Centre Pompidou Celebrates Henri Matisse’s 150th Birthday

In 1971, the French poet Louis Aragon published an unprecedented work of literature titled Henri Matisse, which Aragon described as a novel. It more closely resembles a loose amalgam of memoir, poetry, pontifications, sketches, and records of happily rambling conversations Aragon had with his friend Henri Matisse during the last 13 years of his life. The monumental tome—it spans two hard cover volumes and amounts to more than 700 pages—took Aragon 27 years to complete. “This book is like nothing but its own chaos,” Aragon writes. “It straggles over twenty-seven years…a trail of scattered pins from an overturned box.” His goal was not to write a biography of Matisse, nor to offer a critique, nor even a description, of his art. The only thing Aragon wanted to accomplish with his book was to “sound a kind of calm, distant echo of a man.” I have been slowly combing through my own copy of this book for years, reading and re-reading small sections at a time. Now, I have the perfect excuse to finish it. This October (assuming the COVID-19 pandemic subsides and museums once again open to the public), Centre Pompidou will present Matisse: Like a Novel—a retrospective inspired by the Aragon novel. The exhibition was timed to celebrate the 150th birthday of the artist, which technically already passed on 31 December 2019, but any excuse is good enough to spend a few hours with Matisse. The selection of works on view promises to be extraordinary. In addition to rarely exhibited works from numerous international and private collections, it will include paintings from the collections of four French Museums: the National Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Grenoble, and the two French Matisse museums (one in Cateau-Cambrésis, and one in Nice). Most importantly, it will include an ample selection of writings by Matisse, spanning his entire career. Seeing this many Matisse works accompanied by his own insights and recollections promises to add something tactile to what Aragon started, enabling viewers to personally grasp what Aragon called “the expression of himself that [Matisse] wanted to leave behind.”

Painting Himself

Prior to encountering the Aragon novel, I had my own distinct idea about who, or what, Matisse was. I saw him as a compulsively creative tactician: someone who could not live without making art, and who would die of boredom unless he kept on innovating. He seemed to me to be someone who wanted very much to be on the forefront of Modernity, an urge spurred on, perhaps, as much by ego as anything else. He was one of the few artists I knew of who definitively made the effort to start trends rather than follow them, and who continually re-invented his own visual language. I was impressed by the few of his paintings that I had seen in person, but had to admit that I felt precious little heart coming from them. I enjoyed, but had trouble formulating a personal connection with, the work.

Henri Matisse - Autoportrait, 1906. Huile sur toile, 55 × 46 cm. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhague. © Succession H. Matisse. Photo © SMK Photo/Jakob Skou-Hansen

Aragon helped me see the human side of Matisse. The poet first met Matisse during World War II. A communist and active member of the French resistance to the German occupation of France, Aragon fled to Nice with his wife, the Russian author Elsa Triolet. Matisse lived nearby, so Aragon introduced himself and the two became friends. He would hang out in the studio while Matisse worked, and socialize with him outside of work. Their conversations and letters reveal an intellectual, even spiritual, bond. I always knew Matisse was concerned with painting modernity, but through his insightful writings, Aragon helped me finally to grasp the simple truth that had eluded me: Matisse was not painting modernity, he was painting Matisse. “Every canvas,” writes Aragon, “every sheet of paper over which his charcoal, his pencil, or his pen wandered, is Matisse’s utterance about himself.” Modernity was just an essential part of who and what Matisse was.

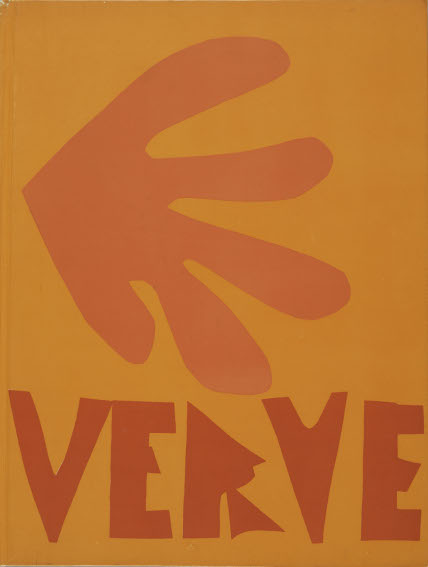

Henri Matisse - Verve, n°35-36, 1958. Revue 36,5 × 26,5 cm (fermé). Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris. © Succession H. Matisse. Photo © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky / Dist. Rmn-Gp

The Search For Newness

Glancing through the myriad works included in Matisse: Like a Novel it becomes immediately apparent that the search for newness was essential for Matisse. He worked his way through at least half a dozen distinct stylistic changes throughout his career. One quote from 1942 hints that this was an intentional pursuit connected to what Matisse hoped would be his legacy: “The importance of an artist,” he wrote, “is measured by the quantity of new signs that he will have introduced into plastic language.” What may be less understood is just how laborious Matisse found the search for newness to be. In 2010, The Art Institute of Chicago and MoMA teamed up on a retrospective called Matisse: Radical Invention (1913 – 1917). In the years leading up to the exhibition, conservators made a fresh analysis of the Matisse painting Bathers by a River (1909, 10, 13, 16, 17). The unusual date gives some hint to what they found when they analyzed large-scale, seamless x-rays of the work.

Henri Matisse - Les Tapis rouges, 1906. Huile sur toile, 86 × 116 cm. Musée de Grenoble. © Succession H. Matisse. Photo © Ville de Grenoble/Musée de Grenoble- J.L. Lacroix

Matisse had painted, completely scraped off, re-drawn and re-painted the composition repeatedly over the course of nearly a decade. Each new version included new colors, new textures, new forms, new lines and a new composition. Matisse referred to this process as part of his attempt to understand “the methods of Modern construction.” He also used to study and copy the works of Old Masters, and even the works of his contemporaries, rearranging their elements in an effort to discover specifically makes a painting “Modern.” Reading his own words today as we look through his various evolutions, we are confronted with how introspectively he approached his process. What seem at first like radical jumps forward actually occurred slowly over the course of many years. Matisse had the unique sensibilities to find newness even in the most unexpected places; even in oldness. His writings show just how hard he worked to nurture these sensibilities, and prove how difficult, and extraordinary, his achievements were.

Featured image: Henri Matisse - La Tristesse du roi, 1952. Papiers gouachés, découpés, collés et marouflés sur toile. 292 × 386 cm. Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris. © Succession H. Matisse. Photo © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci/Philippe Migeat/Dist. Rmn-Gp

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio