How Action Painting Changed Art

Aug 29, 2016

If the phrase “action painting” sounds confusing, that could be because it seems to contain a redundancy. Painting implies action. Can there be inaction paintings? But neither the fact that painting is an action nor that paintings result from action have much to do with the action painting definition. In fact action painting isn’t really about action or painting at all. It is about a state of mind. The art critic Harold Rosenberg coined the phrase action painting in 1952, in an essay titled “The American Action Painters.” The essay was an attempt to explain what Rosenberg considered to be a fundamental shift occurring in the mindset of a small group of American abstract painters. Rather than approaching painting as image making, these painters were using the act of painting to record the results of personal, intuitive, subconscious dramas they were acting out in front of the canvas. They were using the canvas as a stage. They were actors, and the paint was the method of recording the evidence of the event. In his essay, Rosenberg not only pointed out the newness of this method, but he also entirely shifted the attention away from paintings as objects, declaring that all that mattered to action painters was the creative act.

The End of Objectness

Prior to Rosenberg’s observation, no respected art critic had ever suggested in writing that the point of an artist’s work wasn’t to create something tangible. It was taken for granted that the purpose of being an artist was to create works of art. But what Rosenberg observed about painters like Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning was that they were not focused on creating objects. Rather they were focused on their own process as painters. They were placing the utmost importance not on the finished product, but on the act of connecting to their own unconscious. The painting was simply a way for them to record the resulting effects of that connection.

Imagine being blindfolded and given a paintbrush then being told to find your way through a maze while running the paintbrush along the surface of the wall. The resulting mark left on the wall would not be an aesthetic achievement so much as it would be a record of your journey. Such was the root of Rosenberg’s observation: that the action painters were not making images; they were making outward recordings of their inward journeys.

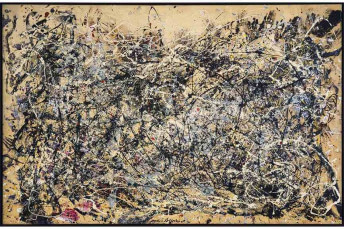

Jackson Pollock - Number 8, 1949, 1949. Oil, enamel, and aluminum paint on canvas. 34 × 71 1/2 in; 86.4 × 181.6 cm. American Federation of Arts. © 2020 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Action Painting Techniques

When a painter sets out to make a painting of a specific image, the tools and techniques involved need to offer the painter as much control as possible. But if the point of a painting is not to make a specific, pre-determined image, but is rather to create an abstract visual relic of a psycho-physical event, the painter can enjoy more flexibility in terms of tools and techniques. Since action painting is about spontaneity and being able to seamlessly convey every subconscious intuition through a physical gesture, anything that hinders freedom and instinct must be abandoned.

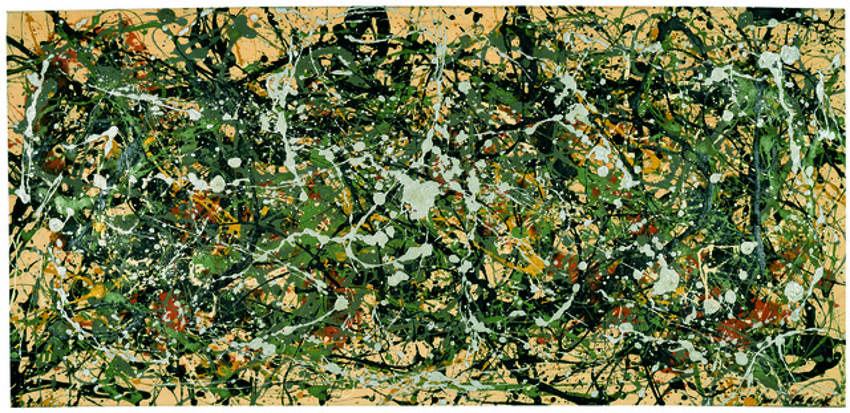

The action painter Jackson Pollock abandoned traditional preparations and supports and instead painted directly onto unprimed canvases laid out on the floor. He forewent traditional tools opting instead to apply paint to his surfaces using whatever he happened to have, including house painting brushes, sticks or even bare hands. He often flung, poured, splashed and dripped paint onto his surfaces directly from whatever container the paint was in. And he used whatever medium was handy, including all manners of liquid paint, as well as broken glass, cigarette butts, rubber bands and whatever else his instinct commanded.

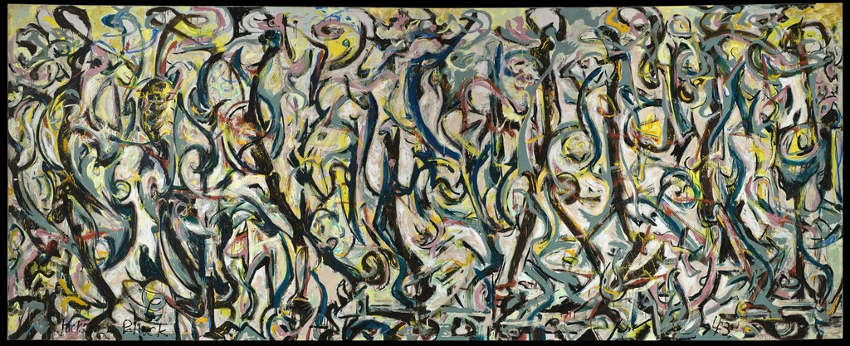

Jackson Pollock - Mural, 1943. Oil and casein on canvas. 95 7/10 × 237 1/2 in; 243.2 × 603.2 cm. Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Bilbao

Grand Gestures

In addition to being free with mediums, tools and techniques, the action painters also released themselves from the constraints of their own physicality. Franz Kline’s action paintings are all about physical gesture. Each bold mark Kline made on the canvas is a record of a moment when his body was fully engaged in motion. Whereas an Impressionist brushstroke is made something so subtle as the flick of a wrist, Kline’s brushstrokes were made by a thrust of his whole arm, or his entire body, as guided by the inner reaches of his mind.

Pollock often made no contact with the canvas at all. Instead he relied on momentum and the dynamic use of his body, creating speed and power to project the medium into space and onto the surface. By not hindering his motion by contact with the surface he was collaborating with the powers of nature, which resulted in free-flowing, elegant and organic-looking marks. In a sense, Pollock and Kline’s gestures were not only creating marks, they were making impacts. Like meteor craters, these impacts can be appreciated both for their appearance and also for the primal, ancient, natural forces that caused them.

Franz Kline - Mahoning, 1956. Oil and paper collage on canvas, 80 × 100 in. (203.2 × 254 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art 57.10. © 2020 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Conscientious Unconscious

The rise of action painting was not a mystery. It had logical roots in the context of post-World War II American culture. American society at large was recovering from war and adjusting to a strange new modern reality. In their efforts to understand themselves and their world, people became increasingly interested in psychology, especially ideas surrounding subconscious and unconscious thoughts. In the minds of the American action painters, these ideas tied in directly with the work the Surrealists had done with automatic drawing, which involved letting the body create marks based on reflexive movements inspired by unconscious impulses.

Their thinking also tied in with primitive traditions found in the totemic artwork of Northern American native cultures. Totemic art is tied in with a belief that people are connected to each other, to history and to the natural and spiritual worlds through certain natural objects, or through beings that possess spiritual or mystical powers. The action painters hoped that through their intuitive, subconscious painting style they could channel totemic imagery that viewers could connect with in the presence of the aesthetic relics of their process.

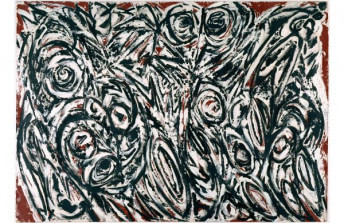

Jaanika Peerna - Small Maelstrom (Ref 855), 2009. Pigment pencil on mylar. 45.8 x 45.8 cm

Action Painting’s Legacy

The preciousness of the gift that action painting gave to future generations of artists cannot be overstated. Harold Rosenberg’s thoughtfully stated observations inspired a tremendous change in Modernist art. He gave words to the thought that process is more important than product. He proved that the journey really is more important than the destination, or if that sounds too cliché, he proved that the drama that unfolds during the process of a painter’s creative act is more important than the relic that results from that process.

Rosenberg’s realization freed ensuing generations of artists from thinking about their work solely in terms of “product making.” They could engage in experimental processes and focus fully on ideas. They had permission to begin without having to predict the end results. Without this shift in the consciousness of artists, we never would have been able to enjoy “happenings” or the work of conceptual artists or the Fluxus movement. We never would have been able to experience the ephemeral, transient mysteries of land art. We never would have enjoyed the fruits of the alternative art space movement. In so many ways, it was action painting that enabled artists to shift their focus away from where exactly they were going, and to remind themselves that often the most important thing in art and in life is how they get there.

Featured Image: Jackson Pollock - Greyed Rainbow, 1953. Oil on linen. 72 × 96 1/10 in; 182.9 × 244.2 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. © 2020 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio