Franz Kline and His Action Painting Manner

What if all along we weren’t meant to interpret hieroglyphics? What if they weren’t symbols, but were simply aesthetic forms meant to be appreciated as art? They can certainly be appreciated as such to those of us who can’t read them anyway. The work of Franz Kline represents a moment in the evolution of Abstract Expressionism when a similar question was posed as to whether interpretation was necessary or even possible with some abstract art. Kline’s iconic gestural technique, combined with his use of common house paint brushes, resulted in brush marks that at first look right in line with those made by other Action Painters such as Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. But whereas those painters made work that was deeply rooted in underlying meaning, Kline made work that only referenced itself. The brush strokes he created were, as he explained, “unrelated to any entity but that of their own existence.”

The Search For Franz Kline

If ever there was a painter who could have devoted an entire lifetime to mining the depths of the subconscious it was Franz Kline. Kline’s early life was fraught with pain. His father died when Franz was only seven years old, and his mother soon after abandoned him to an orphanage and remarried. Later, Franz’s own wife suffered frequent bouts of mental illness and spent time in and out of mental institutions. Combined with the existential turmoil the entire world was experiencing in the 1940s, Kline’s personal struggles made him the ideal representative of the ideas about the subconscious and mystical revelation that were emerging within the Abstract Expressionist community.

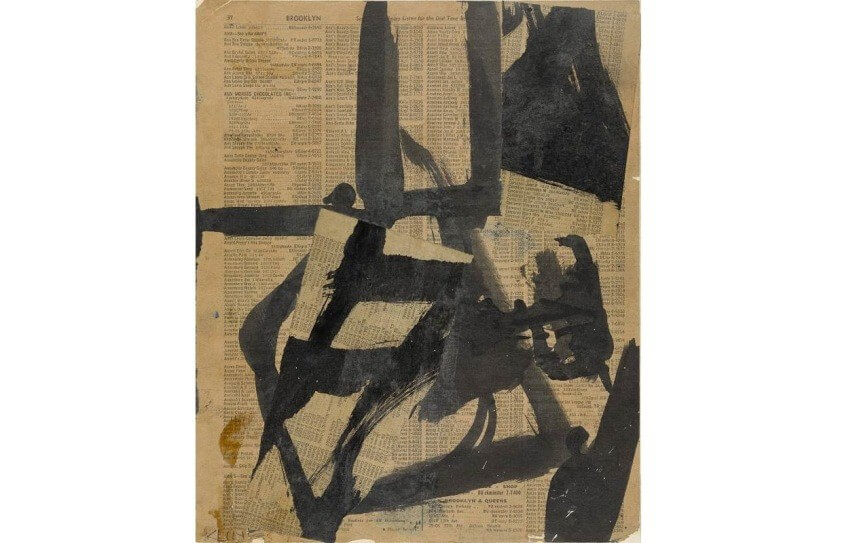

Franz Kline - Untitled II, 1952, Ink and oil on cut-and-pasted telephone book pages on paper on board, 11 x 9 in. © 2018 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

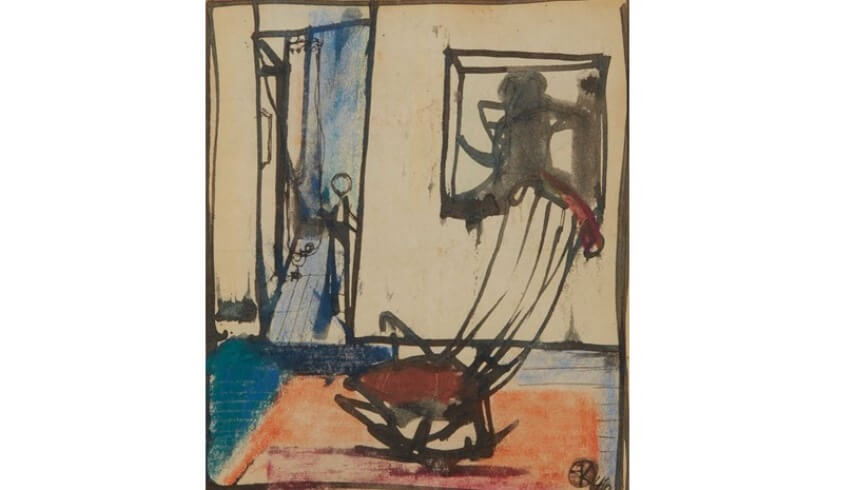

As with many of his contemporaries, Kline was originally trained as a figurative painter. His early artworks show an excellent grasp of formal technique and an advanced talent for drawing. He transitioned into abstraction after befriending members of the New York School, such as Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Hans Hoffman and Philip Guston. Through their influence, Kline narrowed his focus, exploring the nature of brush strokes in large-scale action paintings that consisted of a simplified, black and white palette. But a look at his earlier works, although figurative in nature, such as Puppet in the Paint Box, reveals some of the same brushstrokes and raw grasp of composition and color that defined the abstract style that ultimately made him famous.

Franz Kline in his studio, 1954, on the cover of LIFE Magazine with two of his iconic black and white paintings. © 2018 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Minimalist Link

Even though he was friends with, and is still today associated with the founding members of the Abstract Expressionist New York School painters, Kline’s oeuvre is different from theirs in a specific and important way. While the other Abstract Expressionists were mining their own feelings, intuitions and subconscious emotions and using them to create works that were deeply personal and rife with hidden meaning, Kline made work that was about the formal qualities of painting, such as paint, brush stroke, composition and color.

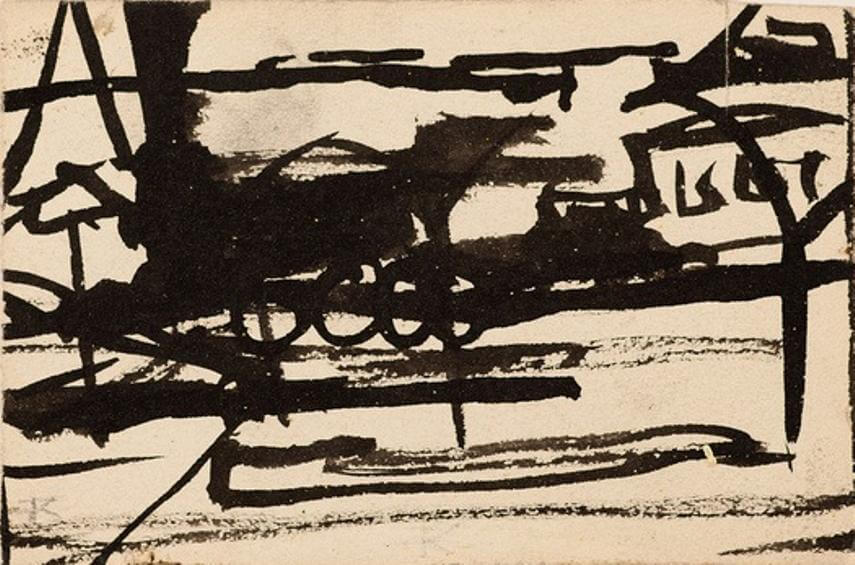

Franz Kline - Untitled – Locomotive. © 2018 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

He borrowed the gestural painting technique that had been devised by his fellow Abstract Expressionists, and with it developed his own distinct, active, physical style. But there was no mysticism or hidden meaning in Kline’s iconic action paintings. Furthermore, Kline’s painterly compositions weren’t spontaneous and instinctive like the works of Pollock, but rather were planned out ahead of time, often sketched in detail on pages of old phonebooks.

Rather than explaining or analyzing the content of his works, Kline encouraged viewers to simply interact with the marks and compositions themselves, not seeking symbolism or meaning but simply interacting with the formal qualities of the art. These works were all about the singular aesthetic appreciation of his signature brush strokes and the surrounding negative space. Kline felt that the emotional impact of the work could be experienced entirely through an appreciation of these formal qualities, and insisted that that was the most important thing on which to focus. Through this personal style he became a sort of link between the mysticism of the Abstract Expressionists and the formalism embraced by the Minimalists.

Franz Kline - Untitled – Rocking Chair. © 2018 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The de Kooning Connection

The most oft-repeated story about Kline’s evolution into an abstract master is this one: He was already making gestural action paintings, albeit on a small scale. These pieces, such as Untitled – Locomotive, and Untitled – Rocking Chair, both from 1946, contain all of the raw materials of stroke, line, color and composition that would eventually define his later style. According to legend, Kline’s friend Willem de Kooning encouraged Kline to project these small paintings largely onto the wall, so enlarged that he could simply appreciate the individual brush strokes on their own.

Franz Kline - Chief, 1950, Oil on canvas, 58 3/8 x 73 ½ in. © 2018 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As with all stories from the art world, this one has its nay-sayers. Whether it’s a myth based in fact or not, however, is irrelevant. It is evident from his work in the late 1940s that Kline had already been moving in the direction of isolating the formal nature and features of his brush marks. Whether it was de Kooning who recommended that he work large, bringing the brush strokes into monumental focus, or he came up with the idea himself doesn’t make much difference. Either way, by 1950 he had fully embraced the idea of working large. That year he received his first solo exhibition at New York’s Charles Egan Gallery, which introduced him and his large-scale brush stroke paintings, such as Chief, to America.

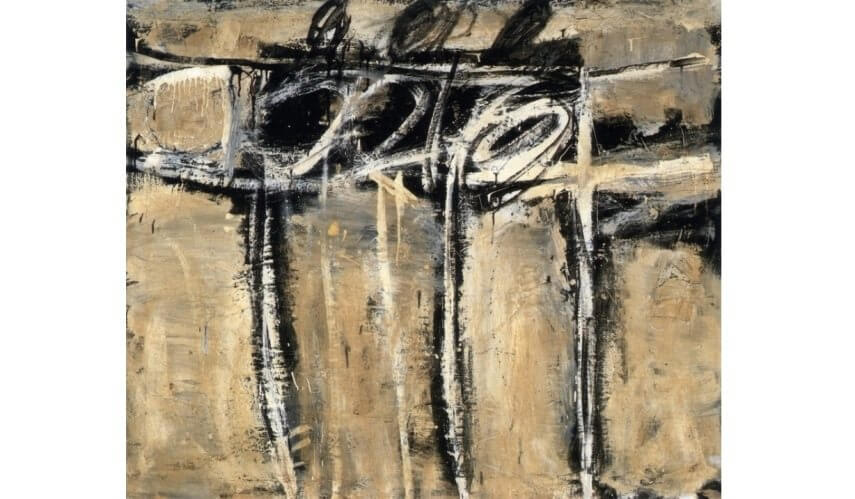

Cy Twombly - Untitled, 1951, Industrial paint on canvas, 85 x 101 cm. © 2018 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Franz Kline the Teacher

Throughout the 1950s Kline became more famous and more influential. He taught at several different institutions during this time, including the Black Mountain College and Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute. What is most evident in the work of his students is their willingness to explore their own relationship to gesture, mark making and physicality. One of Kline’s most famous students was the abstract painter Cy Twombly, who studied under Kline in 1951 at Black Mountain. Twombly’s own iconic style is a highly individual form of action painting profoundly influenced by Kline’s technique.

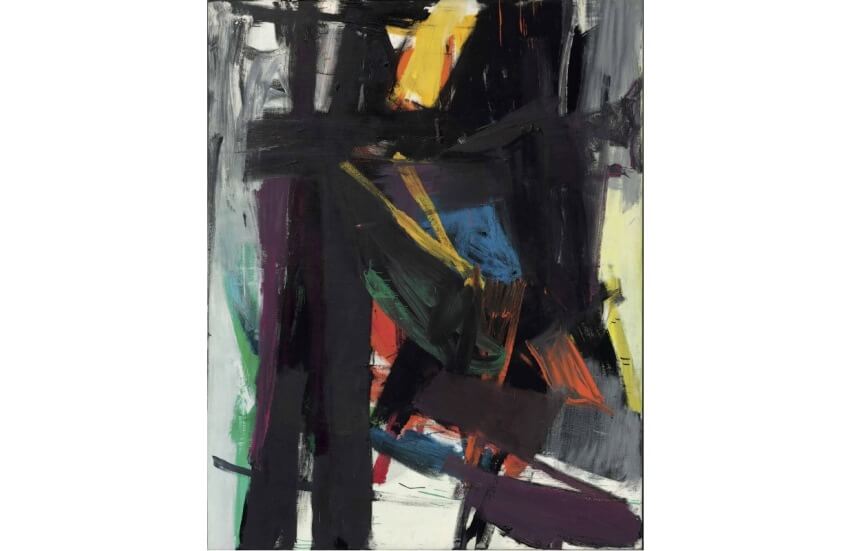

Franz Kline - King Oliver, 1958, Oil on canvas, 251.4 x 196.8 cm. © 2018 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the late 1950s, Kline expanded his style to include a wider color palette. In pieces such as King Oliver, painted in 1958, his iconic personal style is still evident, as are his gestural brush strokes. But the increased color palette adds new dimensions to the work that draw attention away from the qualities of the marks and into a deeper examination of the other formal qualities of the painting. Kline achieved international notoriety in this period of his life thanks to his work being included in a traveling exhibition staged by New York’s MoMA called The New American Painting, which toured Europe in 1958.

Franz Kline died suddenly in 1962 of heart failure. Though he never lived to see the full blossoming of movements such as Minimalism and Post-Painterly Abstraction, his focus on the formal qualities of Abstract Expressionist mark making definitely led to their intellectual development and their critical success. Through Kline’s iconic artworks, we see a conceptual bridge take place. His work as an artist and an educator encouraged many in his own generation and future generations to consider paintings as objects rather than mediums or intermediaries to transcendent experiences, and assisted late 20th Century Modernism in its quest to stay inventive and free.

Featured Image: Franz Kline - Puppet in the Paint Box, 1940, Oil on canvas board, 14 x 18 in.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio