Norman Lewis, a Neglected Gem of Abstract Expressionism

When the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts mounted “Procession: The Art of Norman Lewis” in 2015, the exhibition was a revelation to most viewers. The subject of the show, the American painter Norman Wilfred Lewis (1909 – 1979), is considered to have been the only Black artist amongst the first generation of Abstract Expressionists. His work is completely distinctive from that of his peers, following aesthetic and intellectual threads that endow it with a sense of freshness and ingenuity even today. Yet unlike Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and the other painters with whom he often exhibited, Lewis never achieved great fame or financial success in his lifetime. He mostly supported himself and his family as a teacher. One of the key reasons he struggled in the marketplace was that despite the way the white, Post War, American art establishment embraced abstract art, it nonetheless mostly dismissed the work of Black artists, abstract or not. At the same time, most Post War Black American art dealers and collectors also dismissed abstract art because of a belief that social justice could only be achieved by art that directly addressed issues of social justice. In fact, when he began his career in the 1930s, Lewis himself had that same belief. He painted figurative, social realist paintings as part of the Works Progress Administration, a job at which he met fellow Abstract Expressionist Pollock. But during World War II, Lewis could not help but note the hypocrisy of the American army fighting a White Supremacist enemy while simultaneously forcing the racial segregation of its own troops. After the war, Lewis abandoned his belief that realistic art could ever play a significant role in reshaping the culture. He said, “I used to paint Negroes being dispossessed; discrimination, and slowly I became aware of the fact that this didn't move anybody, it didn't make things better.” He dedicated himself instead to a lifelong exploration of the more universal aspects of aesthetics, mobilizing the power of color, line, texture, and form to bring people together in a visual space of contemplation and transcendence.

Engaging Line and Space

One of the most distinctive aspects of the abstract painting style that Lewis developed is his use of line. His brush strokes are wispy and energetic, even lyrical, and yet they possess an architectonic structure that endows them with a sense of strength and weight. He employed this element in such a way that his lines created relationships with each other, implying the presence of forms rather than describing literal objects in space. In paintings like “Street Musicians” (1948), a congregation of lines occupies the center ground of the canvas, surrounded by a pinkish, atmospheric haze. The painting is fully abstract, and yet because of the way the space is divided it seems as though it is a picture of something recognizable. The linear patterns in the middle of the canvas suggest the appearance of actual musicians, perhaps shattered into a Cubist multi-verse of perspectives and planes. But this is not a picture of musicians. This is more of an expression of the the energy and emotion of music played on the street; the excitement of notes piercing space, and the carnival of colors and sounds as they fill the air.

Norman Lewis - Florence, 1947. Oil on Masonite. 14 x 18 in. Private collection. © The Estate of Norman W. Lewis, Courtesy of Iandor Fine Arts, New Jersey.

In addition to his use of line, Lewis also developed a distinctive and highly effective method of engaging with visual space. His were not “all-over” paintings like the paintings of Jackson Pollock, covering every inch of the canvas with brush marks in such a way that no part of the canvas deserved more attention than any other part. Rather, Lewis gave viewers something to focus on within the pictorial space, even if the subject of their focus was abstract. In “Green Mist” (1948), he achieved this by blending techniques in such a way that the eye was intuitively drawn to the center of the canvas. On the outer edge of the canvas, the paint is smudged and smoothed by hand to create the sensation of an atmospheric green cloud, while in the center of the image, crisp, calligraphic lines suggest that something concrete is present, or perhaps evolving within the mystery of the visual space.

Norman Lewis - Crossing, 1948. Oil on canvas. 25 x 54 in. Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. © The Estate of Norman W. Lewis, Courtesy of Iandor Fine Arts, New Jersey.

The Spiral Group

Although his decision to explore the universal aspects of aesthetics rather than realistic portrayals of the Black struggle in America did little to raise his profile amongst dealers or collectors, it did bring Lewis into the company of other Black American artists who shared his belief in the importance of aesthetic achievement. On 5 July 1963, he was invited to the studio of Romare Bearden to join Hale Woodruff, Charles Alston, James Yeargans, Felrath Hines, Richard Mayhew and William Pritchard to form a collective known as The Spiral Group. The group was dedicated to promoting aesthetic mastery and cultural universalities. They met regularly to discus the ways realistic depictions of racial inequality did or did not help Black Culture, and to study how excellence in the realm of “common aesthetic problems” might do more to raise the cultural status and increase the influence of Black artists in America.

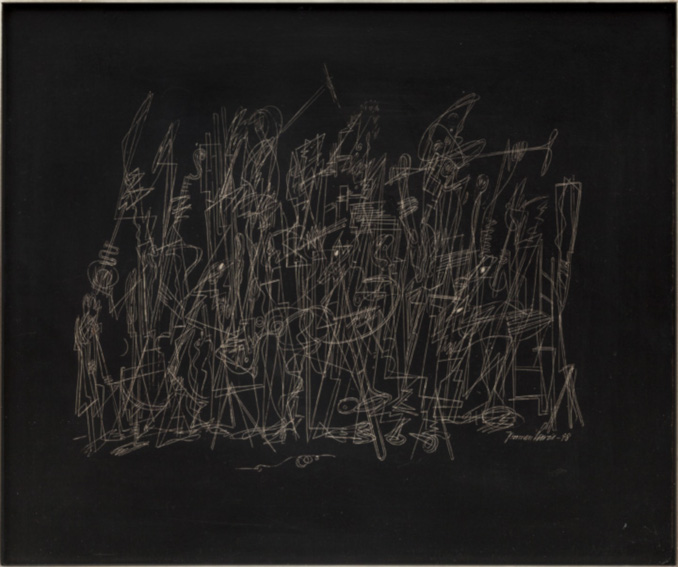

Norman Lewis - Jazz Band, 1948. Incised on black coated masonite board. 20 x 23 7/8 in. Private collection. © The Estate of Norman W. Lewis, Courtesy of Iandor Fine Arts, New Jersey

The name Spiral Group was suggested by Hale Woodruff. It was a reference to the Greek mathematician Archimedes, whose “screw” spiraled “upward in ever broader circles, as its symbol of progress.” Although some of the painters in The Spiral Group made figurative work, their wholehearted embrace of the potentialities of abstraction was groundbreaking, especially for Black American art. It laid the groundwork for artists like sculptor Richard Hunt, whose solo exhibition in 1971 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York was only the third solo exhibition by a Black artist in the history of MoMA, and the first by an abstract artist. It also brought into sharp focus the unfortunate reality that in America there never has been only one art world, but multiple art worlds competing for recognition and influence rather than cooperating towards common cultural goals. Norman Lewis and the other members of The Spiral Group laid the groundwork for something better: an approach to art that is not only universal, but unifying.

Click here to read more about this artist who became a voice in Abstract Expressionism.

Featured image: Norman Lewis - Untitled, 1949. Oil on canvas. 20 x 30 in. Private collection. © The Estate of Norman W. Lewis, Courtesy of Iandor Fine Arts, New Jersey.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio