How Natalia Goncharova Shaped Russian Futurism

Natalia Goncharova has not yet gotten her due. As a young painter she was a monumental force in the Russian avant-garde, working and exhibiting alongside some of the most important names in early abstraction, like Kazimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky. But when she died in 1962, Goncharova was broke, and was soon forgotten by most art historians and collectors in the West. That is until 2007, when Goncharova vaulted to the forefront of the art world when her painting Picking Apples (1909) sold at auction for $9.8 million (US), a then record-setting price for a female artist. Georgia O’Keeffe now holds that record for her Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 (1932), which sold in 2014 for $44.4 million. But Natalia Goncharova is still firmly on the list of the top five, along with Louis Bourgeois, Joan Mitchell and Berthe Morisot. But that single fact, sadly, is almost all contemporary collectors know about this unique artist. And were it not for the relatively recent influx of Russian wealth to the art market, most would not even know that. What has yet to be adequately expressed is the integral role Natalia Goncharova played in the aesthetic history of Modernism. She did not have a single, straightforward style that could have allowed her to be as easily remembered as her contemporaries, but more than anyone else of her generation she intuitively grasped the complex relationship that exists between Primitivism and Modernism: a relationship that helped shape not only Russian Futurism, but all of modern and contemporary abstract art.

The Birth of Russian Modernism

Natalia Goncharova was born in Tula Oblast, western Russia, in 1881. Her father was an architect and an art school graduate. In 1901, when Natalia decided she, too, wanted to be an artist, she entered the same school as her father, the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. She studied there for nearly a decade, beginning as a sculptor but soon moving into painting where she found it easier to explore color in innovative ways. It was a time of cultural change in Russia. The art movement Mir iskusstva, or World of Art, was pressuring the academic class to reject traditional realism in favor of more experimental, individualistic artistic voices. Goncharova was on their side, but her taste for innovation was not shared by most of her teachers.

Happily for her, one of her teachers, the sculptor Paolo Petrovich Troubetzkoy, a key member of the World of Art movement, encouraged her. But despite his help Goncharova felt unappreciated and unenthused, and in 1909 dropped out. The following year, the smoldering disagreement at the school between those beholden to the past and those longing for newness came to a head, and several progressive students were expelled for their aesthetic positions. In response, Natalia, her lover (and eventual husband) Mikhail Larionov, along with several of the expelled students formed an outsider artist group called Knave of Diamonds. At first they imitated trends in European Modernism. But with Goncharova at the lead they quickly grew beyond imitation in an effort to discover what authentic Russian Modernism could be.

Natalia Goncharova - Flowers, 1912 (left) and Natalia Goncharova - Rayonist Lilies, 1913 (right)

Natalia Goncharova - Flowers, 1912 (left) and Natalia Goncharova - Rayonist Lilies, 1913 (right)

Approved by Natalia Goncharova

Over the next few years, Goncharova rapidly evolved her aesthetic point of view, rejecting all authorities on art except herself. She explored primitivism simultaneously with the emerging trend of Futurism. On the one hand she found inspiration in the color relationships and subject matter connected with Russian folk art. On the other hand she was fascinated by the Cubist search for hyperspace, or a dimension beyond the third; the Rayonist notion that speed is best expressed visually by hard, diagonal lines; and the Fauvist use of vivid, unrealistic colors inspired by French artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne.

Over the course of just a few years Goncharova combined all of these points of view to create a unique, purely Russian aesthetic position that was on the cutting edge of Modernism. In the process she joined several of the most influential avant-garde art groups in Russia and Europe. She was an original member of The Blue Rider, founded by Wassily Kandinsky. She exhibited more than 50 paintings in The Donkey’s Tail exhibition of 1912, along with the painters Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall. (Russian officials confiscated several of her works from that exhibition for being obscene.) And that same year she also became a founding member of the Russian Futurists.

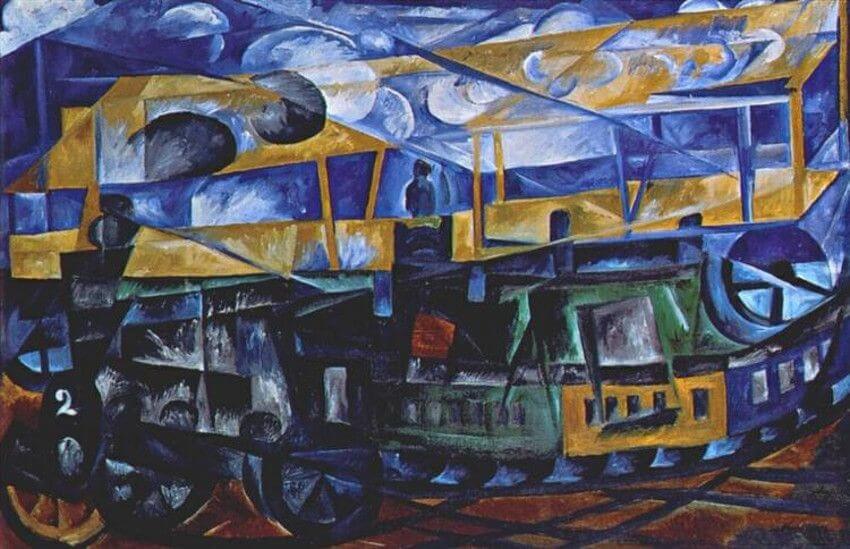

Natalia Goncharova - Airplane over Train, 1913

Natalia Goncharova - Airplane over Train, 1913

The Present Never Lasts

The genius of what Natalia Goncharova accomplished came from her instinctive realization that nothing stays the same. She embraced the past while also striving always for what could be next. Like her Futurist contemporaries, she rejected tradition because she saw that as soon as a tradition is established it represents death. Everything is either moving forward or backward; nothing stands still. And we can see this tireless longing for the future in the myriad changes she explored to her style over the decades. We can also see it in the multi-disciplinary approach she took to her art, exploring sculpture, painting, fashion, graphic design, typography, illustration, literature and set design.

So many other avant-garde artists of her generation wanted only to destroy the past in its entirety. But while Goncharova agreed that most modern institutions were useless, she respected the most primitive aspects of Russian culture and embraced them, because she understood that those are the deep roots that defined who she was. Later, when movements like Art Brut and Abstract Expressionism professed to innovate this connection between the distant past and the present moment, they owed a debt to Natalia Goncharova: one of the first Modernists to firmly connect the primitive with the modern, and to allow the invisible, resonant chord that connects the two to inform her work.

Natalia Goncharova - Still Life With Ham, 1912 (left) and Natalia Goncharova - Yellow And Green Forest, 1913 (right)

Natalia Goncharova - Still Life With Ham, 1912 (left) and Natalia Goncharova - Yellow And Green Forest, 1913 (right)

Featured image: Natalia Goncharova - Forest (Red-green), 1913-1914

By Phillip Barcio