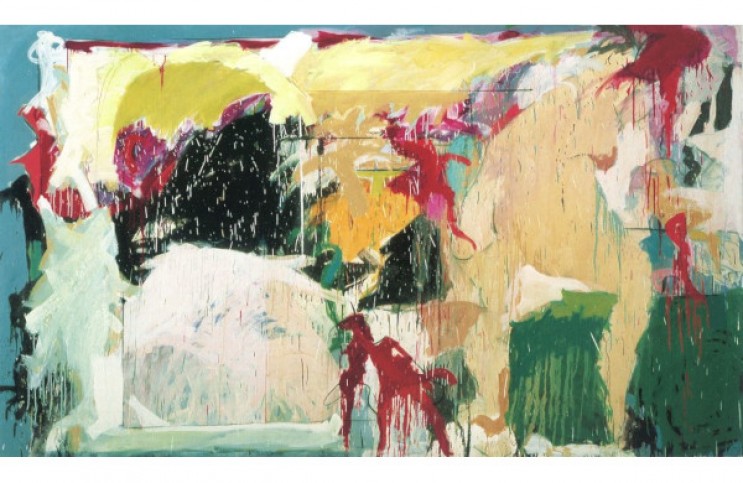

Mary Lovelace O’Neal - Running with Black Panthers and White Doves (mid-1980s/early 1990s). © Mary Lovelace O’Neal Courtesy Mnuchin Gallery, New York

The second argument Rajaratnam presents for O’Neal being overlooked relates to her not being included in the dialogue surrounding the touring exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, which has brought renewed attention to the work of many other Black American artists from the Civil Rights Era. “It is an oversight that needs to be corrected,” Rajaratnam says. This point might have merit. However, that show is the vision of one curatorial team, not official history. And all the while that show has been touring, O’Neal was included in such notable exhibitions as The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection show at the Saint Louis Art Museum, and Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today, a show entirely built around the work of Black female abstract artists that debuted at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. then traveled to the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri and the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg. Rajaratnam admits she first became aware of O’Neal in 2019, when the Baltimore Museum of Art purchased one of her paintings. However, to say an artist has been overlooked just because you personally have never heard of them dismisses the fact that tens of thousands of fans have known about and admired O’Neal for decades. There are a lot of artists working today. Most of their work will be new to most viewers. No one knows everyone. Can we find ways to celebrate the achievements of older artists who are new to us without pretending no one else has ever heard of their work?

Featured image: Mary Lovelace O’Neal - Hammem, 1984. © Mary Lovelace O’Neal. Courtesy Mnuchin Gallery, New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio